author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

It was a Saturday evening when the emails hit my inbox within minutes of each other. They caught my attention because both were from furniture retailers that I never heard of before. Although I hadn’t been shopping for furniture, I knew my wife had been online helping our son find furnishings.

I asked her if she recognized the retailers. She said she had visited their websites earlier that day but hadn’t purchased anything or provided any contact information. Nonetheless, she also had started receiving emails from them.

Most of us have experienced the remarketing that happens when we search for a specific product online and soon after, ads for the same product start appearing on webpages we visit. However, that kind of digital targeting is typically confined to websites; it doesn’t lead to us receiving emails since we didn’t provide an email address.

While I was surprised that my wife had received emails from the two retailers, I was baffled by how I’d been added to their lists.

I understood that it’s easy for companies to access data linking our email addresses to our internet protocol (IP) address, “the unique identifying number assigned to every device connected to the Internet.” That connection is evident each time we complete an online form that asks for our email address, among other personal information.

Companies that don’t harvest that data themselves also can buy it from those who do. The market for data brokering is huge – now a $138.9 billion industry that’s expected to top $229 billion by 2025.

Big tech companies like Facebook and Google, as well as credit bureaus like Equifax and Experian, are among the biggest players in the data collection market. These organizations often say they don’t sell customer data; rather, they “share” it with their advertising partners. Of course, advertisers pay these big data collecting companies to run their ads, so selling vs. sharing seems like semantics.

Having exhausted the extent of my digital data-sharing knowledge, I turned to an expert. Dan Shaffer was once a BIS major and a student in my Marketing Principles class. He’s since risen to Director of Marketing Operations at WebFX one of the world’s leading digital marketing companies. I asked him how the two furniture retailers, who were completely unknown to me, could have gotten my email address.

Shaffer said that the companies were likely using https://retention.com/ to tie my IP back to my email addresses via brokered data – a process that started when at some point my email address and IP address were paired, probably from an online form I filled or an email newsletter to which I subscribed sometime ago.

Even though my wife and I use different devices to access the Internet, and each device has its own unique IPv6, the first 14 digits of that number are the same for every device in our household. So, a company with data from both my wife and from me could connect our datasets and target not just an individual shopper but as Shaffer described, our “household’s browsing history and interests.”

So, to summarize, the two unknown furniture retailers found me by using a very specialized analytics service (Retention.com) that: cross-referenced myriads of data it either harvested itself or purchased from others, found correlations among my wife’s and my separate online activities, and used those connections to paint a digital picture of our household.

That’s a simplified view of what happened and how. Given the moral focus of Mindful Marketing, the bigger question is, should it have happened? Was it right for the two furniture retailers and Retention.com to put my wife on their email list and target me?

It’s interesting that Retention.com dedicates an entire webpage to answering the question, How is Retention.com Legal? Who else does that? Does your employer take time to explain why it’s legal? An organization that does so naturally makes us ask: Should I be worried? Are there reasons why this business may not be legitimate?

Retention.com makes a case for the legitimacy of its practices with a variety of alleged facts including:

- According to the US CAN-SPAM Act of 2003 you do NOT need an opt-in to send email marketing in the USA. In Europe, you do; but in the US, you don’t.

- To be CAN-SPAM compliant, all you need is an opt-out link in the communication, and you need to make it clear that it’s an advertisement, along with a few other requirements (see below).

The webpage goes on to discuss that the conventional definition of SPAM is email that is both unsolicited and bulk. However, Retention.com argues against that definition because although it comes from Spamhaus, which is “an important, and influential organization in Email Marketing,” “Spamhaus is NOT the US government.”

At the same time, Retention.com also claims that it complies with Spamhaus’ definition because it provides “verifiable consent, ie, a third-party opt-in date and time, and the URL of our partner website that they opted in to.”

Furthermore, the site argues that the emails sent thanks to its services comply with the main requirements of the Federal Trade Commission’s CAN-SPAM act:

- No false or misleading header information

- No deceptive subject lines

- Identifying the message as an ad

- Telling recipients where the sender is located

- Telling recipients how to opt out of receiving future emails

- Honor opt-out request promptly

- Monitor what others are doing on your behalf

To Retention.com’s credit, I can confirm that the emails I received from the two furniture retailers complied with most of the seven stipulations above. However, one significant falsity appeared at the top of each email: “You’re receiving this email because you stopped by our site. Unsubscribe”

Before I received the first email from them, I didn’t even know these retailers existed; I certainly never visited their websites.

Given that my wife did browse the sites, perhaps the retailer and Retention.com could argue that “you” is plural, i.e., ‘you people,’ or ‘your household.’ Of course, even individuals in the same family or household often have very different personalities, preferences, and internet use patterns.

Why would a company want to risk annoying, alienating, or even offending potential customers, given the possibility that by targeting households one of the following could happen:

- Spoil a surprise – What if my wife was hoping to surprise me with some new piece of furniture? Well, she can’t now!

- Reveal sensitive information – Others don’t need to know that someone in their household is looking into treatment for a certain medical condition or for an attorney, a therapist, protection from domestic abuse, etc.

Besides being dishonest (“you stopped by our site”), it seems like Retention.com and these furniture retailers are taking a step backward in terms of best practices in marketing.

Ever since marketing began as a science in the mid-1900s, marketers have continually worked to refine their target markets, i.e., tailor them more and more to the needs of specific individuals vs. amorphous groups.

Now that digital media have enabled true one-to-one marketing and mass customization, why turn back the clock?

At the same time, I realize that Retention.com, like many digital marketers, is playing a numbers game. It doesn’t need to get my business for its clients. As long as its shotgun approach gets 15-20% of recipients to open the unsolicited emails and even smaller percentages to visit the retailers’ sites and make purchases, it’s probably providing ROI.

On its ‘right to exist’ page, Retention.com poses a rhetorical question that compares Spamhaus’ guidance to what’s legal:

Why abide by this definition, even though it’s considerably more restrictive than the law?

This question cuts to the heart of the difference between law and ethics and evokes a time-honored moral truism: Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.

First, there is at least one reason to believe that Retention.com’s practices do run afoul of the law, specifically concerning the Federal Trade Commission’s standard for truth in advertising, which mandates that “Under the law, claims in advertisements must be truthful, cannot be deceptive or unfair . . .” (1) Since I never visited the two furniture retailers’ sites, to say I did is blatantly untruthful.

Second, even if Retention.com is given a legal pass, it’s practices still raise moral questions, e.g., What really represents ‘opting in,’ and how might less-than-transparent and/or manipulative systems mislead or coerce consumers?

For instance, at some point months or years before, my wife and/or I may have clicked “yes” on terms-of-use agreements that in an array of opaque legalese said that certain companies could “share” our customer information.

Is there really informed consent when you have 1) practically no idea with whom your data will be shared and for what purposes and 2) you’ve been shopping online for a long time, the terms-of-use agreement is the last thing you need to check off before completing the purchase, and the agreement is 10 pages long, in 8-point type, single-spaced?

Just because a company like Retention.com can “legally” assimilate reams of data, find connections, and sell those association services to others, should it? Instances of deception and possible coercion suggest, “no.”

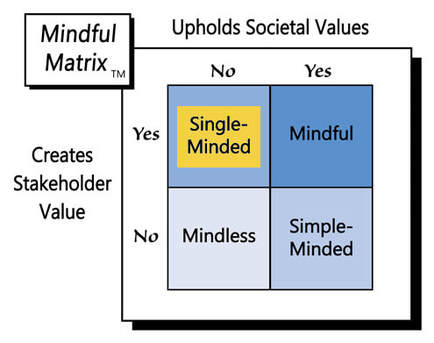

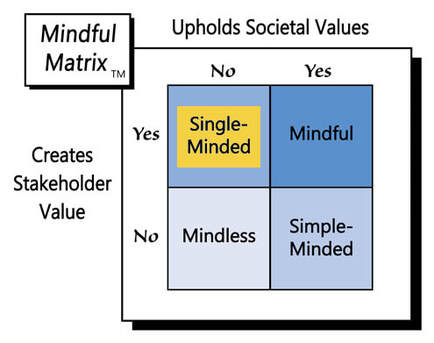

Despite my own unpleasant experience and critical analysis, Retention.com probably is helping to convert a small percentage of surprised email recipients to customers for its clients, making its data amalgamation and email inundation approach “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed