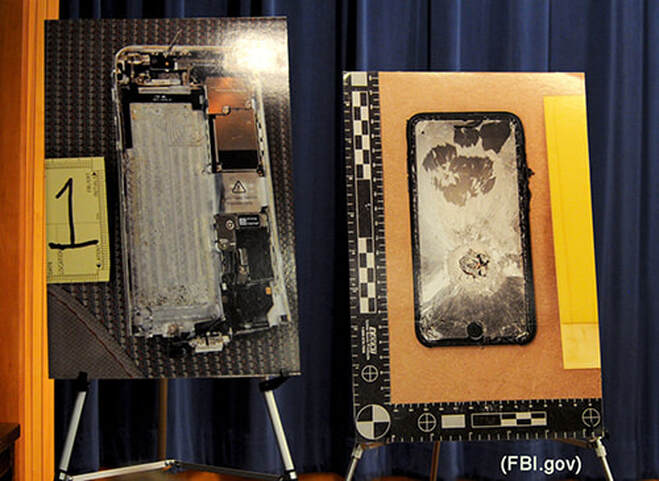

On December 2, 2015, Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik, opened fire at a holiday party in the Inland Regional Center of San Bernardino, CA, killing fourteen people and injuring 22 others. Because both terrorists died in a shootout with police, law enforcement was left wanting to know more about what motivated the attack and whether there were accomplices. So, the investigation turned to Farook’s locked iPhone:

“Agents wanted Apple to write a new operating system that would bypass the 10-attempt limit on the security code and other security measures. With this done, agents then planned to use a computer program to churn through the 10,000 possible passcodes until they hit upon the right one.”

Apple cooperated in other ways e.g., making engineers available, providing data, and trying to unlock the phone, but it refused the request to create a “backdoor,” to its phones, citing concerns over consumer security and privacy, as well as the precedent that such a concession would create.

Eventually, the FBI was able to gain access to the inside of Farook’s phone. The Bureau didn’t say how, but reports circulated that it paid Cellebrite, an Israeli forensics company $900K to hack into the device. In the end, however, “the FBI didn’t find any information they didn’t already have.”

Fast forward to the present, and we see how history often tragically repeats itself. Almost exactly four years after the San Bernardino shootings, Mohammed Saeed Alshamran, a member of the Royal Saudi Air Force, opened fire at the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, FL, killing three U.S. sailors and wounding eight others. Once again, the terrorist died in the attack, leaving behind two locked iPhones that the FBI can’t crack. U.S. Attorney General William P. Barr has explained the need to access the phones’ contents:

“It’s very important for us to know with whom and about what the shooter was communicating before he died. This situation perfectly illustrates why it is critical that investigators be able to get access to digital evidence once they have obtained a court order based on probable cause.”

Again, Apple has refused to acquiesce and build a backdoor to its phones. Barr has claimed that the company has offered “no substantive assistance” in the investigation. However, Apple, has rejected that characterization, saying “Our responses to their many requests since the attack have been timely, thorough and are ongoing.”

So, why isn’t the intelligence and security service of one of the world’s superpowers simply able to hack into a few smartphones? The most likely answer is that the data encryption, which Apple improved significantly with the introduction of iOS 8, is that good. Other explanations for the inaction are that “the FBI simply doesn’t understand (or won’t accept) Apple’s inability to help,” which had led to “Attorney General Barr’s larger anti-encryption push.”

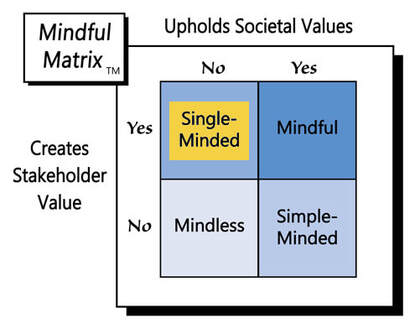

Notwithstanding concern for citizens’ safety, and perhaps even national security, in terms of marketing’s 4 Ps, Apple’s backdoor decision has profound impact for its “product,” i.e., the value users derive from owning very securely-encrypted iPhones and the company’s ability to continue to sell smartphones to those consumers.

No one wants his/her phone to be hacked, just ask Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, but does such personal protection outweigh a nation’s ability to fight terrorism and other crime? Clearly, the issue is complicated. Here are three related questions to consider:

- Would a backdoor mean less crime? Some may accuse Apple of averting justice by not providing an easy unlock for its phones, but less iPhone security could easily lead to more unlawful behavior. Although subsequent hacking would probably more often involve nonviolent crime like bank fraud and identity theft, there’s also reason to believe that users’ physical safety could be at risk by virtue of address information, GPS locations, and smart home apps found on many people’s phones.

- Would more easily-unlocked iPhones deter terrorism? Like most things in life, crime probably takes the path of least resistance. If one phone becomes easy for ‘the Feds’ to unlock, criminals will likely switch to another, and if every phone proves vulnerable, they’ll find other forms of communication. Also, if law enforcement is mainly accessing terrorists’ phones after the fact, they’ll just be more diligent in destroying them.

- Can governments be trusted? Although some individuals around the world and in the U.S. would answer this question emphatically, ‘No,’ most people appear to have a fair amount of faith in their local, state, and national officials. However, trusting anyone doesn’t necessarily mean giving them access to information or other sources of power that could prove too tempting to resist using unscrupulously. The founders of this country certainly had this principle in mind as often evidenced by various directives in the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Unfortunately, any one of us or a loved one might become the next victim of terrorism or another criminal act, possibly committed with the aid of an iPhone. However, providing easier access to the information inside our smartphones doesn’t appear to be a way of reducing that risk. In fact, such entry would likely introduce many more issues ranging from invasion of privacy to physical harm.

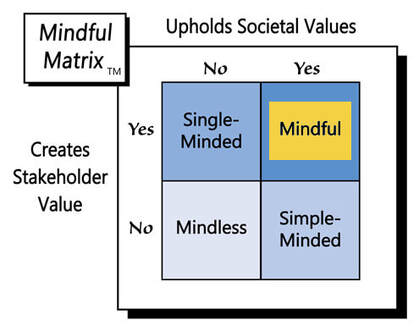

As the introduction of this blog post suggested and Apple affirms, “there is no such thing as a backdoor just for good guys.” If a smartphone maker creates one, it enables access to its users’ lives by anyone who can locate that entry point. By resisting pressure to comply and keeping its phones securely-encrypted, Apple engages in “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed