The COVID-19-induced economic slowdown has derailed demand in most industries, leaving some businesses on the brink of insolvency. The U.S. Federal Reserve has promised $2.3 trillion in programs aimed at undergirding small and medium businesses; still, organizations of all sizes face immediate pressures to meet payroll, remit rent, and settle obligations with suppliers.

Many firms find themselves beholden to creditors like never before. While simply dismissing others’ debt may sound nice, such kindness cuts against the very grain of capitalism: Companies can’t remain competitive and profitable by giving away their goods and services. It may sound callous, but isn’t it just good business to forgo forgiveness?

Among the many hats I wore while a partner in our family’s promotional products company, was that of debt collector. At times, I would pick up the phone and call customers who had invoices that were 60, 90, or more days overdue. It wasn’t a job I enjoyed, but if enough of that revenue remained outstanding, it would take a significant bite out of our small business’s bottom-line. Although I worked to keep the conversations amicable, I wasn’t calling to offer forgiveness.

Fast forward a couple of decades—As I watched the April 9, 2020 installment of CNBC’s Squawk on the Street, the show’s often insightful and easily excitable Jim Cramer became uncharacteristically subdued while considering the pandemic’s unprecedented economic impact. In order to battle through the shared struggle, he recommended that businesses offer each other financial “forbearance.”

How surreal to hear the former hedge fund manager of Mad Money fame, who aims to help ordinary people understand the stock market and invest profitably, offer business advice that appeared tantamount to fiscal heresy. Had the Mad Money host gone mad? Or, has a time come when companies should be extending financial forgiveness?

To answer these questions, it’s important to differentiate forgiveness from forbearance. These definitions of the two verb infinitives seem especially relevant:

So, my earlier conflation of the two terms was somewhat misleading. While any forgiveness naturally includes forbearance, forbearance does not necessarily involve forgiveness. For example, a landlord can choose to forgive a month’s overdue rent, i.e., never collect it; or, he/she can forbear, i.e., give the tenant more time to pay.

In the Squawk on the Street segment, Cramer did aptly apply forbearance, suggesting that firms should be patient with their debtors. At the same time, he didn't preclude forgiveness, i.e., if a company can afford to reduce or cancel a specific debt, even better.

Such recommendations prompt two more important questions: Who exactly should forbear or forgive and why? The following story may offer answers.

The owner of a small grocery store was many months overdue on a $1,000 invoice from a large produce supplier. Unable to pay, the store owner begged his creditor for more time: “Please be patient and I’ll pay the bill.” The produce company owner felt sorry for his customer, so he told him, “It’s okay; we’ll cancel this invoice. You don’t owe us anything.”

The same day, a regular customer, who was recently out of work, came into the grocery store and asked the owner. “I’ve been shopping here for years and just lost my job. Could I get $10 worth of food to feed my family tonight? I can pay you tomorrow when my unemployment check comes.”

The store owner berated the customer: “Get out of here! I’m not running a charity!” When the produce supplier heard about the incident he was enraged. He phoned the grocery store owner: “I cancelled all of your debt. Why couldn’t you show some grace to one of your customers?”

Some may recognize this story, which is a modern paraphrase of the biblical parable from Matthew 18:21-35. Whether two thousand years ago or now, the moral is the same: We all should show grace to others because others show grace to us.

Over the past month, that point has been ‘brought home’ for me literally, as the pandemic has moved virtually all of higher education online. My house is somewhat unique in that in one upstairs room there’s me, sometimes asking my students for patience as I adapt to teaching college courses online. Meanwhile, down the hallway our son is taking classes from a different college, and his instructors are dealing with similar challenges.

As a college professor and the parent of a college student, I’m both a supplier and a consumer of higher education services. If I’m going to ask my ‘customers’ for forbearance, the least I can do is extend similar forbearance to our family’s ‘educational service provider.’

Life’s winding paths often lead to unexpected outcomes. Earlier I mentioned the collection phone calls I made decades ago for our family business. I can no longer remember any of the overdue accounts I called, except one: A company I had never seen that was located about 80 miles to the south that sold/rented lawn and excavating equipment.

I recall this account because it took what seemed like forever until I finally got to talk with the owner and kindly implore him to pay several long-past-due invoices. Significant interest charges had accrued, but I told him, “Just pay the original amounts, we’ll forgive the interest,” and he did.

I also remember this account because after we sold our family business and I entered higher education, our family happened to move within a few miles of where that business is still located. Now, I’m occasionally one of its customers.

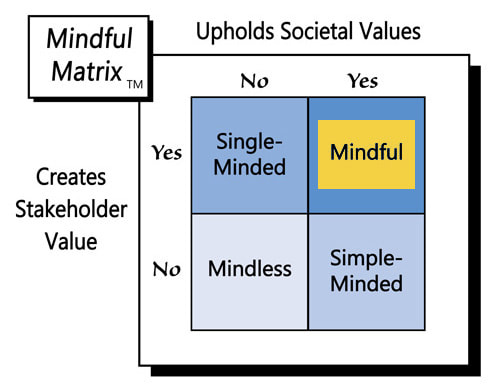

As flawed people who work for imperfect organizations, we all need to extend and receive forbearance at times, especially during a crisis. That doesn’t mean enabling those who take advantage of kindness, nor does it preclude going a step above and beyond to forgive an obligation entirely. A healthy balance of forbearance and forgiveness is good for business and makes for “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed