As an educator, I wasn’t eager to tackle another big ‘grading’ project (I have plenty of others right now), but after pouring over the firm’s privacy-related webpages, I’m glad I did. I learned much in the process, and I believe there are several useful takeaways for others who have an interest in how Facebook manages our data.

Most of my analysis stems from Facebook’s Data Policy page, which describes at length the company’s approach to user privacy. This page also contains links to a variety of other pages that unpack specific components of the policy.

Here’s my evaluation:

Readability: "A"

We’ve all experienced contracts and terms of service that we can tell at a glance will be a ‘bear’ to get through, perhaps because of all capital letters or marathon paragraphs. Facebook’s formatting is much more user-friendly, which may seem like a small thing, but if people avoid reading the policy, what good is it?

The policy features short paragraphs, many with three sentences or less, prefaced by bolded headings, which help readers locate specific information. Likewise, the overall organization of material is clear and logical. For instance, several main headings, set in a larger blue font, delineate sections for answering: “What kinds of information do we collect?” “How do we use this information?” and “How is this information shared?”

Clarity: "A"

Organization and formatting are helpful, but they’re meaningless if we can’t interpret what’s said. Most of us have experienced the mind-numbing legalese that seems as if it were written to confuse and confound. Fortunately, Facebook uses language that’s much more accessible, and if technical terms that some users may not recognize are needed, the company explains the concepts. For example, here’s how the firm describes cookies:

“Cookies are small pieces of text used to store information on web browsers. Cookies are used to store and receive identifiers and other information on computers, phones, and other devices. Other technologies, including data we store on your web browser or device, identifiers associated with your device, and other software, are used for similar purposes. In this policy, we refer to all of these technologies as ‘cookies.’”

Sometimes, however, even a clear explanation is not enough. In those instances, Facebook goes a step further by providing specific examples like the following one to describe how it shares data with third parties:

“We may tell an advertiser how its ads performed, or how many people viewed their ads or installed an app after seeing an ad, or provide non-personally identifying demographic information (such as 25 year old female, in Madrid, who likes software engineering) [emphasis added] to these partners to help them understand their audience or customers, but only after the advertiser has agreed to abide by our advertiser guidelines.”

Ease of Use: "A-"

Given that Facebook’s business model is based almost entirely on managing user-provided information, it’s data policy is inherently complex, which makes it all-the-more important that users can easily find the information they want and make changes to fit their personal preferences.

The company facilitates those objectives by making ample use of hyperlinks to other pages, like this one for advertising preferences, which allows users to better understand and manage the ads they see. Facebook also has programmed a decent amount of flexibility into data-related settings. Similar to the previous example, users also can determine the specific information they’d like to keep private vs. make public through means such as managing their Public Profile and using the Activity Log tool.

In addition, Facebook allows users to delete their accounts whenever they wish, or deactivate them temporarily. With those options, however, comes an important caveat from the company: “Keep in mind that information that others have shared about you is not part of your account and will not be deleted when you delete your account.”

Facebook’s ease of use slips somewhat when it comes to reporting others’ objectionable content. On its webpage “Details on Social Reporting,” the company says, “We encourage people on Facebook to use the report buttons located across our site [emphasis added] to let us know if they find content that violates our terms of use so we can take it down.” However, no such buttons are readily visible. Instead, the intended option for such censure appears to lie under each post’s three-dot drop-down menu under the somewhat ambiguous selection “Give feedback about this post.”

Transparency and Thoroughness: "B+"

Brevity is a virtue, but that benefit is lost if there’s not enough information to adequately communicate a message. In many ways, Facebook does a good job detailing its multifaceted data policy. For instance, it identifies each type of third party with which it shares information about its users: advertising, measurement and analytics services, vendors, service providers, and other partners. Facebook also broadly describes the kinds of information these third parties receive and how they use it.

Along the way, the company provides links to other pages that contain more detailed information, such as advertiser guidelines, the kinds of information it collects, and how users can control the types of ads they receive. In addition, Facebook offers in its Help Center a “Security Checkup” and a series of security tips with links to additional resources such as password protection and antivirus software for Mac and Windows operating systems. Unfortunately, the Microsoft link is broken.

How could Facebook be more thorough and transparent? The company states:

“We do not share information that personally identifies you (personally identifiable information is information like name or email address that can by itself be used to contact you or identifies who you are) with advertising, measurement or analytics partners unless you give us permission [emphasis added].”

As a researcher, the notion that Facebook aggregates data and maintains individual users’ anonymity is reassuring. As a Facebook user, however, I’d like more explanation for the final part of the above statement: “unless you give us permission.” How exactly do we give Facebook permission to share “personally identifiable information,” where is it possible to view the permissions we have granted, and how can we rescind such permissions, if we want to do so? Similarly, Facebook’s data policy states:

“We transfer information [emphasis added] to vendors, service providers, and other partners who globally support our business, such as providing technical infrastructure services, analyzing how our Services are used, measuring the effectiveness of ads and services, providing customer service, facilitating payments, or conducting academic research and surveys. These partners must adhere to strict confidentiality obligations [emphasis added] in a way that is consistent with this Data Policy and the agreements we enter into with them.”

“Transfer information” seems like another way of saying ‘share data,’ which is reminiscent of the Cambridge Analytica debacle. Of course, Facebook adds that “these partners must adhere to strict confidentiality obligations,” but how exactly is that third-party confidentiality monitored and enforced? Perhaps the answer is ‘above our pay grade’ as consumers; yet, it would be comforting to know that new and more effective standards for accountability are in place that will help to avoid a similar Cambridge Analytica breakdown.

Conclusion

Along with the preceding assessment, it’s important to note three things:

1. We use Facebook for free. Since users don’t pay for Facebook, the social media platform needs to cover its costs somehow. Like most other media, it does so through advertising revenue. Advertisers aren’t going to foot the bill, however, unless they know who they’re reaching, hence the need to share at least some user data.

2. The purpose of Facebook is to share information. If we posted things on Facebook and no one ever saw them, we’d be upset. The very reason we use the platform is to share information. Granted, we may only want to share things with our friends or certain others, but in keeping with the prior point, ‘beggars can’t be choosers.’

3. Users enjoy a better experience when Facebook utilizes their data. Granted, we don’t want to be taken advantage of, but seeing ads for products we want or content related to topics we like are usually preferable to exposure to things that are of no interest to us. Such customization is possible because of the data we provide.

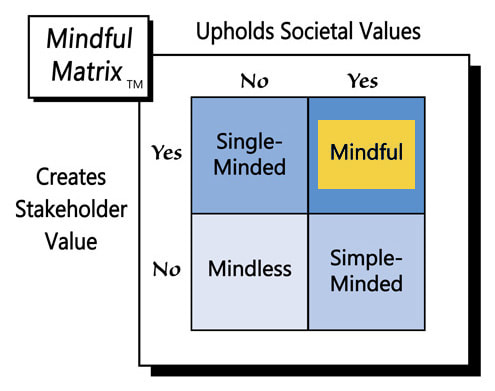

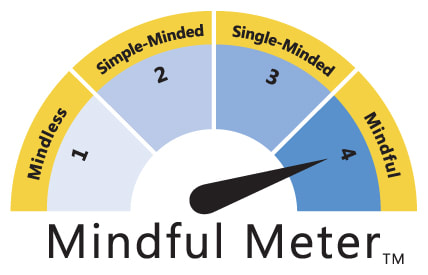

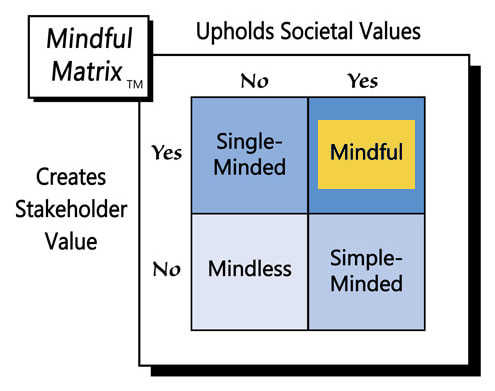

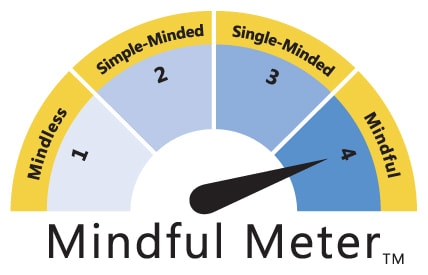

As the preceding analysis has suggested, Facebook’s data policy isn’t perfect. However, given the information-intensive nature of the company’s operations and the many different stakeholder groups who rely on that data, the company is doing a commendable job—one that warrants recognition as “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed