The nation’s pizza deliver leader is very good at getting its products from its stores to our doors, but it seems less confident about our ability to do the same. For that reason, the company recently introduced “carryout insurance.”

Domino’s now promises: “If damage occurs to your carryout order after you leave the store, just bring it back and we’ll remake it for free.” The firm lists a few reasonable provisos: The order must be uneaten, with nothing missing, in its original packaging, and accompanied by a receipt. The firm also offers examples of accidents that qualify for a claim like slipping and falling, "my kid sat on it," and "a stranger sneezed on it." In other words, it seems like the company will cover just about any claim consumers make.

How much does the pizza insurance cost? According to Domino’s it’s “free for all customers.” Some may be thinking, “But, there are no free [pizza] lunches,”—customers must be paying for the insurance indirectly. That may be true; however, Domino’s doesn’t appear to have increased its prices. The company needs to be careful that the costs of its pies stay in-line with those of Papa John’s and Pizza Hut in the highly competitive pizza market.

It’s also likely that pizza insurance claims haven’t taken a significant bite out of the firm’s bottom-line, which raises a key question, “Do people really need pizza insurance?”

Let’s say that someone spends $30 on a pizza pickup order, then drops it while taking it out of their car. The accident may ruin their day, but it probably wouldn’t pose any significant financial hardship. People who can afford to spend $30 on takeout food generally can afford to lose $30 worth of takeout food.

Contrast that loss to a serious car accident, a home fire, or the death of a family’s primary breadwinner. Those events could prove financially devastating, if not insured.

Such scenarios remind me of advice my dad once gave me: Insure the big things that could break you; don’t bother to insure littler things like electronics and lawn mowers. Even though they may be somewhat costly to replace, it’s worth the risk because replacement wouldn’t be financial catastrophic. I also liked the line my Dad said to salespeople who tried to pressure him to insure small items: “All your talk of insurance is making me wonder about the quality of this product and whether I should be buying it.”

My father’s insurance advice is similar to that of Todd Erkis, a professor of finance and risk management at Saint Joseph’s University, who says that “Insurance is key to protecting yourself against financial ruin.” Consistent with that view, Erkis suggests that new college graduates should buy just four types of insurance in order to hedge against possible financial hardship: health, long-term disability, renter’s, and car insurance.

Writing for Mint Life, Nicholas Pell adds just two other types of insurance to buy: home owner’s, which is analogous to renter’s, and life insurance. New college graduates often don’t have dependents and, therefore, don’t really need life insurance, but those who do should use insurance to protect their survivors from poverty.

All this to say, people don’t need pizza insurance, even if it’s “free.” So, what is Domino’s doing? In the very crowded market for restaurant pizza, Domino’s is probably trying to gain a little bit of perceptual separation from its closest competitors. Papa John’s and Pizza Hut don’t offer carryout insurance, which makes Domino’s distinct.

However, while Domino’s may have created a difference, the insurance doesn't deliver any real competitive advantage. Again, people don’t need the insurance, so it probably won’t sway many purchase decisions. Furthermore, who ever thinks they might drop their pizzas? In sum, the insurance just doesn’t offer any measurable improvement to Domino ’s value proposition.

Still, Domino’s has savvy marketers. The company wouldn’t be so successful if it didn’t. The firm’s marketing team probably intends carryout insurance as more of a promotional strategy than a product enhancement. In other words, it doesn’t matter if the insurance causes people to buy more pizzas, as long as publicity and word-of-mouth about the unusual offering helps keep Domino’s top-of-mind. That added exposure, in turn, should lead to more pizza purchases.

But would the firm really go to such lengths just for promotion? It's done so before.

Prior to carryout insurance, the company’s “Paving for Pizza” campaign represented a similar strategy. Domino’s promised to patch potholes around the country so the road hazards wouldn’t wreck pizza deliveries. Of course, a company as far-flung as Domino’s could never repair enough roads to actually make a significant delivery difference in most of its locations. However, the notion of a pizza company patching roads was so novel it captured press attention, as well as created some community goodwill. In short, the program seemed to be a very effective, albeit unconventional, means of pizza promotion.

Will carryout insurance, work as well for Domino’s? I doubt it. Despite the fact that I’m writing about it now and you’re reading about it, I don’t believe the company’s newest ploy will capture the interest or hearts of people like the paving program did.

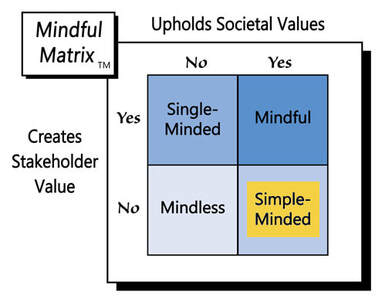

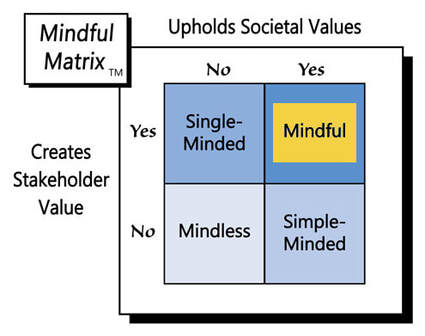

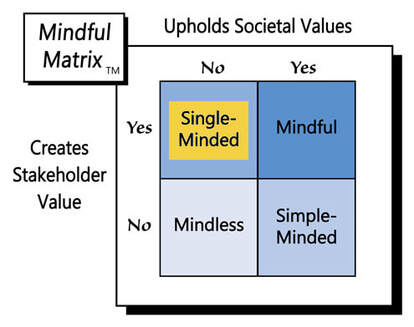

There’s nothing wrong with Domino’s promising extra protection for pizzas; in fact, it’s a nice extra benefit, if anyone ever needs it. However, that lack of real consumer value, teamed with minimal promotional impact, places carryout insurance in the box of “Simple-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed