by David Hagenbuch, founder of Mindful Marketing & author of Honorable Influence

Why do many of the products we wear each day vary so much in their sizing? The numbering systems they utilize should produce pretty consistent results across different suppliers; however, it’s not uncommon to find a pair of men’s 34” waist pants in one brand that are much bigger than the same size of another label.

Although men face some sizing snafus, what they experience pales in comparison to what most women endure in trying to find clothes that fit. Of course, women’s bodies come in many more shapes and sizes than men’s do, which makes it truly remarkable that designers claim to capture multiple anatomical variations in a single sizing digit, e.g., 8, 10, etc. A video by Vox provides a great summary of how such sizing came to be.

As if the single-digit system weren’t ambiguous enough, enter vanity sizing. It’s not surprising that many women want to wear smaller-sized clothes, given the emaciated models found in media and steady social pressure to be thin. Apparel makers recognize this desire, and some have decided to cater to it by revamping their sizing systems so their clothes are cut bigger. For instance, women who used to wear a size 6 can now fit into a 2, and those who had sported a 4 might don a double zero. The idea behind vanity sizing is to play upon people’s preference to think they’re thinner than they actually are.

Many people have long suspected manufacturers of vanity sizing, perhaps based on their personal experience, but is there proof that the strategy actually exists? Yes, the evidence is ample. For instance, a reporter for Vox documented her purchase of jeans of the same size from three different retailers, Forever 21, Topshop, and Zara, and showed how vastly different the widths were among them. Similarly, a writer for Esquire found that the actual waist measurements of men’s pants were sometimes as much as five inches bigger than their marked sizes.

If neither of those examples is convincing, checkout charts from the Washington Post which show how, over several decades, sizes have gotten smaller at the same time that people have become bigger. In 1958, for example, a size 16 fit a woman with a 29 inch waist, but in 2011, the same size fits a woman with a 36 inch waist.

So, there’s little question that many manufacturers have kept their sizes the same while making their clothes bigger in an effort to make consumers feel smaller, but couldn’t such vanity sizing be a good thing? In an age of body shaming and eating disorders, why not let people think they’re thinner than they actually are? In fact, a study in the Journal of Consumer Psychology found that vanity sizing was associated with positive mental imagery and improved self-esteem.

Unfortunately, any positive effects of vanity sizing are short-lived; instead, the strategy may be doing significant damage in other ways. Vanity sizing only works for so long. Eventually people realize that a size 4 is no longer as small as it once was, and they redefine what represents a thin size and what does not.

As suggested above, consumers also often experience frustration in dealing with significant size variations among manufacturers. It’s a waste of time to unnecessarily try on different sizes in order to finally find one that fits. The frustration can be even greater when shopping online, where realizing the right size might involve a series of shipments and returns.

Probably the biggest potential problem with vanity sizing, however, is the false sense of fitness it may give people. In the United States, nearly 69% of adults are either overweight or obese; almost 36% fall into in the latter category. With obesity comes increased risks for health problems such as high blood pressure, heart disease, high cholesterol, stroke, and some cancers.

Certainly people should consider their actual weight and their doctor’s diagnosis when determining their healthiness; however, it’s not unusual for people to use quick and convenient metrics like the fit of their clothing to decide whether or not they are overweight. Deceptively sized apparel does a disservice to consumers and can have physically damaging outcomes.

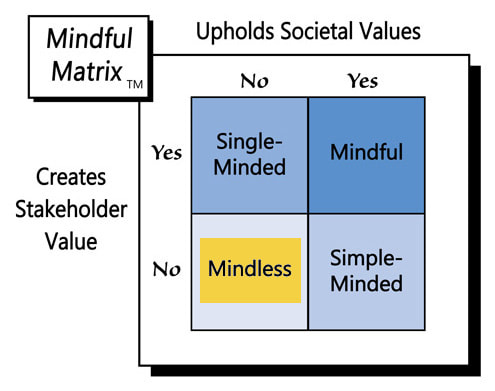

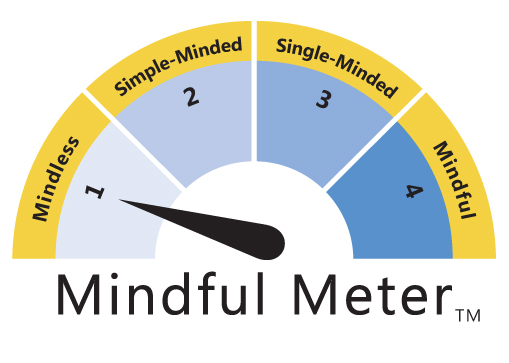

Given the detrimental impacts of vanity sizing combined with little promise of creating stakeholder value for marketers or consumers, there’s little question that vanity sizing measures up as “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed