High school, college, and professional sports are peppered with teams named after people groups. In 2014, USA Today reported that of the 10 most popular high school mascot names, three had human connections: Vikings (#4), Warriors (#9), and Knights (#10). People names are also prevalent in Division I collegiate athletics, e.g., Knights and Spartans. Then there are professional sports franchises like the Dallas Cowboys, Milwaukee Brewers, and Cleveland Cavaliers.

In fact, nearly a third of teams in the United States’ four major professional sports leagues use people as mascots (39/123 = 31.7%). Here’s the breakdown by league:

- Major League Baseball (MLB): 13/30= 43.3%

- National Football League (NFL): 13/32= 40.6%

- National Hockey League (NHL): 9/31= 29%

- National Basketball Association (NBA): 4/30= 13.3%

To argue to change a team name that serves as a racial slur is pretty straightforward, but what about the dozens or hundreds of other anthropological nicknames? Is society failing to see now a practice that in years to come will be deemed abhorrent?

Apparently, few people objected in 1933 when George Preston Marshall changed the name of the then-Boston-based football franchise from Braves to the current one. Likewise, few appeared to challenge the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s decision in 1967 that gave the name legal protection.

In 1972, a variety of Native American organizations asked team president Edward Bennet Williams for a name change, but their plea evidently gained little public support and ultimately failed to alter his attitude.

The point is this: Just as the majority of the population was apathetic about the need for the Washington football team name change for most of its history, people might look back 20 years from now and wonder, “How could individuals in 2020 have been so ignorant to have people as mascots for sports teams?”

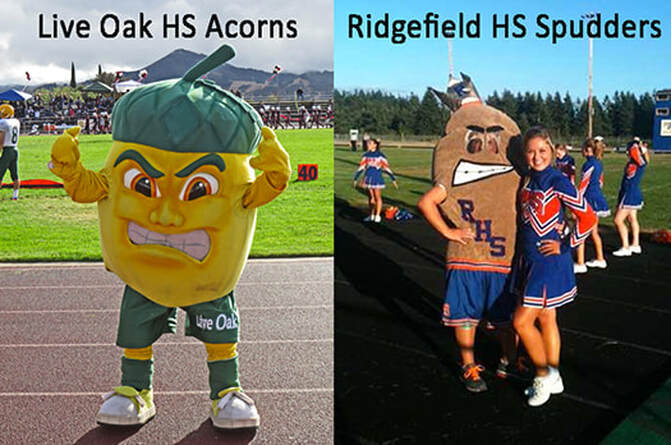

Now, however, many see being chosen as a team mascot as a sign of respect. After all, sports are about competing and winning. So, teams tend to pick mascots that are known for strength, speed, or ferocity or that possess some other desirable qualities that might reflect positively onto the franchise. Although sports teams called Acorns and Spudders actually exist, they are the exceptions. Instead, most team names are chosen because they suggest power and inspire confidence, like Wildcats and Warriors.

At first glance, Merriam-Webster’s definition of mascot reinforces the notion that being chosen as one is a positive thing: A mascot is “a person, animal, or object adopted by a group as a symbolic figure especially to bring them good luck.” How many people, however, want to be someone else’s good luck charm? Most people probably want to be the one enjoying success, not the token symbol responsible for helping someone else win.

A mascot, therefore, is a kind of ‘second class citizen,’ more of a possession or pet than a person. Of course, many mascots are actual animals, kept in cages or put on leashes and paraded in front of fans on gameday. Although mascots are typically chosen for their prowess, it's strength subdued in service to another.

At this point, some of you may be understandably thinking, “Relax! They’re just mascots. Sports are supposed to be fun!” I get that. I’ve appreciated mascots for many years and still do.

When I was much younger, I played for Danville, PA’s high school basketball team, whose mascot name still is the “Ironmen” (granted, not very gender friendly); the town was a key player in America’s 19th century iron industry. I’m also a long-time fan of the NFL’s Pittsburgh Steelers. Honestly, I never thought much about implications of these mascots being people . . . until now.

Would an iron mill or steel mill worker mind that their occupation was selected for mascot status? I'm speculating, but my guess is they wouldn’t; in fact, they might even feel honored. Their reputations as occupations that require unique physical and mental toughness probably makes their selection seem complimentary.

These two examples, however, help identify a potentially important distinction: Not all human mascots involve occupations, which people self-select. Some mascots are based on demographics like race and ethnicity (e.g. Cleveland Indians), over which people have no say.

That lack of choice is compounded by the issue of stereotypes. Any human mascot suggests a certain image for all those belonging to the demographic. For instance, the name Braves implies that all Native Americans are courageous and strong.

But, what could be bad about being perceived as strong and courageous? Aren’t they attributes that anyone would want? Perhaps they are, but the reality is, not everyone has them to the same extent. For Native Americans, that 'positive stereotype' might negatively impact them in at least two ways.

First, the Braves mascot stereotype might make those who weren’t born with as much natural strength or courage feel inadequate, like they’re not living up to an important social standard. Second, a seemingly positive stereotype still pigeonholes people, or presents an unnecessarily narrow or inaccurate view of their abilities.

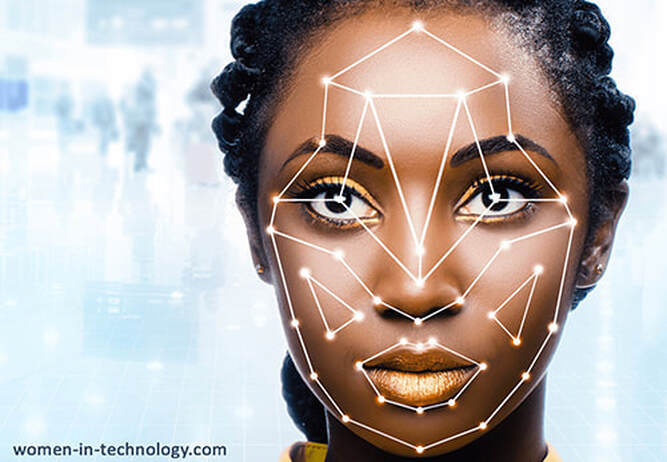

For example, I’ve been around sports enough to know that African American men are often stereotyped as great athletes. At first blush, that stereotype may seem positive, but if you’re an African American man, you may not appreciate people assuming that you played and/or excelled in sports, especially if you never did. You also wouldn’t like it if people discounted your intellect, as they sometimes do for athletes, inaccurately assuming that a strong body means a weak mind.

There really is no such thing as a positive stereotype. Unfortunately, mascots perpetuate stereotypes, which may not be an issue for animals or inanimate things but can be problematic for people if the mascot is tied to a demographic like race or ethnicity that individuals do not choose.

In more recent years, it seems that sports leagues have become more ‘enlightened,’ as it’s rare for expansion teams to be given human names. For instance, since 1976, six new teams have entered the NFL, but only one was given a people name—the Houston Texans, which is not directly tied to race or ethnicity.

The Washington Post reports that the Cleveland Indians are now considering a name change. It may not be long before other teams named Indians, Braves, Chiefs, etc. do the same. Projecting further into the future, it’s conceivable that some of sports’ most storied franchises, e.g. Celtics, Fighting Irish, will do the same.

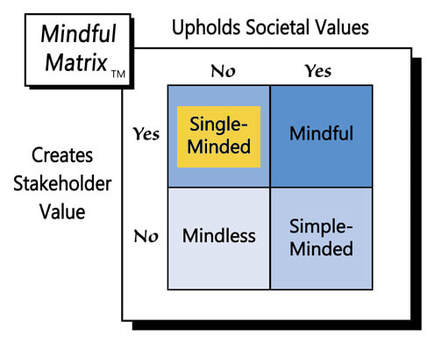

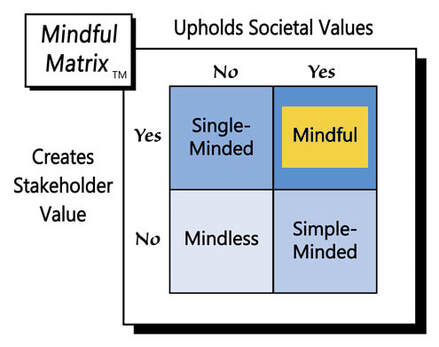

Mascots related to occupations, which people choose, can likely stay. However, team names based on race or ethnicity should be retired because of the narrow and unfair stereotypes they project. Years from now, if not sooner, people will see such team names and call them “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed