author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Allowing AI to drive information gathering, analysis, and even creativity can be very helpful, but without a heavy human hand on the wheel, is society on a collision course to moral collapse? Avoiding such an outcome will involve many intentional actions; a main one must be asking the right questions.

People sometimes ask me the question, “Did you always want to be a teacher/professor?” My answer is easy, “Absolutely not.” For most of my early life I was terrified of public speaking.

However, I’ve always had one trait that serves educators well – curiosity. Even at a young age, I was very inquisitive, often wanting to know how and why. I remember one day, when I was four or five my loving mother, fatigued by all my inquiries, exclaimed with some exacerbation, “David, you ask so many questions!”

Curiosity has served me well in business roles and in higher education, where I tell my students asking good questions is one of the best skills they can develop. Among other things, the right questions clarify needs and spur creative solutions. Questions are also critical for challenging potential immorality.

Effective use of AI often depends on a person’s ability to ask the right question of the appropriate app. Those inquiries can involve literal questions, e.g., asking ChatGPT, “Who is the best target market for gardening tools?” Questions also can be framed as commands, e.g., if someone wants to know what an eye-catching image for a gardening blog might be, they ask Midjourney to complete a specific task, “Create an image about gardening tomatoes.”

It was a question I heard while watching Bloomberg business one February many years ago that helped inspire me to write about ethical issues in marketing. As the two program anchors bantered about the recent Super Bowl, they asked each other, “Which commercial did you like best?” Each answered, “the one with the little blue pill,” which both thought was for Viagra. Unfortunately, their recall wasn’t close; it was a Fiat ad.

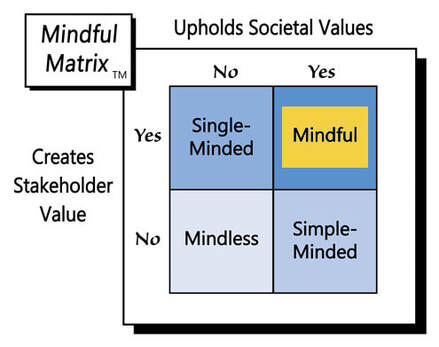

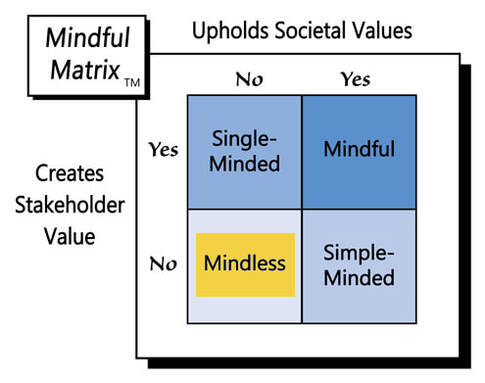

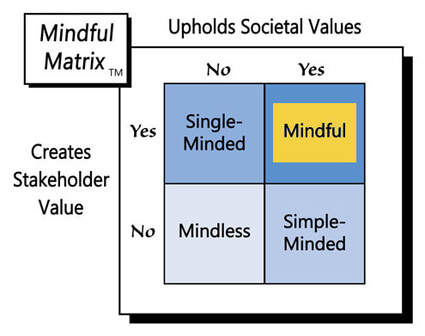

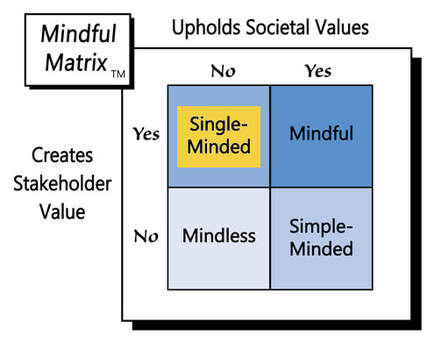

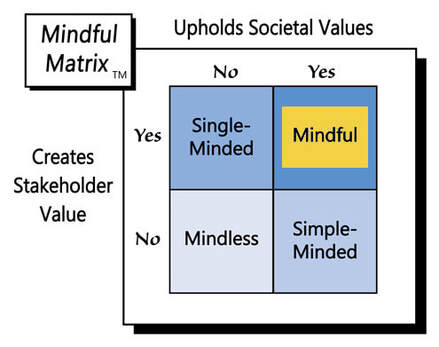

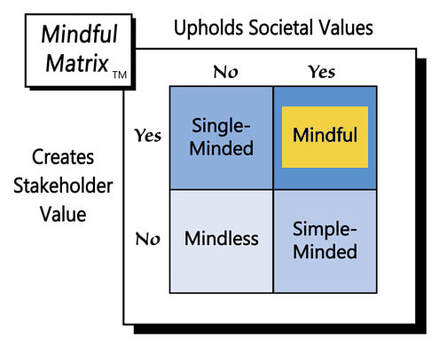

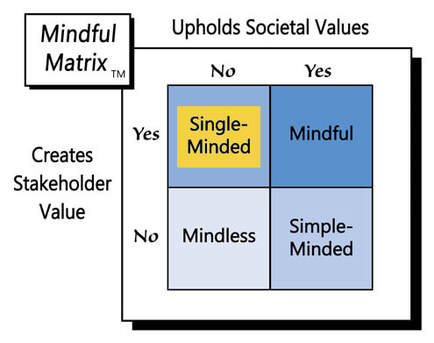

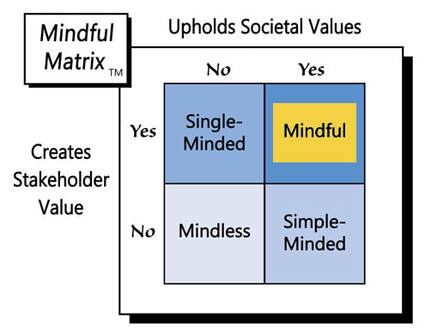

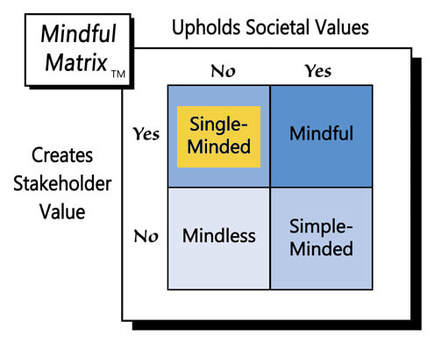

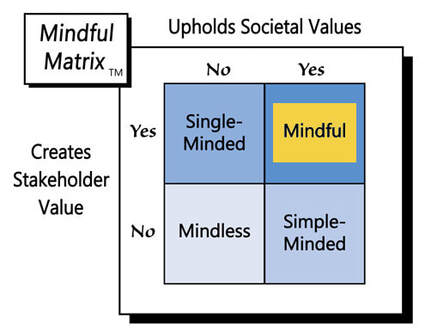

If a company spends $7 million on 30 seconds of airtime, they should want to know: “Was the ad effective?” Also, given that 123.7 million people, or more than a third of the U.S. population, ranging from four-year-olds to ninety-four-year-olds, watched the last Super Bowl, everyone should be asking, “Are the ads ethical?” Those two questions create the four quadrants of the Mindful Matrix, a tool that many have used to frame moral questions in the field.

It’s been almost seven years since I first asked questions about the ethics of AI. Business Insider published the article in which I posed four questions about artificial intelligence:

- Whose moral standards should be used?

- Can machines converse about moral issues?

- Can algorithms take context into account?

- Who should be accountable?

I didn’t know very much about AI then, and I’m still learning, but as I look back at the questions now, it seems they’ve aged pretty well. Those four queries have led me to ask many more AI-related ethics questions, which I’ve posed in nearly a dozen Mindful Marketing articles over recent years, for instance:

- Is TikTok’s AI-driven app addictive?

- How can people keep their jobs safe from AI?

- Should organizations use artificial endorsers?

- What should marketers do about deepfakes?

- Should businesses slow AI innovation?

I’ve also gone directly to the source and asked AI questions about AI ethics. More than once, I spent hours peppering ChatGPT with ethics-related inquiries. During one lengthy conversation the chatbot conceded that “AI alone should not be relied upon to make ethical decisions” and that “AI does not have the ability to understand complex moral and ethical issues that arise in decision-making.”

ChatGPT’s self-awareness proved accurate when just a few weeks later I again engaged in an extended conversation with the chatbot, asking it to create text for a sponsored post about paper towels for Facebook and to make it look like an ordinary person’s post rather than an ad. My request to create a native ad would give many marketers moral pause, but the chatbot didn’t blink; instead, it readily obliged with some enticing and deceptive copy.

These experiences have led me to wonder:

Even if AI is able to answer some ethical questions, who will ask ethical questions?

Over the years, many people have asked me questions about ethical issues. A few months ago, I wrote about an undergraduate student of mine, “Grant,” who asked me about an ethical issue in his internship. His company wanted to create fake customers who could pose questions related to products it wanted to promote.

On the other end of the higher ed spectrum, I recently served on the dissertation committee of a doctoral student who asked me to help her answer a question related to my earlier exchange with ChatGPT, “Does recognition matter in evaluating the ethics of native advertising?” Turns out, it does.

Business practitioners also have often asked me about ethical issues. One particularly memorable question came from a building supply company where male construction workers would sometimes enter the store without shirts, making female employees and others uncomfortable. I suggested some low-key strategies to encourage the men to dress more decently.

I’ve also had opportunities to answer journalists’ questions about moral issues in marketing, such as:

- Do Barbie dolls positively impact body image? The New York Times

- How can toys be more accessible? National Public Radio

- Is pay-day lending moral? U.S. News & World Report

- Should sports teams have people as mascots? WTOP Radio, Washington, DC

- Are fantasy sports ads promising unrealistic outcomes? The Boston Globe

And, in my own marketing work, I’ve sometimes encountered ethical questions, such as during a recent nonprofit board meeting. We were brainstorming attention-grabbing titles for an upcoming conference, when one member somewhat jokingly suggested including the F word. Fortunately, the idea didn’t gain traction, as others indirectly answered ‘No’ to the question, “Is it right to promote a conference with an expletive?”

These experiences, along with my research and writing, lead me to conclude that people are who we can depend on to ask important ethical questions, not AI.

So, if it’s up to us, not machines, to be the flag bearers of morality, what should we be wondering about AI ethics? Here are 12 important questions marketers should be asking:

1) Ownership: Are we properly compensating property owners?

Late last year, the New York Times filed a copyright infringement lawsuit against Microsoft and ChatGPT, alleging that the defendants’ large language models trained on NYT’s articles, constituting “unlawful copying and use.” Now eight more newspapers, including the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News, have done the same.

2) Attribution: Are we giving due credit to the creator?

In cases in which creators give permission for their work to be used for free, they still should be cited or otherwise acknowledged – something that AI is notorious for neglecting or even worse, fabricating.

3) Employment: What’s AI’s impact on people’s work?

In one survey, 37% of business leaders reported that AI replaced human workers in 2023. It’s not the responsibility of marketing or any other field to guarantee full employment; however, socially minded companies can look to retrain AI-impacted employees so they can use the technology to “amplify” their skills and increase their organizational utility.

4) Accuracy: Is the information we’re sharing correct?

Many of us have learned from experience that the answers AI gives are sometimes incorrect. However, seeing these outcomes as much more than an inconvenience, delegates to the World Economic Forum (WEF), held annually in Davos, Switzerland, recently declared that AI-driven misinformation represented “the world’s biggest short-term threat.”

5) Deception: Are we leading people to believe an untruth?

Inaccurate information can be unintentional. Other times, there’s a desire to deceive, which AI makes even easier to do. Deepfakes, like the one used recently to replicate Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi will become increasingly hard to detect unless marketers and others call for stricter standards.

6) Transparency: Are we informing people when we’re using AI?

There are times, again, when AI use can be very helpful. However, in those instances, those using AI should clearly communicate its role. Google sees the value in such identification as it will now require users in its Merchant Center to indicate if images were generated by AI.

7) Privacy: Are we protecting people’s personal information?

I recently asked ChatGPT if it could find a conversation I had previously with the bot. It replied, “I don’t have the ability to recall or retain past conversations with users due to privacy and security policies.” That response was reassuring; yet, many of us likely agree that “Since this technology is still so new, we don’t know what happens to the data that is being fed into the chat.” Is there really such a thing as a private conversation with AI?

8) Bias: Are we promoting bias, e.g., racial, gender, search?

For several years, there’s been concern that AI-driven facial recognition fails to give fair treatment to people with dark skin. Women also are sometimes targets of AI bias such as when searches for topics like puberty and menopause overwhelming return negative images of women.

9) Relationships: Are we encouraging AI as a relationship substitute?

Businesses like dating apps, social media, and even restaurants can assist people in filling needs for love and belonging. However, certain AI applications aim to replace humans in relationships entirely. After talking with a 24-year-old single man who spends $10,000/month on AI girlfriends, one tech executive believes the virtual-significant-other industry will soon birth a $1 billion company.

10) Skills: How will AI impact creativity and critical thinking?

The title of a recent Wall Street Journal article read, “Business Schools Are Going All In on AI.” It’s important that future business leaders understand and learn to use the new technology, but there also naturally should be some concern, e.g., When it’s so easy to ask Lavender to draft an email, will already diminishing writing skills continue to decline? Or, with the availability of Midjourney to easily produce attractive images, will skills in photography and graphic design suffer?

11) Stewardship: Are we using resources efficiently?

Some say AI’s biggest threat is not immediate but an evolving one related to energy consumption. Rene Haas, CEO of Arm Holdings, a British semiconductor and software design company, warns that within seven years, AI data centers could require as much as 25% of all available power, overwhelming power grids.

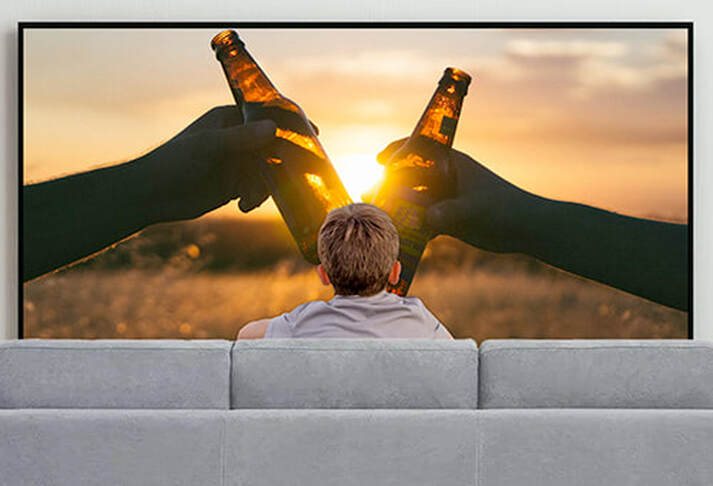

12) Indecency: Are we promoting crudeness, vulgarity, or obscenity?

For many people, AI’s impact on standards for decency may be the least of concerns; however, it also may be the moral issue that needs the most human input. An AI engineer at Microsoft intervened recently by writing a letter to the Federal Trade Commission expressing his concerns about Copilot’s unseemly image generation. As a result, the company now blocks certain terms that produced violent, sexual images.

Microsoft’s efforts to uphold decency remind me of something my father would do for our family’s promotional products company forty or fifty years ago. Long before the Internet, let alone AI, most major calendar manufacturers included a few wall calendars in their lines that objectified women by showing them wearing little or nothing, strewn across the hoods of cars or in other dehumanizing poses.

So, each year when the calendar catalogs arrived, before giving them to the salespeople, my dad would cut-to-size large decal pieces and paste them over every page of the soft porn pictures. Some customers paging through the catalogs and seeing the pasted-over pages would ask, “What’s under this?” to which my dad would answer, “That’s something we’re not going to sell.”

Long before the customers had asked their question, my father had asked his own question, “Is it right to sell calendars that oversexualize and objectify women?” and answered it “No.” Hopefully, fifty years from now, regardless the role of AI, there will still be people thoughtful and concerned enough to ask ethical questions.

To hold ourselves and AI morally accountable, we don’t need to have all the answers. We do, though, need to be thoughtful and courageous enough to ask the right questions, including, the most basic one “Is this something we should be doing?” Asking questions is key to Mindful Marketing.

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed