Given that each day over 93 million people play Candy Crush Saga, the widely popular mobile game for iPhone and Android, Claire’s dilemma likely duplicates itself thousands of times a day. Of course, King Ltd., the maker or Candy Crush, wants many more of those millions of people to plunk down cash to play, but should people feel compelled?

In 2015, mobile is expected to become gaming’s biggest market, worth an estimated total value of more than $25 billion a year. By 2017 that global revenue will likely be $60 billion. With so much money being made, why should game makers need people to pay more? Aren’t they just being greedy?

True, those are significant sales, but it’s worth noting that they’re spread over a growing number of mobile game developers in an increasingly competitive industry. GameSalad, a company that develops the developers and claims more than 80 of the top 100 games in the U.S. App Store, reports that it has helped over 750,000 developers publish more than 65,000 games. At the same time, a relatively small number of mobile companies in the U.S. (247 to be exact) can claim revenues of more than $1 million. Meanwhile, “the 10 highest-grossing games rake in 43% of world-wide mobile-game revenue.”

So, what about Claire? There she is, engrossed in the game when her enjoyment is cut short. Is it right for mobile game companies to lure consumers with free play, then monetize their motivation to expand their experience.

The key to answering this question is to know whether any of the following are at play:

- Deception: Does the company mislead players in terms of what’s free and what’s not?

- Coercion: At a key moment, does the firm somehow force players to purchase extended playtime or other benefits?

- Manipulation: Has the company concocted an elaborate scheme that leads players unwittingly down a plan toward payment, which is virtually impossible to avoid?

If the answer to each of these questions is “No,” i.e., there is no deception, coercion, or manipulation, then it’s likely that the company’s approach is ethical. Furthermore, in such situations Claire and other game players have reaped benefits from their time of open access. Even if play doesn’t continue beyond that point, they still have had an inexpensive and enjoyable experience.

Players, therefore, are under no compulsion to continue playing at a cost. Yes, they may experience some disappointment if they quit, but they still are able to walk away without any really negative repercussions and without needing to forfeit the gratis gratification they’ve already received.

This ability to walk away satisfied seems validated by the stat that “less than 3% of all mobile-game players make any in-game purchases.” At the same time, those who do pay to play spend $5-$25 a month on average, and a very small number of heavy users (“whales”) spend $50-$100 a month.

Is it wrong for these players to pay to play? Not as long as they are doing so voluntarily with a realization of how much their spending, and with discretionary income that can support the habit. While $1,200 a year seems excessive to me for mobile gaming, there are people who spend ten times that amount annually on other forms of recreation.

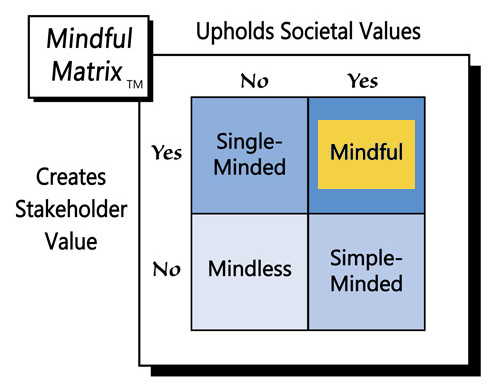

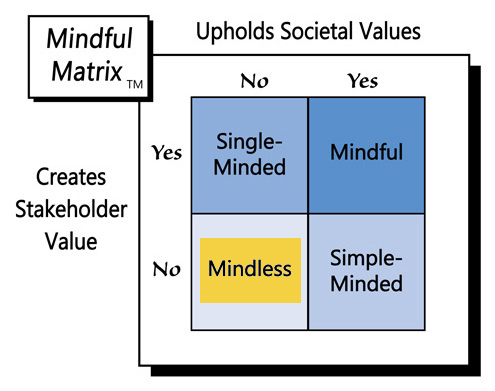

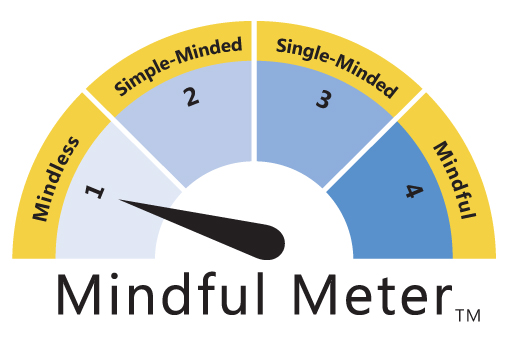

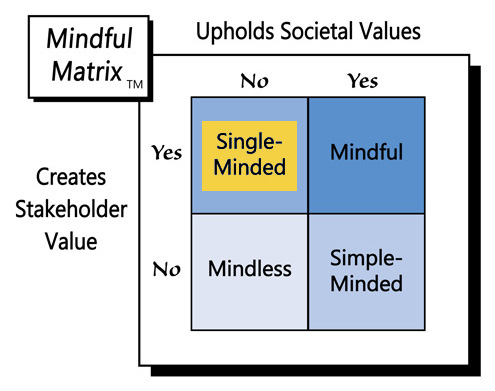

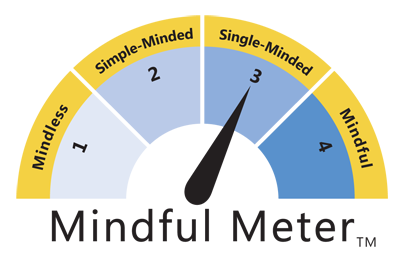

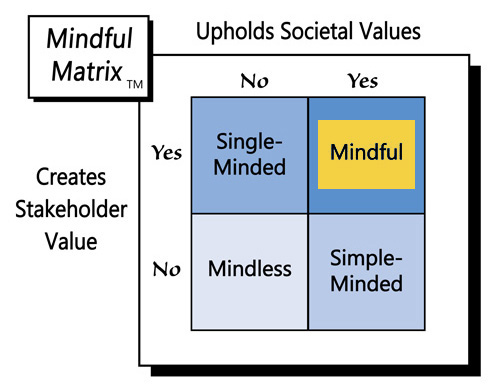

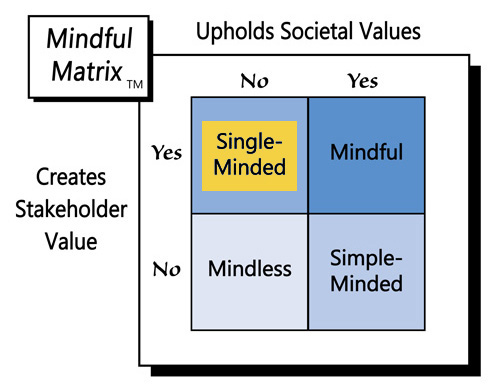

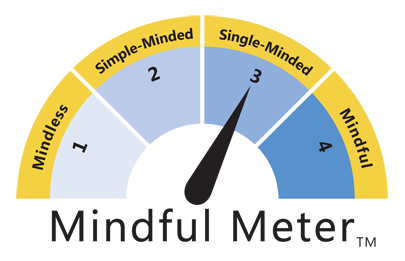

Given the tremendous growth of mobile gaming via the "freemium" model, it appears that the play-a-little-for-free approach creates stakeholder value. Likewise, there’s no inherent compromise of societal values, which makes giving Claire and others the option to pay to play “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed