Why remember an accident more than two years past that took a single life, when 17 people riding a duck boat on Table Rock Lake near Branson, Missouri drowned just a week ago? The reason is personal: I knew Allison Warmuth.

Several years before, Allie had been a student in one of my marketing classes. I quickly learned that she was a bright and hard-working student, as well as a kind and compassionate person. She wore a warm smile and exuded charm that endeared her to others.

I was Allie’s teacher for only a few months, but the latest Duck Boat accident has evoked thoughts of her untimely passing, returning sadness to me and others who knew her. It’s hard to image the pain that those closest to such accident victims feel, having suddenly lost their brother or sister, husband or wife, daughter or son . . .

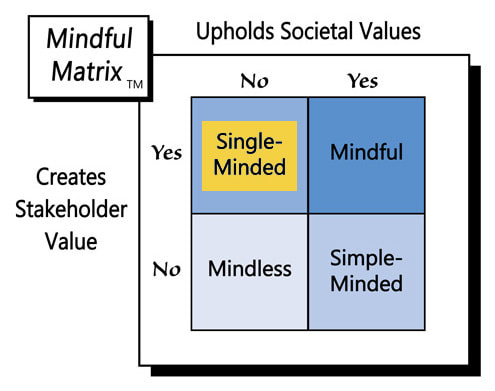

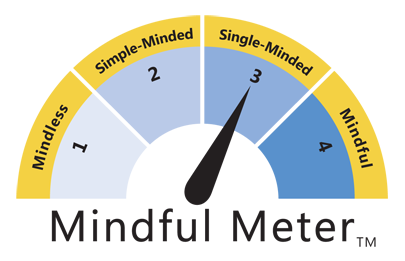

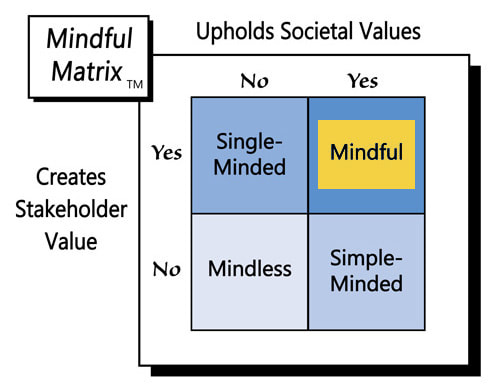

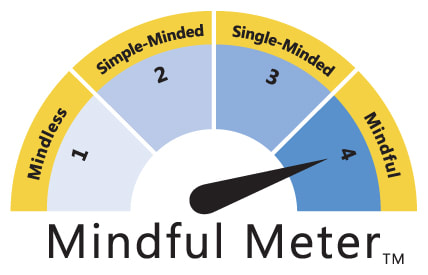

Mindful Marketing didn’t exist when Allie was a student. Today other marketing faculty and I use the Mindful Matrix with our classes to assess the marketing actions of organizations like Ride the Ducks. I wonder what a sharp student like Allie would have said about duck boats, not knowing that one would one day take her life, or that similar vessels would be responsible for the deaths of dozens of others.

Over the past 19 years, 43 people have died in duck boat-related accidents. Foreshadowing the Branson tragedy, thirteen people passed away in 1999 when a duck boat sank on a lake near Hot Springs, Arkansas. In 2010 in Philadelphia, two tourists died when a tugboat pushed a barge into their stranded duck boat.

The amphibious vehicles also have been responsible for several fatalities on land. In addition to Allie’s death, a woman fell backward from a duck boat in a parking lot in Boston in 2003, while taking a picture. Also, in 2015, “five college students were killed and more than 70 people injured when a duck boat veered into a charter bus on a bridge above Seattle's Lake Union.”

It’s important to realize that one company does not own and operate all of the nation’s duck boats; rather, several different firms run tours in select cities around the country. For instance, Original Wisconsin Ducks®, located in Wisconsin Dells, WI, bills itself as “the ONLY duck tour in the world in continuous operation since 1946.” Meanwhile, “Ride the Ducks” offers duck boat tours in Branson, MO; Seattle, WA; Stone Mountain Park, GA, and Guam. “Boston Duck Tours” is yet another private company, providing tours just in its namesake city and claiming to be “Boston’s most popular tour.”

Our course, what all of these companies have in common is their use of the distinctive duck boat, a World War II-era vehicle used to transport troops and supplies from ship to shoreline during beach invasions. Duck boats reportedly were responsible for delivering over 40% of over-beach supplies during the first four months of the invasion of Normandy.

During combat, a complex system of switches and levers kept the boats afloat by cranking the propellers, managing tire inflation, and pumping water out of the hulls. Some of the duck boats used today, including the one that sank in Missouri, date back to WW II. Most of those boats have been retrofitted in certain ways, including cabin extensions to accommodate more passengers.

The obvious benefit of a duck boat is that it can operate both on land and in water. Like a printer that also makes copies, dual-purpose can be a plus. The problem with some multi-functional devices, however, is that they do neither of their main tasks especially well, i.e., they’re ‘jacks of all trades, masters of none.’

Attorney Andrew Duffy, who has handled cases involving duck boat fatalities in Philadelphia, supports that description and then some. He calls the vehicles “death traps” that are “not fit for water or land because they are half car and half boat.”

On land, the main issue is visibility. Duck boats were designed to travel up empty beaches, not to navigate crowded city streets, which pose challenges for their considerable length and girth. More importantly, the vessels’ high elevation and long bows create a wide, five-foot-high blind-spot that makes it easy for operators to overlook smaller vehicles and pedestrians. Such design contributed to Allie’s death on that fateful day in April.

In water, duck boats’ relative lack of buoyancy causes them to sit lower in the water than many other boats, which becomes an even greater issue in bad weather like that on the day of the Branson disaster. Perhaps the biggest dangers, though, are the fixed canopies and roll-down window covers. Duffy explains: “When you are cruising along in a normal boat, if it capsizes you go [out of the boat and] into the water. With duck boats, you have the opposite effect. The canopy literally acts to drag you down with it.”

Duffy adds that the “heavy cellophane” many duck boat companies use for windows makes escape from a sinking craft even more difficult. Furthermore, passengers who don life jackets are at greater risk of being trapped underwater, as the vests push them upward and into the submerged canopy.

But, 43 deaths in about 20 years is miniscule compared to 40,100 U.S. motor vehicle fatalities in 2017. So, should we really be concerned about duck boats?

One thing to consider is that the total number of motor vehicle excursions in the U.S. in a year is undoubtedly many times the number of duck boat tours over the past two decades, so it should be expected that there will be many more ‘non-amphibious’ motor vehicle accidents than amphibious ones. Furthermore, when we climb into cars and onto buses, we assume the risks because we usually don’t have other options: We need to get to work or school, and motor vehicle transportation is the only reasonable way to do so.

On the other hand, no one needs to take a duck boat tour. It’s a low-intensity leisure activity that’s easy to substitute, so the risk to those on or near the vehicles should be virtually zero. Yes, some recreational pursuits like bull riding and mountain climbing place people at considerable risk of death or injury, but well-trained and adventurous adults knowingly accept those risks. Families with young children, senior citizens, and others simply looking to see the sights of a city shouldn’t have to worry about dying on a tour.

However, some duck boat companies, like Original Wisconsin Ducks, which operates the nation’s largest fleet of ducks (92), claim to have never had an accident. Should they be allowed to operate as-is?

That’s a decision that objective experts need to make; however, it’s worth noting that Ride the Ducks in Branson also apparently never had an accident before 17 people died, even though company spokesperson Suzanne Smagala-Potts has said that “The safety of our guests and employees is our number one priority” and despite a private safety inspector having warned the firm about life-threatening design flaws in its vessels less than a year before the fatal accident.

It’s also worth noting that James Hall, former chair of the National Transportation Safety Board, has suggested that duck boats are inherently dangerous and should be banned from commercial recreational use. Hall doesn’t believe there’s a way to make the vehicles safe, especially during bad weather.

What would Allie Warmuth say about duck boats? As a sharp businessperson, she would likely appreciate the tours’ strong consumer demand. However, as a rational and caring human being, she also would recognize that revenue potential doesn’t outweigh the risk to life. As a result, duck boat tours should be considered “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Note: Allie’s family has created a Facebook page to help prevent similar accidents and to ensure the safety of others. Please consider visiting and liking Street Safety for Allie.

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed