In an age of artificial intelligence and deepfakes, it’s not surprising that some brands are promoting themselves using people who aren’t people. Enter “virtual influencers”—digitally-developed endorsers who plug products not because they like the brand and want the money but because they were programmed to promote.

Perhaps the best known virtual spokesperson is someone/thing named Miquela Sousa, or Lil Miquela. From the splattering of freckles across her youthful face to her complaints of cold temperatures outside, Miquela looks and acts like a real person; however, she’s actually an avatar, the creation of Brud, “a mysterious L.A.-based start-up of ‘engineers, storytellers, and dreamers’ who claim to specialize in artificial intelligence and robotics.”

The company crafted Miquela’s persona to be that of a “19-year-old Brazilian-American model, musical artist, and influencer” who appears to hang out in hip New York and Los Angeles locales, with real-life celebrities. The avatar’s carefully curated personal brand has made her alluring to millions of real-life fans, including more than 43,000 subscribers on YouTube and over 1.6 million followers on Instagram.

That large of a following also makes Miquela highly marketable, which, after all, is her reason for existence. Although, a computer generated influencer (CGI) can’t really use brands, she showcases ones such as Coach, Balenciaga, Ouai, and Proenza Schouler. The promotional potential of Miquela and her fellow avatars (e.g., Blawko) certainly is real, as further evidenced by Brud recently raising $6 million in venture capital and Time placing Miquela among its “25 Most Influential People on the Internet” along with the likes of Kayne West and Kylie Jenner.

But, potentially big fan-bases are not the only attractive attributes of virtual influencers compared to real ones. Digital beings don’t need to be paid. Contrast those zeros to the seven-year $75 million sneaker endorsement deal basketball phenom Zion Williamson just signed with Nike.

Virtual influencers also can be precisely controlled to do and say exactly what advertisers desire, ‘on- and off-camera.’ Contrast that certainty with the risk inherent with real human endorsers, such as Tiger Woods, whose 2009 sex scandal caused two of his biggest sponsors, Gatorade and AT&T, to bail.

There seems to be real value in using unreal influencers, but as this blog always suggests, just because marketers can, doesn’t necessarily mean that they should. So, the question: Is it ethical for organizations to employ virtual influencers?

The thought of “employment” raises an immediate concern: Will digital endorsers put real ones out of work? It seems that some displacement is inevitable: If Miquela is promoting Coach, the brand probably doesn’t need as many flesh-and-blood models or actors.

On the other hand, there are also now new jobs. Someone needs to create and manage the digital personas. So, an argument about unemployment can be countered by the age-old logic that people always need to adapt their job skills in order to keep pace with new technology and not be displaced by it: To stay employed, people who dug holes with shovels needed to learn to drive backhoes and bulldozers.

For what it’s worth, my prediction is that virtual influencers will proliferate to a point of saturation, after which the pendulum will swing back in the opposite direction, at least somewhat, as consumers reaffirm their appreciation for real people’s authenticity, genuineness, and unmanipulated humanity.

For me, the biggest ethical concern surrounding virtual influencers is the potential for deception. As consumers, it’s critical that we recognize when someone is sharing an objective, unbiased recommendation versus one with some corporate connection. There’s not necessarily anything wrong with paid endorsement, but consumers need to know when they’re experiencing it so they can raise their perceptual defenses and properly interpret the message.

For example, as a college professor, I often speak with prospective students and their families about their college choice. They expect me to describe my school in a positive light and understand that I can’t be completely objective. However, if in some social setting I happened to have a conversation with a family, without revealing my association, they might gain an unreasonably favorable impression of my school because they didn’t know that the institution I described was my employer.

For virtual influencers, the potential for deception is different in one way but very similar in another. For instance, when Prada used Miquela to promote its 2018 collection, people probably recognized the ads as corporate messages, not an average consumer’s unbiased recommendation. However, to the extent that viewers didn’t realize Miquela was 100% digital, they may have been deceived.

The reason is that there’s a reasonable expectation that endorsers, whether paid or unpaid, either use the product they’re promoting or have some special knowledge about it that makes them reliable sources of information. For example, I earned my bachelor’s degree from Messiah College and have taught there for nearly 20 years, which should give me some credibility as an endorser. It’s impossible, however, for a virtual influencer to use or otherwise experience the brands they advocate because virtual influencers are not real.

When we see a human endorser in an ad, we assume they’re getting paid, which lessens their perceived objectivity. Still, even if they’re like Zion Williamson and receiving a boatload of money for their support, it’s reasonable to think that they wouldn’t risk their reputation with a brand in which they didn’t believe. People who can command significant sponsorship dollars usually have various endorsement options and can choose reputable ones.

Although Miquela can be pictured wearing or holding Prada products, she can never experience them because she isn’t human. But, if people believe she is real, they can incorrectly assume that her actual interaction with the brand allows her to make sound judgments about it. In short, consumers can be deceived.

Some may be thinking, “But, virtual endorsers really aren’t new, so hasn’t the potential for deception existed for decades?”

It’s true that companies have been using various types of animated endorsers for a long time, e.g., the Pillsbury Dough Boy, Tony the Tiger, the Energizer Bunny. In the 1950s, Pepsodent created Susy Q, an original cartoon character, to promote its toothpaste. More recently, some companies are offering to create unique animated spokespeople that even small businesses can afford.

The difference is the technology used to create Miquela and similar virtual influencers is much more sophisticated, making it increasingly difficult for consumers to distinguish who’s human and who’s not. Therein, again, lies the problem.

When we can tell that animated brand ambassadors aren’t real, we’re under no illusion that they use the products. However, when we believe a spokesperson is human, we assume that they use the product or have some special knowledge about it, which may give us unwarranted confidence in their recommendation.

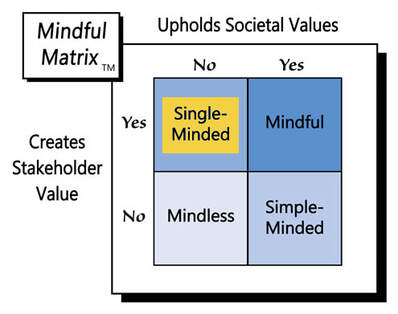

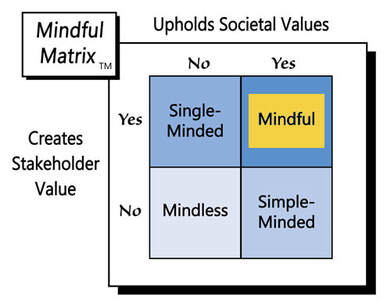

It’s fine for organizations to use animated beings to promote their products, but they should be careful not to mislead consumers by making the influencers so real that they seem human when they’re not. That kind of deception may sell products but it is really “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed