Besides these two teams’ woes, baseball has experienced struggles of its own. Some report declining TV viewership, due in large part to a decreasing interest in baseball among young people. Still, when it comes time for the World Series, engagement explodes, especially for diehard fans of franchises like the Cubs and Indians who have waited so long for success. Those teams and their surrogates, then, start to experience the opposite problem: how to satisfy fans’ overwhelming desire to partake in history.

That participation, of course, comes at a cost. Tickets for championship contests are always high, but those for this year’s Series are particularly pricey. At Chicago’s Wrigley field, “Face value for tickets ranges from $450 for infield club boxes to $175 for upper-deck seats.” Those list prices may seem expensive, but they’re nothing compared to what people are paying for tickets in the secondary market.

For this past Friday’s game at Wrigley, its first World Series game since 1945, the average resale price was $3,500. On the lower end of the scale, that mean includes standing room only and bleacher tickets averaging $2,167 and $2,969 each, respectively. On the upper end, field-level seats are commanding about $8,112 each. StubHub has even seen someone pay $23,402 each for two Game 7 seats located just above the Cubs dugout at Cleveland’s Progressive field.

Laws of supply and demand explain how sellers can command such extreme prices for seats to a three-and-a-half-hour baseball game and why buyers are willing to pay them. Wrigley Field’s capacity is just 41,688, and Progressive Field can handle even less, 35,225. The populations of Chicago and Cleveland, in comparison, are around 2.7 million and 390,000 respectively. Granted, not everyone in those cities wants to watch baseball, but many do, not to mention the tens of thousands of other fans who are willing to travel across the state and from around the country in order to see history being made.

Although the ‘how’ and ‘why’ of secondary market ticket sales are important, the question that really matters is a moral one: ‘Should individuals and organizations resell tickets to events like the World Series for prices far above their face value?' Or, in other words, is ticket scalping ethical?

First, it’s worth noting the legal standing of the practice. In the U.S., no federal law prohibits scalping, but “15 states ban the practice in some way, most labeling it as a misdemeanor with penalties including fines and/or up to a year in jail.” Among these states, there’s not a unified set of sanctions: While some states take a hard line, others states only prohibit the practice within 200 feet of the stadium entrance. These legal disparities are a good reminder that it’s problematic to base ethicality on legality.

Organizations should be able to resell products that they buy from others. That reselling is at the heart of every garage sale and grocery store. In both cases, as well as in thousands of similar ones, consumers benefit from the exchanges. In garage sales and other aftermarkets like eBay, people typically pay less for used items that still offer utility to the purchaser. Grocery stores, like most other retailers, sell new items (there’s not much demand for used food), at prices that are higher than what they paid for the products. So why aren’t these stores and every other retailer guilty of scalping?

The main difference is that these retailers provide value-added services that result in fair prices and convenience for consumers. Yes, I could go to Battle Creek, MI to buy my Kellogg’s breakfast cereal, but I’d rather drive a mile to my local grocery store where I can purchase the cereal and dozens of other products I need, at the same time. That great convenience far outweighs the higher price I might be paying.

In contrast, professional ticket scalpers, including online brokers, do the following, metaphorically: They beat me and other consumers to the grocery store and buy up its entire inventory of Kellogg's cereal, not because they want to eat it but because they know that we do. Then, when we arrive, they inform us that the store is all out of the cereal, but we can buy it from them at double or triple the price. Unlike grocery stores that charge very little for considerable value added, scalpers extract inordinately high premiums for doing something that we could easily have done ourselves—buy the tickets directly from the source, either online or at the stadium.

Another factor adding to the unseemliness of ticket scalping is that sporting events, concerts, etc. are highly unique, intangible products, not physical goods. If on a given day a store runs out of cereal, smartphones, or cars, consumers normally can do one of the following: buy a close substitute, drive to another store, or wait for the inventory to be replenished. Those options aren’t available for people wanting to experience special events, particularly not ones like a World Series game between two teams that together have been waiting 176 years for a championship.

Some may also wonder what the difference is between purchasing popular event tickets and buying corporate stocks. Besides the fact that stocks represent ownership in a company, both are intangible products, bought with the belief that their prices will rise, resulting in a return for the reseller. The main differences are the ones just described above. Unlike an event, a stock is not tied to a specific time and place, such that if you don’t buy and experience it today, the opportunity is gone forever. Likewise, for most people, stocks are more readily substitutable; that is, it’s relatively easy to find a similar investment. It’s impossible, however, to find another 2016 World Series Game 5, between the Cubs and Indians.

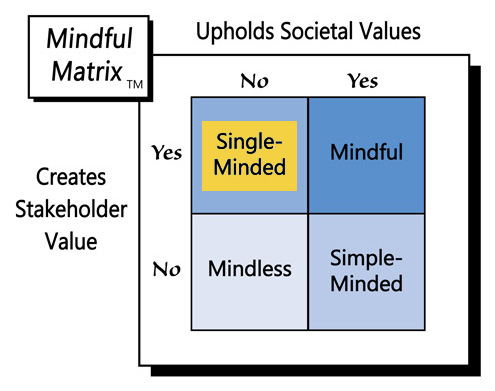

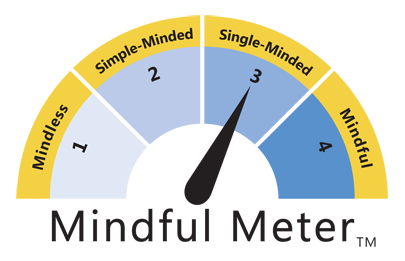

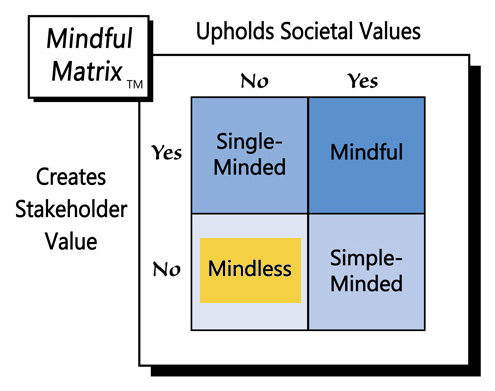

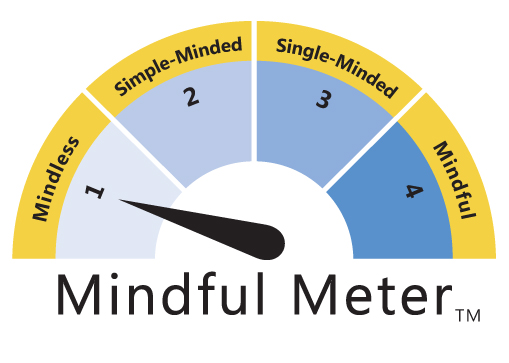

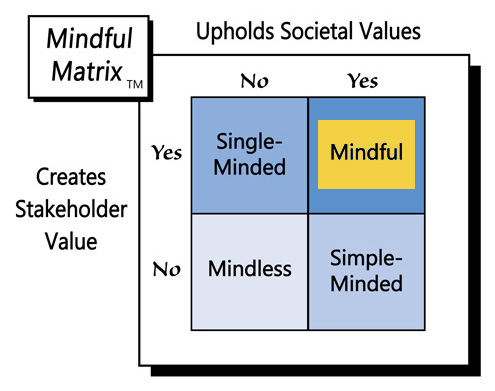

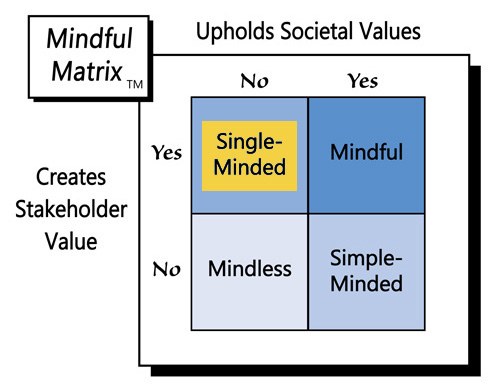

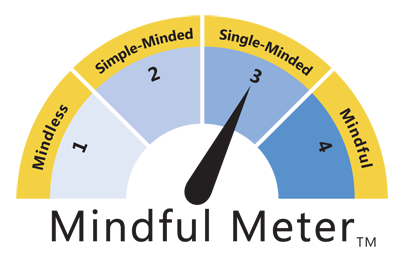

Given that people continue to pay the high prices that professional scalping produces, it appears that the practice creates stakeholder value: The scalpers are making out well and some consumers are getting what they want, albeit at a ridiculous cost. The grey market for tickets, however, fails to uphold societal values like fairness and respect. For these reasons, ticket scalping is an experience in “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed