This question raced to the front of many minds recently when Olympic steeplechaser Emma Coburn made U.S. track history, winning a bronze medal. Before Rio, no American woman had ever medaled in the event, but what Coburn did after the race was also remarkable—she took off her spikes, tied them together, and slung them over her shoulder as she strode along the track.

Although most runners don’t remove their shoes right after a race, what made Coburn’s action significant was not her bare feet but the New Balance logos on her spikes, which were suddenly in clear sight of spectators, the media, and their cameras. Coburn is an outspoken supporter of her sponsor, New Balance, so it seemed this atypical act was aimed at elevating her underwriter on athletics’ highest stage. Coburn also mentioned New Balance in a post-race press conference.

While it’s refreshing, in an age of entitlement and self-centeredness, to see true expressions of gratitude, Coburn’s post-race behavior likely ran afoul of the intent of Olympic promotional policy, specifically By-law 3 to Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter, which states: “Except as permitted by the IOC Executive Board, no competitor, coach, trainer or official who participates in the Olympic Games may allow his person, name, picture or sports performances to be used for advertising purposes during the Olympic Games.”

The reasons for this “blackout” rule are multifold. For one thing, the mandate aims to maintain the Game’s focus on the athletes and to keep the Olympics from becoming over-commercialized. There’s also a very practical purpose: The IOC needs to preserve the Game’s revenue stream, 90% of which “goes to the development of athletes and sports organisations at all levels around the world.” The promotional podium of the Olympic has limited space. If non-authorized advertisers try to stand atop it, the platform becomes overcrowded and sanctioned Olympic sponsors lose out.

A historic case of such party-crashing occurred twenty years ago at the 1996 Atlanta Games. Although Reebok put down a reported $50 million to become an official Olympic sponsor, non-sponsor Nike stole the spotlight with several unconventional marketing tactics: It outfitted legendary U.S. sprinter Michael Johnson with his now-famous golden Nike spikes, which were later featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated; it opened a grandiose “Nike Centre” right next to the athletes’ village; and it distributed flags to fans.

According to Adweek, it was Nike’s actions in Atlanta, more than anything else, that led the IOC and the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) to enact the very strict regulations that are in place today. Now companies that aren’t official sponsors are prohibited from saying “anything even vaguely evocative of the Olympics,” e.g., Rio or gold medal. Athletes, however, may be included in generic ads during the blackout time, provided that they don’t explicitly reference any of the Olympics’ intellectual property.

Nike became an authorized sponsor for the 2000 Sydney Games and since has had a long-standing official Olympic relationship, including in Rio where Nike has been a Team USA Domestic Sponsor, along with the likes of Citi, Kellogg’s, and Hershey. Ironically, it’s now Nike, which outfits many American Olympic athletes, that stands to lose from unauthorized marketing tactics, like those of Coburn for New Balance.

Olympic athletes are allowed to wear whatever brand they personally prefer when it comes to sunglasses, watches, and shoes, so Coburn was well within her rights to wear New Balance on her feet. By hanging her spikes over her shoulder, however, she transformed her footwear into advertising signage, which is out-of-step with IOC rules.

Maybe, though, Olympic promotional policy is unjust. After all, what would the Games be without elite athletes like Coburn, and how can athletes, particularly those hailing from non-paying sports, ever get that good unless someone supports them? Of course, the most likely supporters are companies, which need to receive advertising exposure in return. So, shouldn’t the IOC be more accepting of Coburn and other athletes who want to thank the firms that fund them?

The preceding point is a good one. Dependency does exist among the Olympics, the athletes, and their personal sponsors. However, that relationship does not provide enough reason to allow the Games to descend into advertising anarchy. As suggested in the Olympic charter, a primary appeal of the Games is that athletic accomplishment outshines commercialism—something that’s not always true in professional sports where venues are saturated with signage and some players’ jerseys even contain ads. In marketing terms, limited promotion for the Olympics is a powerful positioning tool.

Despite their wide embrace of advertising, even professional sports leagues like the NFL, NBA, and MLB know that official sponsors need to be protected, partly to preserve those lucrative revenue streams, but also to prevent competitions from becoming commercial mêlées in which every athlete advertises his/her personal sponsors on the same stage, at the same time. A classic example of the NFL’s restrictions came in 1986 when Commissioner Peter Rozelle fined Chicago Bears quarterback Jim MacMahon $5,000 for wearing an unauthorized Adidas headband.

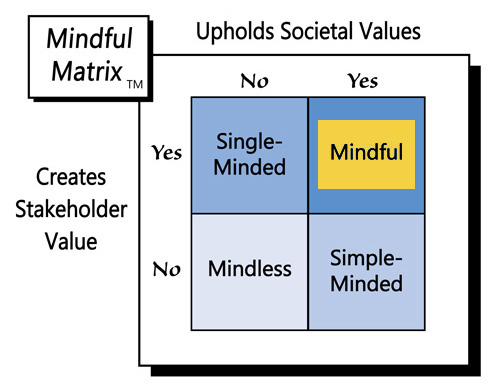

Yes, Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter likely costs athletes and their personal sponsors some income in the short-run, but the promotional policy is certainly in the best long-term interest of the Games and all its stakeholders, including consumers. Good, enforced rules are a key component of any successful sport. They’re also an important part of profitable and positive promotion, which ultimately makes them “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed