author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

The inquiry wasn’t entirely unexpected. We discuss ethical issues often in my classes, and sometimes students ask my opinion about questionable strategies they’ve seen in the news or that they imagine companies might use. However, this question wasn’t hypothetical.

Grant (not his real name) had been working for several months as an intern with a company that sold the products of various manufacturers in a particular business-to-business industry. He provided the firm different forms of marketing support, including help with social media.

Now the company wanted to share in social media specific consumer questions and its responses, which would highlight as solutions specific manufactures’ products, but there was one problem: The company had no actual consumer questions along the lines of what it wanted, so some in the firm decided it would be easiest to create not just the questions but also imaginary consumers to ask them.

Grant didn’t wonder whether what his company was considering was unethical; he knew it was wrong. It probably helped him, however, to hear me validate his concern. His question to me was more about what he might do or say.

As we talked about the issue, one of the first things that came to my mind was Sports Illustrated’s recent moral lapse. The iconic magazine about all things athletic ran afoul of public opinion on a viral scale when it apparently used artificial intelligence to write articles that it attributed to human beings.

First off, the articles appeared fake; for instance, one suggested that volleyball can be hard to play without a ball. Second, the authors seemed contrived. One writer, Drew Ortiz, had no publishing history or social media presence, all while a website that sells AI-generated headshots was offering for sale the same suspicious-looking profile picture that Sports Illustrated used for him on its site.

Unfortunately, Sports Illustrated isn’t the only organization faking it. A recent Wall Street Journal article revealed that phony product reviews, especially on Amazon, are more rampant than most of us ever would imagine.

Grant understood and rejected such deception. He could tell his coworkers that it's unethical to deceive and that creating fake customers would represent that very infraction. However, his colleagues might not be receptive to such a blunt rebuke and indictment of their character, particularly not from an intern.

So, I suggested that he mention the Sports Illustrated example and delicately suggest that things could turn out badly for their own company if they followed a similar tack and their strategy were exposed.

I felt for Grant in this predicament, but I also was very glad that he not only recognized there was an ethical issue, he was conflicted enough by it that he wanted to talk about it. For me those two things represented a moral victory.

Having worked in business for about a decade and having taught ethics in higher education for a couple more, my strong sense is that many moral issues in business are either not recognized, or they’re rationalized away, or they’re simply ignored. Grant cleared each of those moral hurdles. He then went a step further by talking with me.

Why don’t more marketers and others do what Grant did? That’s a difficult question to answer short of some formal research. Maybe I’ll conduct such a study sometime, but in the meantime, I asked Grant to reflect on his decision process and actions, which he graciously did.

I first asked Grant how he came to see the tactic as a potential ethical issue. He responded:

“In the project proposal my manager asked me to make fake client profiles on our website and have them send messages to our Product Advisor Channel. We would then take each fake question and make an Instagram style reel answering it. These Q&A reels would be used to promote partnered manufacturers and create a new style of content for our media channels.”

“I questioned the ethics of this project because we would be claiming to have organic questions coming from clients, and our company would be giving advice and solving problems when the questions weren’t being asked by actual clients. In my mind this comes across as lying to our customers to get engagement, benefit our company, and our manufacture partners.”

However, Grant also showed discernment in recognizing the multifaceted nature of the issue:

“I also saw how doing this could benefit clients. If we were posing questions that were legitimate and providing truthful answers, I can see how it would benefit the community. There could be advice given by our professionals that could help clients, even if it was from an account that we claimed to be organic, when in actuality they were our own.”

Many ethical issues involve legitimate competing considerations, which is one of the things that makes them so challenging. If they were easy, we wouldn’t have dilemmas.

Second, I asked Grant why he decided to mention his moral concern to me. He replied:

“The reason I mentioned it to you was because I know that you are passionate about going about marketing the right way. More and more I feel like the lines between legal and ethical are being blurred. We see a lot of marketers that are not concerned with the ethics of their marketing or in some cases don’t even realize that they are being unethical in their practices. I know that you have experience in marketing and because of this I sought out your advice.”

I was glad that Grant thought of me as someone who cared about ethics and could act as a helpful sounding board. I’ve often benefited by having people in my life to turn to for opinions and advice. I was happy to offer the same to him.

Reflecting on this experience with Grant has made me think of factors that should influence a person’s ethical decision making. There are surely more, but Grant’s actions in this instance have led me to identify three very important considerations:

1. Recognition: Conventional wisdom has long held that the first step in overcoming a problem is to admit having one. Similarly, good managers know it’s ineffective to discuss strategies before identifying the underlying challenges. Moral decision-making should follow the same approach.

It’s likely that many people wouldn't bat an eye if they received the same request that Grant got from his boss. The directive didn’t set well with Grant, probably because of his upbringing and deep-rooted beliefs and perhaps also because of the priority marketing ethics have received during his college education.

2. Regard: Just because someone recognizes an issue doesn’t necessarily mean they think it’s a meaningful one. Some needs are naturally more important than others, which is why discernment is critical and with it genuine concern.

Occasionally, an unrepentant offender will say, “I knew it was wrong, but I did it anyway.” Even very smart people are capable of abhorrent things if they don’t care. Thankfully, Grant cared.

3. Recommendations: No one has all the answers. Instead of relying just on our own ideas and instincts to guide our actions, our outcomes will usually improve when we ask others for their input.

In deciding moral issues, it’s especially helpful to gain the advice of someone objective who doesn’t have a direct interest in the outcome but who also has insight into the type of issue at hand. Grant happened to ask me, but the most important thing is that he sought a second opinion from someone who could offer an unbiased and informed one.

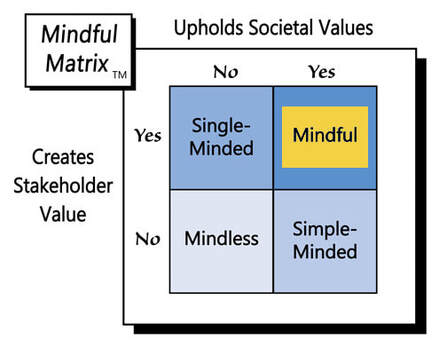

Whether Grant decides to refuse his boss’s request or honor it, perhaps with some caveats, his recognition of the problem, genuine regard for the outcome, and request for another’s recommendation place his moral decision-making ahead of that of most others. Grant’s actions also suggest that even before graduating college, he’s a practitioner of “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed