In 2017, the upscale British fashion label Burberry destroyed over $38 million worth of its own clothing, perfume, and accessories. BBC News says that over a five-year period, the brand scrapped products worth a total of about $121 million. Fortunately, Burberry announced last year that it would stop the ‘self-destructive’ behavior; although, it hasn’t said how it will handle the excess product. Unfortunately, Burberry isn’t the only brand known for trashing its own inventory.

According to Vox, other participants in the practice include luxury labels like Louis Vuitton, Michael Kors, and Cartier. However, even basic brands such as Eddie Bauer, Nike, and H & M, have been cited for incinerating unsold merchandise.

Why would any company destroy products it spent valuable time and resources making? Motives may vary for such a seemingly inexplicable practice, , but the main reason seems to be that high-end fashion brands, especially, need to preserve perceptions of exclusivity.

Some manufacturers, e.g., makers of snack foods and soft drinks, would like as much of their products sold as widely as possible. Certain other brands, however, seek to create an air of exclusivity in one of three main ways, either by not making the products available: 1) all the time, or 2) everywhere, or 3) for everyone.

For instance, although McDonald’s Shamrock Shake is available all over at a price that most people can afford, the ice cream is only sold for a limited number of weeks each year. Notwithstanding ever-increasing ticket prices, Disney positions its theme parks as entertainment for a very wide range of people, year-round, but it maintains ‘the magic’ by limiting the number of locations to just a few around the entire world.

Upscale fashion brands like Burberry, in contrast, place no real time restrictions on purchase of their products. Likewise, although they’re not as ubiquitous as MacDonald’s restaurants, these fashion retailers tend to have a decent number of brick-and-mortar locations. Burberry has about 50 stores in the continental U.S. in addition to its easily-available online storefront.

The main difference is that Burberry and similar luxury fashion brands aim for exclusivity by positioning their lines as prestige products sold at premium prices. For instance, a search for “all bags” on Burberry’s website returns a low price of $490 for a “Grainy Leather Card Case with Detachable Strap” to a high price of $2,750 for a “Medium Quilted Monogram Lambskin TB Bag.”

Of course, price alone excludes most people, who can’t afford to spend hundreds or thousands of dollars on a handbag, from buying Burberry; however, other positioning of the products also adds to their exclusive appeal: They’re not the purses we see shoppers carrying into the average supermarket.

‘Mousingover’ specific products on its website, reveals images of the kinds of people Burberry envisions owning its bags: ultra- stylish, impeccably-attired, young, affluent, runway-model types. That description probably doesn’t apply to most people reading this blog, nor does it apply to the person writing it, but Burberry doesn’t mind.

While MacDonald’s considers it a win if hundreds of millions of people eat its hamburgers, and Disney is delighted to have an even wider variety of people visit its theme parks, Burberry and other luxury labels don’t covet consumption of their products by the masses. Their brands’ allure is based largely on limiting availability to the relatively few people who can afford their products and who live the more lavish lifestyles associated with their use.

If somehow ‘average people’ began buying Burberry’s bags, the brand’s true target market would be turned off. Though its loyal customers may not articulate it, one reason they like Burberry is because very few people own the brand. Burberry banks on feelings of exclusivity, allowing its users to assert, "I own something that not everyone else has."

That brings us back to the issue of over-supply and what companies like Burberry should do when they’ve made too many handbags, hats, etc. In the past, Burberry has justified burning excess inventory, saying that it captured the energy from the burning, making the annihilation environmentally-friendly.

Unfortunately, though, “the energy that is recouped from burning clothing doesn’t come anywhere near the energy that was used to create the garment.” In addition, burning garments that contain polyester, which comprises about 60 percent of the fiber market, means the release into the air of harmful CO2, as well as chemicals often present in clothes.

Other ways firms have attempted to destroy unwanted products have included shredding and landfilling. Of course, these methods carry their own negative environmental impacts and fail to qualify as sustainable solutions.

Some may wonder why excess clothing can’t be recycled or donated. Mixed fiber cloth, from which many woven clothes are now made, makes recycling especially challenging, as do buttons and zippers, whose removal is very labor-intensive.

Others may ask “Why can’t surplus clothing simply be donated or sold at a discount?” For many companies, such product disposition ‘makes cents’ (pun intended), but not for high-end fashion labels. These brands can afford to take a hit on their enormous markups, but as mentioned above, they can’t accept dilution of their brands’ images, which occurs if their products fall into the hands of the less-than-modish masses.

So, what can fix this problem that pits environmental stewardship against brand equity? Unfortunately, there doesn’t appear to be a clear solution. In a 2018 interview with Vox, Timo Rissanen, an associate dean at Parsons School of Design and a professor of fashion design and sustainability at the school’s Tishman Environment and Design Center, provided a thorough analysis of firms’ destruction of excess product, but in the end, the best solutions he offered were for consumers to avoid impulse-buying and to instead purchase secondhand products.

Those are valid recommendations for you and me, but unfortunately they don’t really address prevention of the problem, i.e., what companies can and should do. I’m no fashion expert, and the following thoughts are admittedly undeveloped, but I’ll offer two possible ways to decrease the production of excess goods:

- Implement quick response processes: Fashion lead-times are often three months or more, making it challenging to match supply and demand. Spanish retailer Zara, however, has developed ultra-responsive production processes that allow it to move from product conception to consumer within a few weeks. If more brands would ‘follow suit’ (pun again intended), it might help to close the gap between what’s made and what consumers want to buy.

- Use artificial intelligence: Firms have employed data-based demand forecasting for decades, but even more accurate prediction is now possible through artificial intelligence in which machines learn from past experience and use algorithms to very accurately estimate future consumption. Such technology holds great promise for synchronizing supply and demand.

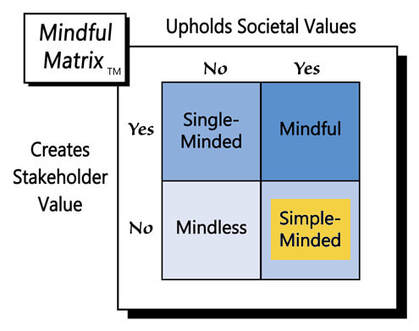

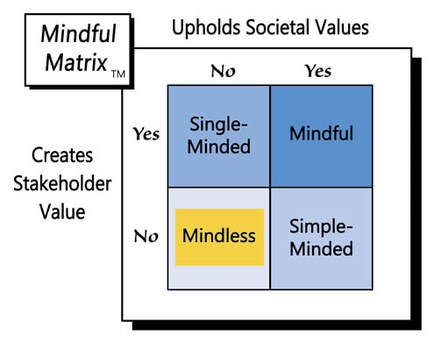

Burberry’s decision of over a year ago to stop burning its unsold clothes was certainly laudable and might be considered Mindful Marketing if the company were to implement some of the strategies mentioned above or take other consequential action. However, in the absence of a clearly conceived and communicated plan for managing excess inventory, Burberry’s announcement now seems like “Simple-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed