author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

The nation imploring intoxication probably isn’t one you’d expect — Japan. The world’s third largest economy and a leader in culture and industry has uncorked a contest called “Sake Viva” that asks citizens in their 20s and 30s for new ways to make and market alcoholic beverages. The term sake refers to both a Japanese rice wine and to alcohol in general.

Most of us are familiar with the risks of excessive alcohol consumption, which can lead to everything from disease (heart, liver), to poor mental health (depression, dementia), to social problems (broken relationships, unemployment), to DUI accidents (serious injury, death), all of which enact high financial and other costs on a country. So, why would Japan intentionally invite these expenses?

Ironically, the answer is money. As many governments have experienced, Japan is dealing with decreased tax revenue, partly because of an aging population and shrinking tax base but also because consumption of one of its most highly taxed products, alcohol, has been declining.

In the mid-1990s, alcohol consumption in Japan averaged over 26 gallons per person — a number that by 2020 dropped by about a third. What’s more, as younger Japanese are drinking less than their elders, the sobering trend seems likely to continue.

In only one year, from 2019 to 2020, tax revenue from liquor sales fell by $813 million, which was “the largest decline in three decades — and a cause for alarm for a government facing broad fiscal challenges.”

Given that in many countries, alcohol advertising is commonplace – on television, in magazines, and on billboards – why have many taken issue with Sake Viva on social media? The backlash seems to be based not so much on the message but who’s delivering it.

Ryo Tanabe, a Japanese man in his 30s, expressed this sentiment in an interview with NPR: “The fact that the National Tax Agency is doing this makes it a different story. I feel something is wrong with it. I understand they need the tax revenue, but I don't think they have to go this far.”

Tanabe’s reticence about his government advocating more alcohol consumption is easy to appreciate, especially given the increased individual and collective costs excess liquor can levy and the fact that we expect our governments to protect us, not put us in harm’s way.

But, if promoting alcohol is bad, should anybody be doing it? Claiming it’s okay for some to advertise alcohol but not others, seems a little like saying certain people can lie or cheat, but others shouldn’t. If something is wrong for one, shouldn’t it be wrong for all?

I have to admit that alcohol advertising is a difficult issue for me to approach objectively. My personal choice is not to drink, and I work for a university that maintains a dry campus. Over the years, I’ve also written several pieces about potential alcohol abuse by marketers, including:

Still, I have friends and family members who drink, and I respect their choices. I also remind myself and other Christians that Jesus’s first miracle was turning water into wine. There were likely then and there are now many people who subscribe to different worldviews and drink responsibly, in moderation, posing little or no risk to themselves or others.

There’s also scientific evidence that small amounts of certain alcohol, e.g., a glass of wine, hold some health benefits.

So, it’s possible to argue that it’s moral to consume alcohol in moderation, which suggests that it’s also acceptable to produce it for others to consume. But does this moral leeway also mean that alcohol producers can advertise their products?

As I’ve considered advertising, which is paid-for mass communication by an identified sponsor, I’ve often thought that if society allows production of an item, it should also permit its promotion, within reason; otherwise, a moral contraction handcuffs the producer — it’s very difficult for most products to succeed without advertising.

That doesn’t mean, though, that any advertising goes. A product like alcohol, in particular, shouldn’t be promoted to the wrong people (e.g., children), in the wrong places (e.g., near schools), or in the wrong ways (e.g., associated with athletic performance).

Another wrong way to promote alcohol or any product is to suggest its excessive use. Whether it’s food, or clothes, or entertainment, too much of even a good thing can cause people harm.

As suggested above, alcohol poses greater risk when consumed in excess than do most products, which brings us back to Japan’s Sake Viva campaign: Encouraging people to drink more, is tantamount to promoting drinking in excess, given that for most people the middle ground between current consumption and intoxication is likely very narrow at best.

On the other hand, alcohol producers can advertise their individual brands without necessarily encouraging consumers to drink more. The reason lies in the difference between primary and secondary demand, or demand for a product category versus demand for a particular brand.

In this comparative ad for Miller Lite, for instance, the beer claims to have “more taste and only one more calorie than Michelob Ultra.” Miller Lite isn’t encouraging people to drink more alcohol, rather it’s asking them to switch their beer purchases from its competitor.

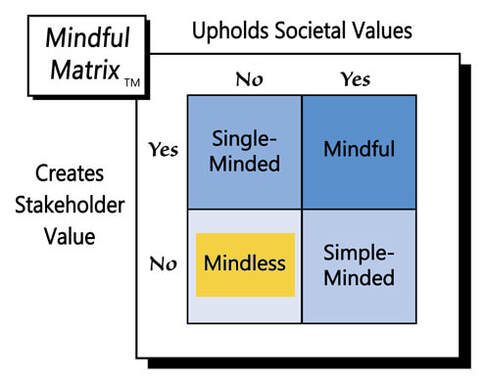

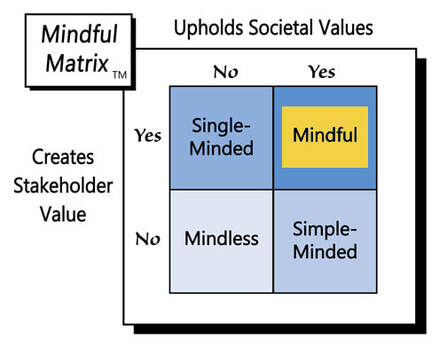

Given my personal consumption preference, I wouldn’t choose to promote alcohol, but I can understand how others might in order to support demand for specific brands. I can’t comprehend, however, how a country, tasked with protecting its citizens’ well-being, can promote more drinking. Encouraging excessive consumption of any kind equals “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed