Wednesday and Pugsley, seated at their lemonade stand: “Yes.”

Girl Scout: “I’ll buy a cup, if you buy a box of my delicious Girl Scout cookies.”

Wednesday: “Are they made from real Girl Scouts?”

This dark humor from the 1991 comedy movie The Addams Family may scare up a few laughs, but it’s actually a good example of the product name debate that has many people asking, “Does a burger have to be meat?” and “What makes milk, milk?”

Hamburgers are to blame for the most recent round of debate. A few weeks ago, Burger King started testing a “meatless Whopper,” a vegetable-based patty that contains heme, “a protein cultivated from soybean roots that mimics the texture of meat.”

Veggie burgers have been around for a long time, but thanks to business partner Impossible Foods, founded in 2011 by Stanford biochemistry professor Patrick Brown, the newest generation of vegetable patties not only taste much more like meat, they even bleed like beef.

Burger King isn’t the only fast food chain seeing potential in a plant-based future. McDonald’s has started selling a McVegan burger and vegan McNuggets in Europe, Del Taco will begin to offer meatless tacos, and White Castle and Red Robin are already serving meatless burgers.

For years, nutritionists have been telling us to eat less meat and more vegetables, so what’s not to like about the growing selection of ‘plant food’? The concern is that the new nomenclature, like the word meatless, confuses consumers.

For instance, Nebraska’s farm groups have lobbied for a more restrictive use of the word meat: “any edible portion of any livestock or poultry, carcass, or part thereof.” As one of the nation’s leaders in commercial red meat production, the state has a real “steak” in ensuring that consumers do not migrate away from ‘real’ meat.

Last October, Missouri became the first state to legislate that anything that doesn’t come from “harvested production livestock or poultry” cannot be called meat. That goes for lab-grown meat, like Finless Foods is creating by taking cells of dead fish, putting them in pretri dishes, and cultivating their division into edible protein.

The dairy industry has faced similar and even more far-reaching name-related challenges. For about the last two decades, producers of traditional cow’s milk have witnessed a surge in competition from the likes of almond, cashew, hemp, oat, rice, and soy “milk.” According to Mintel, dairy milk sales declined by 15% from 2012 to 2017, all while non-dairy milk sales increased by more than 60%, with almond milk grabbing a 64% share of the market.

It was in this context that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Commissioner Scott Gottlieb remarked that almond milk shouldn’t be called milk since “an almond does not lactate.” Shortly thereafter, the FDA opened a public comment period, inviting consumers and industry members to share their opinions on the milk-naming debate.

The FDA is justified in asking whether there’s been slippage in the “standards of identity” that ensure consumers understand exactly what they’re purchasing. That’s its job. However, the agency would do well to look back much further than the last 20 years, for instance, to 1626 when Francis Bacon observed that certain plants “have milk in them when they are cut.” Likewise, in the late 1700s, the Encyclopedia Britannica published that “the emulsive liquors of vegetables may be called vegetable milks.”

The fact is, people have been using the word milk to refer to similar-looking white liquids for centuries, if not much longer, from a wide variety of sources. Consider, for instance, milk from coconuts, as well as milk from other animals like goats and camels. Indeed, “nondairy milks [have] abounded in many other cultures across the globe.”

Furthermore, meat and milk are far from the only names that have been extended to describe a broader range of products. Take another common dairy product—butter. Peanut butter is entirely plant-based (no dairy), yet the FDA carved out an exception because the product's creamy texture resembles butter and because few people would be eager to purchase “peanut paste.”

It’s not to say that anything goes, i.e., that industries and companies can feel free to call their products whatever they’d like. However, names needn’t be limited to one narrow product category, provided that they serve at least one of the following legitimate functions:

- Identify who makes or sells the product, e.g., Avocados from Mexico, Starbuck’s

- State for whom the product is intended, e.g., Children’s Tylenol, Dove for Men

- Describe what’s in the product, e.g., wheat bread, whole grain pasta

- Identify key product features and/or benefits, e.g., fat-free yogurt, Sketcher’s Relaxed Fit

- Describe the product’s consistency, e.g., chunky peanut butter; Silk Soy Milk

- State the product’s intended use, e.g., Hamburger Helper; Liquid Plumber

Most importantly, neither the product category name nor the brand name should mislead a reasonable consumer. The labels listed above probably aren’t confusing to you or the vast majority of people who read them because marketers and our culture in general have done good jobs educating us about the words’ meanings

So, most Americans know “meatless” means a product does not contain meat. Likewise, as attorney Justin Person has said, “If a consumer is confused about the source of a product labeled ‘almond milk,’ then he has bigger problems than being confused about which milk to buy.” Reasonable people also know that Girl Scout cookies don’t contain Girl Scouts.

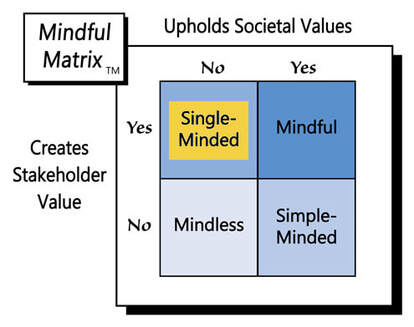

It’s not surprising that the beef and dairy industries want to preserve exclusivity for their product category names. However, given that consumers aren’t confused by broader-based naming and may even be helped by it, it looks like the two industries are doing little more than protecting their own livelihoods, which makes their name-related lobbying “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed