author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Native advertising is the term used to describe “paid advertising where the ad matches the form, feel and function of the content of the media on which it appears.” Think of the approach as camouflage for commercials. Just as hunters wear green and brown to blend into a forest, native ads mimic the look and feel of their media surroundings so people don’t perceive that they’re promotion.

Native advertising has likely existed for more than a century, one of the earliest examples being John Deere’s agricultural magazine The Furrow, which contained “articles on agriculture and farming tips” alongside ads for the firm’s agricultural products. The entire magazine was, in essence, subtle promotion for John Deere; still, readers could probably easily distinguish the publication’s articles from its advertisements.

Today's native advertising is much more stealthy.

Scrolling through a Yahoo.com news feed recently, I saw sandwiched between a Telegraph article about Prince Harry and a MarketWatch piece on COVID-19, an interesting black and white photo of a woman playing pool along with the intriguing caption, “Pics Show A Gross Past To How We Used To Live.” I barely noticed in small type “Ad Autooverload” before hitting the hyperlink.

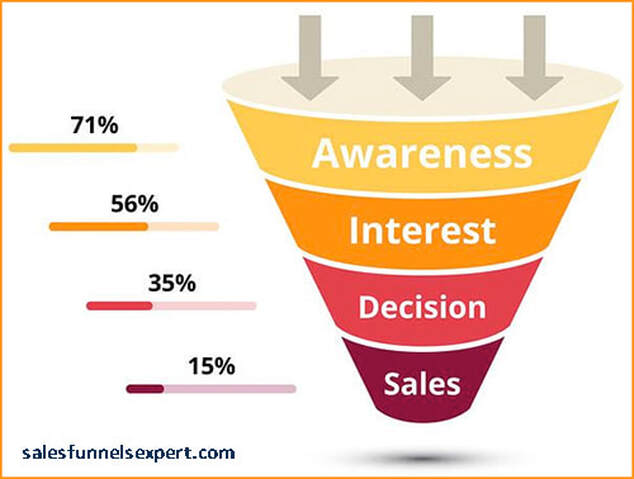

The link opened a new browser tab for autooverlaod.com with header menu items that included “Racing” and “Supercars.” The page also featured the start of a slideshow titled “Amazing Wild West Photos.” What Lamborghini’s have to do with Wyatt Earp wasn’t clear, but one could imagine that the prolonged progression of “wild west” photos enhances Auto Overload’s web metrics (e.g., time spent on the site, page views) for purpose of appeal to advertisers.

The use of such native ads has been increasing steadily with no signs of stopping. Media from BuzzFeed to The New York Times have incorporated the promotional approach, with some suggesting that native advertising “will soon become as mainstream as the TV ad.”

BigCommerce reports that in the U.S. in 2020, over $47 billion was spent on native advertising and that 62% of all digital advertising, or “six out of every 10 digital ads were native ads.” Furthermore, native ad spending is forecast to increase by 21% in 2021 to a staggering $57.27 billion.

Of course, an increase in native advertising is not a problem unless native advertising is a problem. So, why are 51% of consumers who know what native advertising is skeptical about native advertising?

The example above from AutoOverload serves as a good case for analysis. People are rightly wary of the ethics of native ads like this one because they have a propensity to deceive in two closely-related ways, which also violate Federal Trade Commission (FTC) guidelines.

1) Clickbait photo and caption: A sultry photo alongside the enticing text “gross past,” “wild west,” and “rarely seen,” represent a hard reach to reel people into something that’s likely different than what they expect, in more ways than one.

The use of these visual and verbal elements fits the FTC’s description of bait advertising: “an insincere offer to sell a product or service the advertiser does not want to sell, in order to sell something else . . . .” Again, there’s no reasonable connection between old west photos and automobiles. AutoOverload seems to be taking the somewhat deceptive approach just to increase its site traffic.

The approach can be called “somewhat” deceptive because, the website does deliver a series of old west photos; although, from what I saw, they don’t live up to the promise of “wild.” The greatest deception actually might be of AutoOverload’s advertisers. These sponsors, which include Volkswagen, probably believe they’re paying for pageviews from people interested in purchasing cars—a conclusion that likely is often not the case.

2) Subtle sponsorship: Most of us have regretfully clicked on a sponsored article or post thinking it was an objective news piece or something a private person shared. The frequency of this common experience is largely attributable to what native advertising so often tries to do: Make people believe what they see is not an ad.

One of the easiest ways to do so is to downplay the ad’s sponsorship. The AutoOverload ad sought such subtlety by using the shortest commercial identifier possible, “Ad,” instead of “Advertisement” or “Sponsored Post.” The ad’s commercial nature also might have been overlooked because “Ad” and “Autooverload” appeared in a smaller and lighter color font than that of the headline text.

Such understated endorsements may seem normal, but that’s likely because native advertising has made them so commonplace. This subtle sponsorship stands in stark contrast to most traditional ads on TV, radio, and billboards where sponsors want to be clearly identified.

Why don’t sponsors of native ads seek the same recognition? They do want to be known, but they first want to make sure that people click on their ads, which individuals often are not inclined to do if they know they’re ads. The following two quotes from LinkedIn’s B2B University expose the sneaky strategy:

- “Native ads mimic the look, feel, and function of a medium’s content, making it more likely that your audience will trust them.”

- “Native advertising is designed specifically not to look like an ad, making it harder to ignore. Instead, it’s designed to look like the rest of the content on the page. As a result, consumers interact with native ads 20-60% more than traditional banner ads.”

So, native ads pretend to be something they’re not in order to increase the probability that people will mistakenly choose them. In other words, the goal of most native advertising is to deceive.

The irony of native advertising’s casual acceptance of deception hit me squarely as I was scanning a daily newsletter from the American Marketing Association (AMA) and noticed the headline “Transparency Is the Clear Choice for Salespeople.” The article summarized the findings of a study published in the Journal of Marketing Research titled “Open Negotiation: The Back-End Benefits of Salespeople’s Transparency in the Front End.”

Contrary to conventional wisdom, the researchers found that “customers to whom the salesperson revealed the cost of a car at the beginning of the negotiation spent significantly more in the back end than others.” In other words truthfulness and transparency from the beginning of the buying process paid off not just morally but monetarily.

These results reminded me that the AMA has identified five core “Ethical Values,” which include honesty and transparency. More specifically, one of AMA’s three “Ethical Norms” explains the aim of fostering trust in the marketing system:

“This means striving for good faith and fair dealing so as to contribute toward the efficacy of the exchange process as well as avoiding deception in product design, pricing, communication, and delivery of distribution” [boldface added for emphasis].

Besides flying in the face the AMA’s clearly articulated professional standards, the deception-driven strategy of some native advertising also violates several specific FTC guidelines:

- “When the first contact between a seller and a buyer occurs through a deceptive practice, the law may be violated even if the consumer later finds out the truth.”

- “An ad is deceptive if it promotes the benefits and attributes of goods and services, but is not readily identifiable to consumers as an ad.”

- “Disclosure must be clear and prominent.”

- “Advertisers cannot use ‘deceptive door openers’ to induce consumers to view advertising content.”

- “Advertisers are responsible for ensuring that native ads are identifiable as advertising before consumers arrive at the main advertising page.”

- “Advertisements or promotional messages are deceptive if they convey to consumers expressly or by implication that they’re independent, impartial, or from a source other than the sponsoring advertiser – in other words, that they’re something other than ads.”

The last bullet suggests what is likely the main ethical issue with native advertising—feigned objectivity. In fact, the FTC understands well the moral rationale as it explains:

“Why would it be material to consumers to know the source of the information? Because knowing that something is an ad likely will affect whether consumers choose to interact with it and the weight or credibility consumers give the information it conveys.”

It’s like a new acquaintance inviting you for coffee “to get to know you better” and soon into your conversation, they start to ask your thoughts about cars while sharing their opinions of a particular make and several specific models. You’re surprised by the topic but support the discussion. Finally, near the end of your meeting the acquaintance reveals that they’re a car salesperson, and they ask if you’d like to schedule a test drive.

Unfortunately, some of us have experienced situations similar to this one, which felt uncomfortable because we want to know:

- When the context we’re in is a commercial one, i.e., we’re being sold to.

- When the person with whom we’re speaking is an agent of an organization or has some other financial stake in the product or company they’re describing.

There’s nothing wrong with a salesperson doing their job when we know who they are and what they’re doing. We expect them to tell us the good things about their products with little treatment of their weaknesses. Since, complete objectivity is not expected, we take what they say with a grain of salt.

In contrast, when talking with friends, family, or coworkers about products, we let down our perceptual guards and take what they say at face value because we believe they’re objective and unbiased.

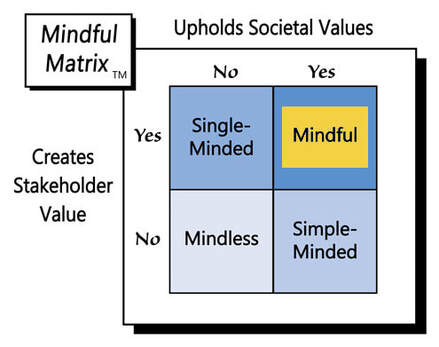

To be fair, not all native advertising deceives to the same extent. Some ads very clearly identify themselves as sponsored content, and they provide the exact content they promise, offering real value through useful information or worthwhile entertainment.

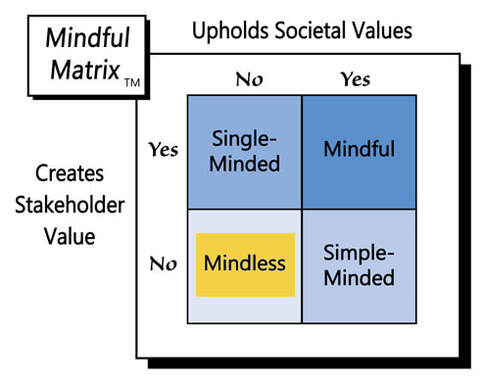

However, any ad that tries to trick people into taking steps they wouldn’t otherwise choose is on legally and ethically shaky ground. Relationships that start with a lie usually don’t last, which is why ads that deceive represent “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed