A couple of years ago, the world’s eighth largest retailer introduced “Amazon Dash,” featuring a handheld device that contained a barcode scanner and a voice recorder. The small smart stick communicated with the Amazon Fresh website and smartphone apps to help consumers more easily purchase over a half million products from the iconic internet marketer.

Although Amazon billed Dash as “Shopping Made Simple,” apparently it wasn’t simple enough. A little over a year later, the company introduced for its Prime members the Dash Button, which made ordering a variety of common household products like detergent and toilet paper as easy as hitting the snooze on your alarm clock.

Each Dash Button, which is just a couple of inches long, displays the logo of the specific brand to which it is tied. Consumers use their Wi-Fi connected smartphones to configure the specific product and quantity they desire, and they place the buttons near the locations where consumption occurs, e.g., on a washing machine. Then, when their supply starts running low, a press of the button sends an order to Amazon, generates an alert on the consumer’s account, and gets the product delivered to their door within a couple of days.

So, how have Dash Buttons been doing? By Amazon’s account, very well. Over a three month period earlier this year, the company saw Dash Button orders double in frequency from one per minute to two per minute, representing a total increase in orders of over 70 percent. This success has inspired the retailer to add 50 more brands to the list of those available with Dash buttons, including Campbell’s Soup and Cascade dishwashing soap. What’s even more interesting is that Amazon also has added certain toys to the collection, making it possible to press a button and receive a replenishment of Nerf darts and Play-Doh.

Despite the Dash Button’s apparent success, not everyone is singing its praises. One of those people is Mark Wilson who challenged himself to live with a Dash button in every room of his home. The experience left him cynical about Amazon and led him to conclude that although the concept may be good for the company, it signals a “futile” future for consumers. Here are several of his Dash Button concerns:

- There’s no immediate gratification. Although we’re used to pressing buttons and getting rapid results, products ordered via Dash Buttons usually take a couple of days to arrive.

- Product selection is very limited. Only 150 brands are available with Dash Buttons now, and each of those only has a small set of product options.

- People are paying to hang up advertisements in their own homes. Usually companies bare the cost of advertising exposure, but by charging consumers $4.99 for each Dash Button, Amazon has found a subtle way of flipping the business model.

- The products are generally expensive. Consumers gain convenience, but they forfeit the ability to use coupons or take advantage of special deals.

Although each of Wilson’s critiques has some merit, I don’t find the first two particularly compelling: There are other ways of satisfying needs for immediate gratification and larger selection, albeit, not as convenient as pushing a Dash Button. People wanting the former benefits have other purchase options.

However, Wilson’s suggestion of intrusive advertising is a very legitimate concern. What will our homes, workplaces, etc. be like if they become plastered with logo-laden buttons from Amazon and other companies? The commercial blitz may be unbearable.

Also concerning is Wilson’s fourth point, which he summarizes with the following statement: “The Dash button is an unabashed attempt to disconnect customers from the amount of money we're spending.” Although they’re not the most important things in life, buying and selling are significant human activities that shouldn’t be taken lightly. The money we have and the things we own impact our persons.

Yes, we make many routine purchases that don’t deserve much of our time or attention (e.g., bread, detergent, deodorant, etc.), but it can be dangerous if we treat other purchases too flippantly. For example, what lesson do children learn about the value of money when they observe it only taking the push of a Dash Button to get more Nerf Darts and Play-Doh?

As Wilson suggests, such monetary detachment can also happen easily for adults. Overspending on credit cards is partly a problem because paying with plastic is less painful for people than handing over cash. Studies have shown that people will buy more when using credit cards vs. hard currency. How much easier will overspending and compulsive consumption become if people start making substantial, non-necessity purchases with the push of a button? It seems like Dash Buttons could easily encourage reckless spending, undermining principles of stewardship.

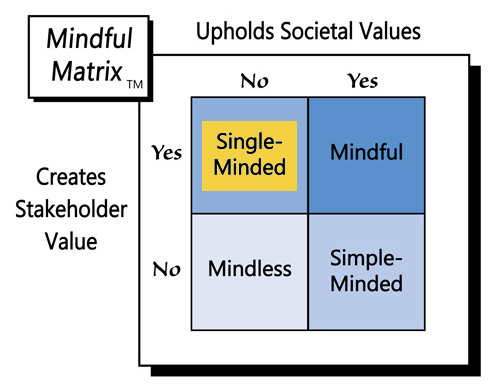

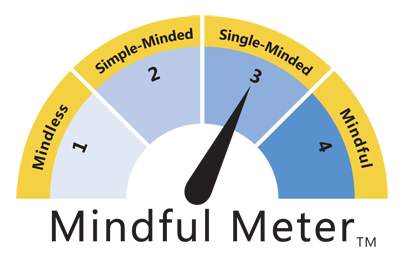

The growth of Dash Buttons suggests that they currently create stakeholder value for both Amazon and its users. However, broader societal concerns related to commercial intrusion in our homes and unbridled consumption make the buttons an example of “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed