author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

The site of the showdown is the corner of 34th Street and Broadway, New York City, at the center of U.S. commerce. It’s there that Macy’s, which once boasted “the worlds’ largest retail store,” is taking what could be a final stand against the encroachment of Earth’s fastest-growing retailer, and one of nature’s most irrepressible forces: Amazon.

Macy’s has filed a lawsuit against Amazon, hoping to keep its close competitor from commandeering a 2,200 square foot billboard that adjoins Macy’s flagship Herald Square store. It’s a signage space Macy’s has leased for nearly 60 years.

The huge billboard, which features Macy’s iconic star and logo typeface set against the familiar bright red background, serves as a beacon for millions of pedestrians and potential shoppers as they walk north on Broadway and west on 34th Street. Millions more see the sign every November in countless camera shots during the retailer’s world-renowned Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Amazon, an organization that can send astronauts into orbit, is capable of just about anything, but how could even it endeavor to place its name on a billboard on the side of such a storied competitor’s flagship store?

Key to the controversy is the fact that Macy’s doesn’t own the building on which the billboard rests; the sign is actually attached to a small separate edifice situated just between the retailer’s massive 2.2 million sq. ft. store and the intersection. The owner of the tiny architectural interloper and its very valuable billboard is Kaufman Realty Corp.

With the contract it signed in 1963 expiring, Macy’s asked Kaufman to renew its billboard ad, but the company told its long-standing tenant that it intended to rent the space to a “prominent online retailer”—one who apparently has deep pockets and who most believe is Amazon.

Of course, both Macy’s and Amazon have physical stores and virtual ones; yet, Macy’s is in many ways the quintessential brick-and-mortar retailer while Amazon practically owns online shopping.

In a very real way, therefore, the billboard battle represents a titanic clash of competing marketing channels and business models, the results of which could impact consumer shopping behavior for years to come, as well as set important moral precedent.

Macy’s firmly believes that its loss of the advertising space, next to its flagship store, would be disastrous, as the suit it filed states, “The damages to Macy's customer goodwill, image, reputation and brand, should a 'prominent online retailer' (especially Amazon) advertise on the billboard are impossible to calculate.”

With net income that’s exceeded $1 billion for eight of the last ten years, Macy’s is doing well compared to many retailers, especially those that filed for bankruptcy over the last 18 months, e.g., Lord & Taylor, J.C. Penney, J Crew, Neiman Marcus, and Pier 1.

However, Macy’s profit margin for 2020 was a modest 2.9%. Amazon, in contrast, had net income of $21.3 billion on revenue of $386 billion, giving it not only much greater earnings but also a significantly higher rate of return—5.5%.

So, although Macy’s is not quite on the cusp, it’s certainly not operating from a position of power versus Amazon, and it truly can’t afford to see its flagship store, which it’s described as its “most valuable asset,” take a serious financial hit.

However, a hit on Macy’s Herald Square store and its effect on the future of retail is only one concern of the billboard battle: Amazon’s aggressive competitive tactic is also a breach of business’s moral bulwark.

Of course, Amazon has a right to buy any billboard it wants, but a key question is why the firm needs to buy that one.

According to Statista, there are over 340,000 billboards, or “big format outdoor displays,” in the United States. Just a ten-minute walk north of Herald Square lies Time Square, which has probably the greatest display of outdoor advertising in the world.

Granted, a sign in this spectacle of commercialism comes at a very high cost: between $5,000 and $50,000 a day, which could mean as much as $18.25 million a year. Still, that amount of money is almost immaterial to the one of the world’s richest companies.

As of December 31, 2020, Amazon’s balance sheet showed cash and cash equivalents of $41.2 billion. Even a $50,000-a-day billboard would represent less than half of one percent of those liquid assets (just 0.0445%).

So, if hundreds of thousands of large outdoor signs are available and Amazon can afford to rent any billboard it wants, why does it have to have the one in Herald Square that’s adjacent to one of its biggest competitor’s flagship stores?

It’s reasonable to infer an intent to attack the heart of Macy’s operations, to steal shoppers from in front of its landmark store, and perhaps even to embarrass the firm before its own customers.

Some might respond to such assertions of over-the-top aggression with, “That’s business,” or “Amazon is just being competitive,” or “The company is playing to win.” There’s a difference, though, between working hard to win and trying menacingly to make others lose. Unfortunately, Amazon’s billboard-buy seems like the latter.

Growing up, I loved to play sports and considered myself a pretty competitive person—I wanted to win and tried my hardest to do so. Although I didn’t like losing, I could tolerate it—it wasn’t the end of the world—especially if I played my best and the other person/team simply outperformed me.

By the same token, I never liked the idea of trying to sabotage or subvert opposing players’ performance. Instead, I thought, “Let them do their best, and I’ll do my best, and whosever best is better deserves to win.” I didn’t have to come out on top every time; I could ‘share the podium.’ Part of competing was knowing how to win and lose graciously.

In contrast, some individuals and organizations compete as if it’s all or nothing, and they have to have it all, all the time. They’ve no sense that ‘the market's big, so there’s plenty of business for everyone.’

Maybe it’s because of the holidays that this self-obsessed way of thinking reminds me of the Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life--specifically the film’s antagonist, the greedy and scheming Mr. Potter. Although he and his bank already own half of Bedford Falls, he won’t rest until it’s all under his control, not tolerating even a minor amount of competition from George Bailey’s small Building & Loan. No one else can win; he has to have it all.

My guess is that Mr. Potter would be proud of Amazon’s attempt to pry the Herald Square billboard lease away from Macy’s.

Macy’s is no real threat to Amazon, which can afford any outdoor advertising it wants and doesn’t need to have that specific sign. So, why go after it? It seems like Amazon doesn’t want anyone else to win; it has to have it all.

Macy’s lawsuit claims that all past and present agreements have prohibited the billboard’s owner from ever leasing the space to any other “establishment selling at retail or directly to any consumer.” If that claim is true and Macy’s is offering Kaufman Realty fair compensation for the lease, Macy’s has even more reason to believe its treatment is unreasonable.

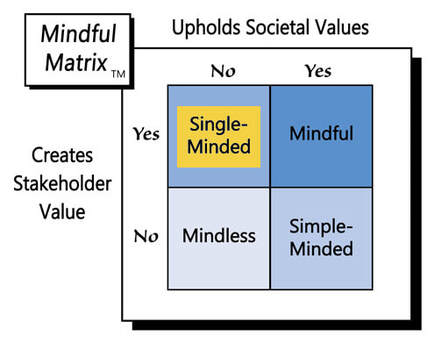

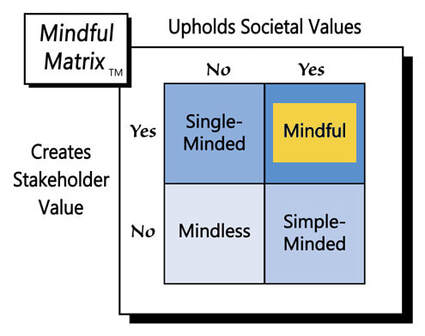

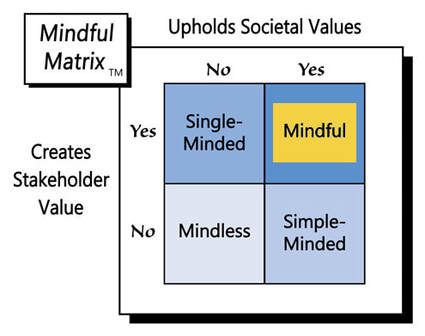

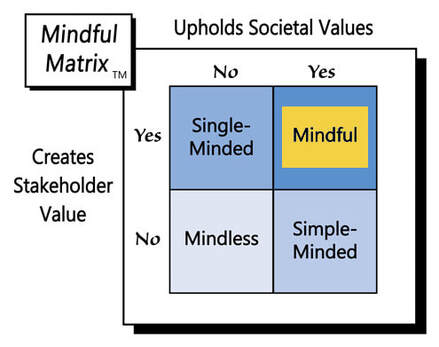

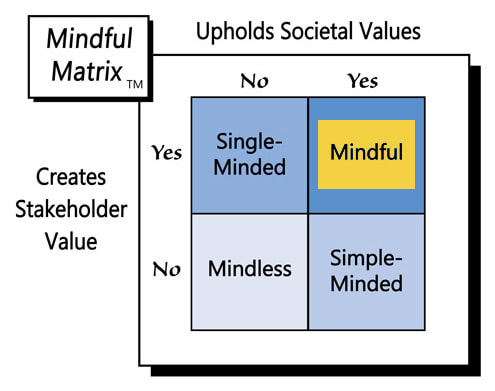

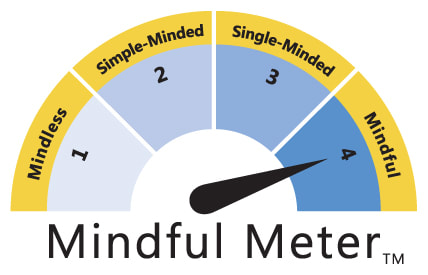

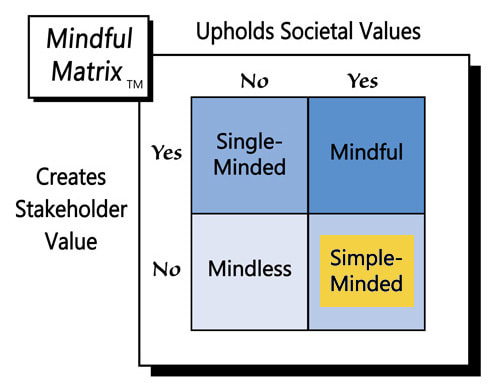

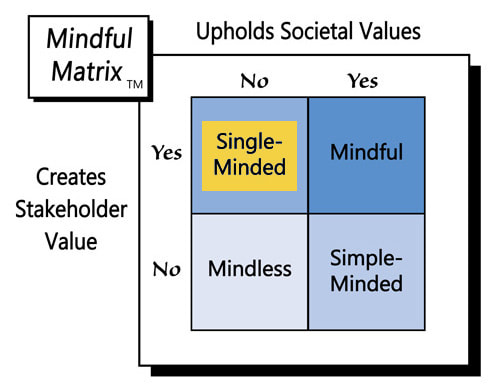

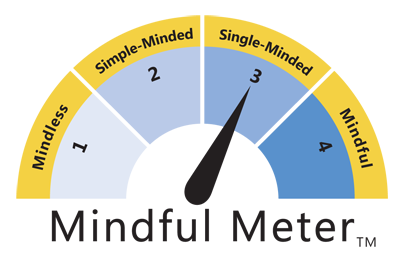

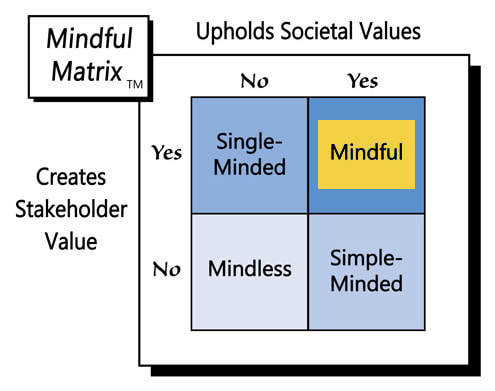

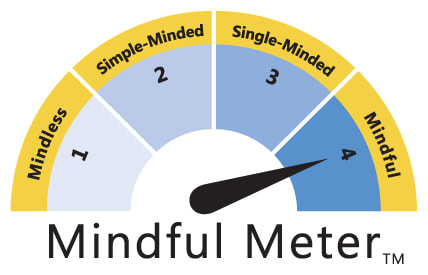

Competition is not only necessary, it’s desirable, as it both benefits consumers and sharpens industry rivals. However, when organizations like Amazon enlist predatory business practices, their strategies are a sign of “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed