It’s not surprising that people mess up. It’s also no wonder that organizations misstep; after all, they’re collections of people. What is amazing is when a group of very smart people puts their heads together and plans a misdeed, case in point: Volkswagen.

By now you’ve heard of the German automaker’s emissions scandal. In a brief, VW “cheated diesel emissions tests in the U.S. for seven years.” More specifically, the company programmed the software in many of its diesel vehicles to recognize when they were undergoing an emissions test and to temporarily reduce emissions in order to trick the testing instruments.

Why did Volkswagen cheat? As you might guess, cost was a consideration. The company chose to save money by not installing in its vehicles what most manufacturers use to reduce auto emissions: “a urea-injection system, often called AdBlue, which uses a chemical catalyst to make sure unburnt fuel doesn’t get into the exhaust.” Without AdBlue or similar technology, VW vehicles would pollute more than EPA emission guidelines would allow. So, the company decided it would be more economical to trick the testing equipment than to legitimately lower emissions.

How a small lab in West Virginia uncovered the scheme of one of the world’s largest automaker’s is another fascinating part of the story, which I’ll not elaborate here. The end result is that about 11 million vehicles appear to have been affected, which has caused VW’s stock price to plunge and has led to the resignation of the corporation’s CEO, Marin Winterkorn.

Although huge, the number VW cars involved is still dwarfed by Ford’s “Failure-to-Park” recall of 1980, in which the American automaker had to foot the bill for over 20 million vehicles whose transmissions inadvertently shifted from park to reverse. This defect cost Ford around $1.7 billion, but more significantly, it led to about 6,000 accidents, 1,700 injuries and 98 deaths.

In the case of these auto recalls, some mistakes appear bigger than others because of the size of the human toll and other damages. VW’s emissions scam caused no direct harm to people or property; still, the German automakers’ emission scandal will live in infamy for another reason—its malevolence.

Most other auto recall cases have been the result of negligence, i.e., people overlooking critical details because they failed to perform their work as carefully as they should. The ensuing consequences were very negative, but they were largely accidental. Even if there were attempts later to cover up the carelessness, the original error was unplanned.

VW’s case appears to be the exact opposite: employees weren’t careless; rather, they were precise in their intent to implement a defeat device that would operate outside the limits of the law. Volkswagen’s actions demonstrated criminal forethought and deliberateness that constitutes malice: “the intention or desire to do evil.” Or, to use a morbid metaphor of killing, while other car companies’ recall-related actions might represent unintended manslaughter, VW’s would represent premeditated murder.

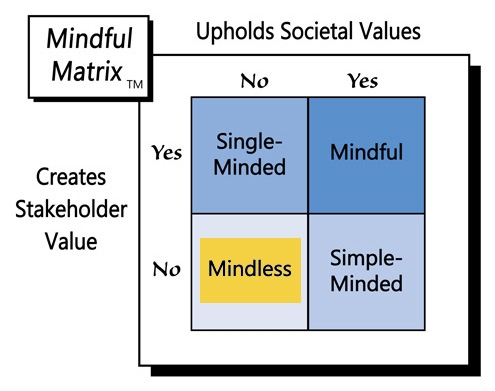

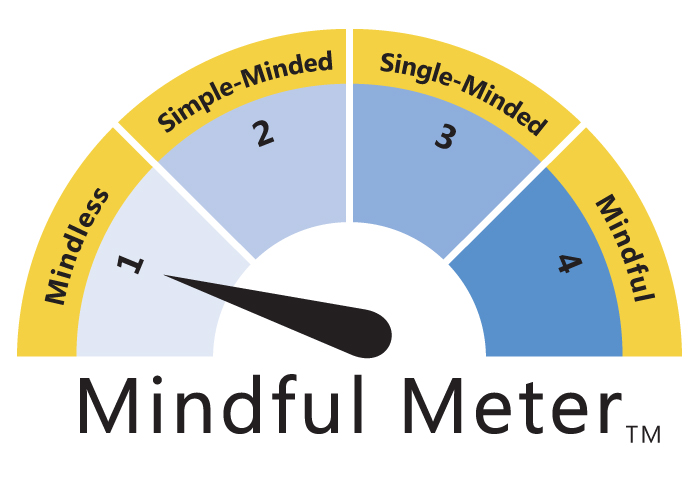

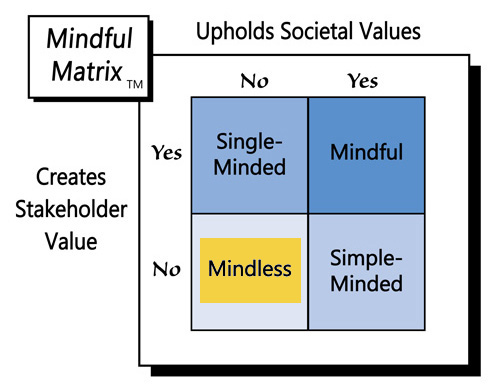

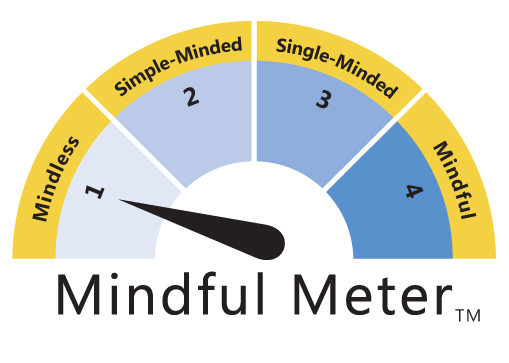

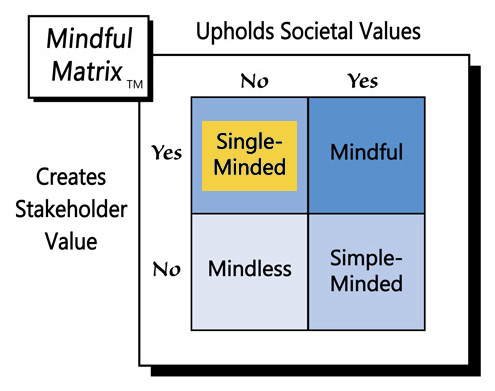

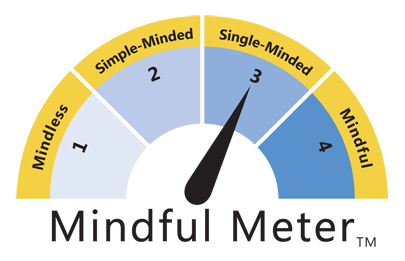

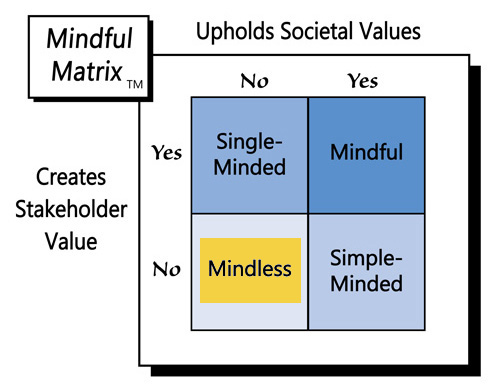

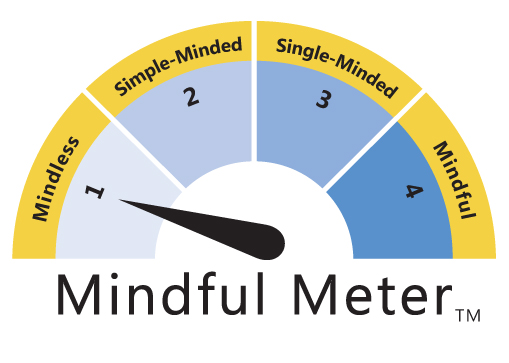

Volkswagen created considerable stakeholder value via the 11 million or so supposedly clean diesel vehicles it sold over seven years in the United States. Unfortunately, that value is rapidly eroding in the face of the company’s compromise of important societal values such as respect for the environment and fairness to consumers and competitors. The lowest reading on the Mindful Meter is “Mindless,” but VW’s actions suggest that perhaps there should be one level lower: “Malicious Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed