As companies have become increasingly skeptical of spokespersons’ abilities to keep their private lives under control, most endorsement contracts now include morals clauses, which offer advertisers an easy way out of their obligations when celebrities’ personal behavior tarnishes the reputations of their organizational underwriters. Such contract additions are legally expedient, but should companies exercise them? Doesn’t everyone deserve forgiveness?

Thanks to Lochte’s public drunkenness, vandalism, and deception involving the gas station incident in Rio, the twelve-time Olympic medalist has become a four-time released spokesperson. Speedo, Ralph Lauren, Gentle Hair Removal, and Airweave have all dumped the scandal-struck swimmer. Of course, Lochte is only the latest in a long line of celebrities who advertisers have dropped because of moral infractions. Other notable castaways include Lance Armstrong, Paula Deen, Bill Cosby, Tiger Woods, and even Lochte’s Olympic teammate, Michael Phelps.

Yes, in the wake of his unbelievable Rio Olympic performance, some have forgotten that Phelps had more than one moral meltdown that put him at odds with the law and advertisers. In 2009, the swimming legend was photographed using a marijuana pipe, which cost him the support of Kellogg’s. Then, in just December of 2014, he pled guilty to driving under the influence for the second time in ten years. Yet, despite these ethical issues, several sponsors have stuck by Phelps, including AT&T, Speedo, and Visa.

Maybe, then, it’s appropriate that a new sponsor has already decided to support Lochte, just a couple of weeks after his revelry in Rio. Lochte plans to appear in a series of print ads for Pine Bros., maker of “softish” throat drops. The campaign will be based on the theme of forgiveness, suggesting that Pine Bros. drops are “forgiving on your throat.”

What should we make of Lochte’s new endorsement deal? First, it’s hard to know the motives of Pine Bros. Perhaps the company is truly interested in encouraging compassion and helping Lochte bounce back from the bad behavior he has exhibited, not just in Rio, but also at other times. According to CNN, in 2005 and 2010, Lochte was cited three times and arrested once for crimes that included trespassing, urinating in public, disorderly conduct, and fighting in public.

Yes, everyone deserves to be forgiven, but forgiveness doesn’t mean that: 1) people escape the consequences of their actions, 2) offenders are enabled to repeat their behavior, or 3) others are encouraged to commit the same acts. Unfortunately, Pine Bros. sudden support of Lochte allows all three of these outcomes by: softening the financial hit on Lochte of the other lost endorsements, empowering him to continue illicit acts, and suggesting that such abhorrent behavior is acceptable for others. In addition, Pine Bros.’ fast funding, while an investigation of the incident is still underway, shows little empathy or respect for the Olympics, the nation of Brazil, or the owners of the gas station that Lochte despoiled.

But, isn’t Pine Bros. bold move good marketing? By linking with Lochte, the company is buying buzz that’s hard to match. If it’s true that any publicity is good publicity, Pine Bros. may realize some benefit from the sponsorship, but more likely the advertising campaign will collapse. The idea that the drops are “forgiving on your throat” is a weak unique selling proposition expressed in an awkward theme. In terms of AIDA, the use of Lochte may generate some attention and interest for Pine Bros., but the illogical pairing of throat drops and a scandal-ridden swimmer is unlikely to produce much desire for the product or action.

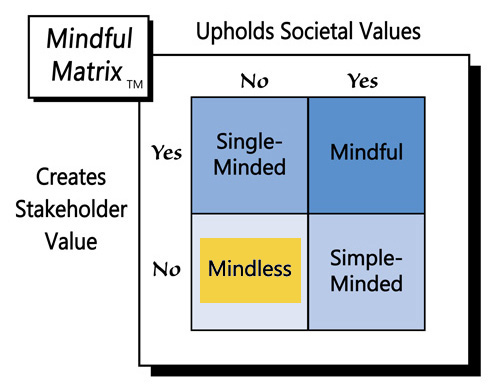

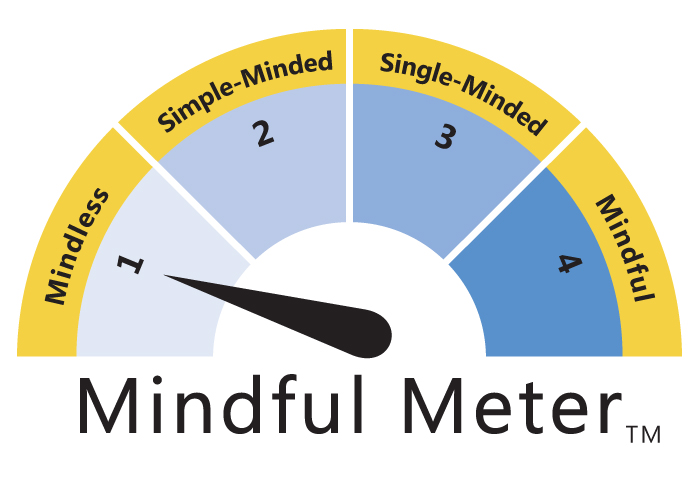

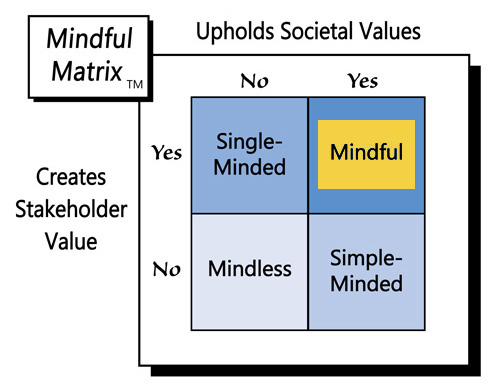

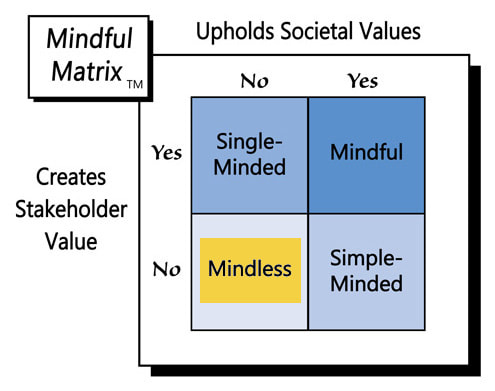

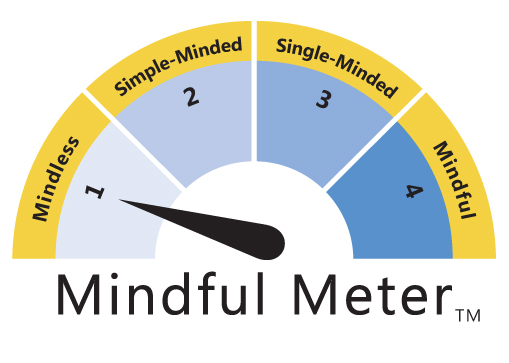

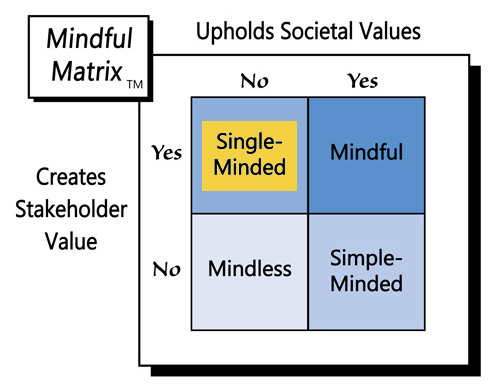

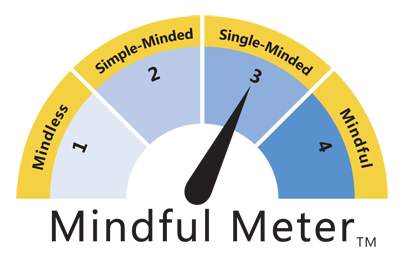

On the surface, Pine Bros.’ attempt to forgive Lochte seems commendable, but diving deeper into the sponsorship implications reveals weak values propelled by poor promotional strategy. As a result, Pine Bros. and Lochte have sunk to the level of “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed