For the past year or more, TikTok has been on my radar screen, mainly because I try to keep tabs on what’s trending with the Gen Zs I aim to engage. Last fall, the topic of the hugely popular social media app came up in one of my marketing classes, which inspired me to ask the question: “Should I be on TikTok?” Several students immediately yelled “Yes!” while a seemingly equal number shouted “No!” I wondered if either group had my best interest at heart.

Still not a user, the app gained more of my attention throughout the spring as several of its most popular videos made their way into mainstream media and marketers began talking of TikTok strategies. Meanwhile, accusations of Chinese spying surfaced, and at least one U.S. firm asked its employees to remove TikTok from company mobile devices.

President Trump then threatened to ban TikTok, only to reverse course a few days later when global tech icon Microsoft indicated interest in buying the meteoric app. Most recently, the President signed an executive order that will result in barring TikTok from the U.S. market unless an American company buys the app, which has led parent company ByteDance Ltd. to sue the administration.

Each of these intriguing developments has kept me on the edge of my seat, wondering what will happen next, but no news sparked my interest as much as a blurb in an August 4th email blast from marketing tech guru Shelly Palmer, who stated that “TikTok is already near (or at) the top of the list of the most addictive [emphasis added] social media apps.”

Surveillance by a foreign state has seemed like TikTok’s biggest threat, but is Americans’ addiction to the app an even greater concern?

To answer this question, it’s essential to understand exactly what TikTok is, as well as what it’s so rapidly achieved—some of us above a certain age may need a primer. Steve Wright of Learn Online Video offers a nice overview of the app. He shares a few of its endless stream of 15-second videos, in which their usually young creators often dance and/or lip sync to popular songs. Wright describes the content, which is extremely varied, as “a smorgasbord of [the most] weird, creative, amazing, bizarre videos I’ve ever come across.”

Apparently many find the eclectic selection of “simple, goofy, irreverent” videos appealing. Since its launch in 2017, the app has been downloaded more than a billion times. According to Liv Benger, writing for Medium, “over 682 million people downloaded TikTok in 2019 and [spent] an average of 50 minutes a day” using it.

Those stats certainly suggest rapid growth and near saturation of specific population segments, but do they actually indicate addiction? Most of us know how hard it can be to put down our smartphones or other devices and stop checking email, playing games, texting friends, etc. For some people, those behaviors become compulsive, but do they really rise to the level of addictions?

According to Cornell student Niko Nguyen, the answer is ‘yes.’ In February, The Cornell Daily Sun published an essay in which Nguyen described that the main reason for his difficult decision to delete his TikTok account was that he had found himself “sucked into its addictive grasp.” He went on to explain why he believed TikTok is addictive:

“The app itself is designed to keep us glued to our screens. With most other social media platforms, the majority of content is derived from accounts that you follow. And although you can follow and “friend” a lot of accounts on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and Snapchat, there’s eventually a point where all the “interesting” content runs dry. With TikTok, that isn’t the case.

Nguyen’s explanation might sound like someone at a buffet who can't stop filling his plate because, “Everything tastes so good.” In that case, we’d probably tell the patron he needs to control his own eating; we wouldn’t blame the restaurant for his overindulgence.

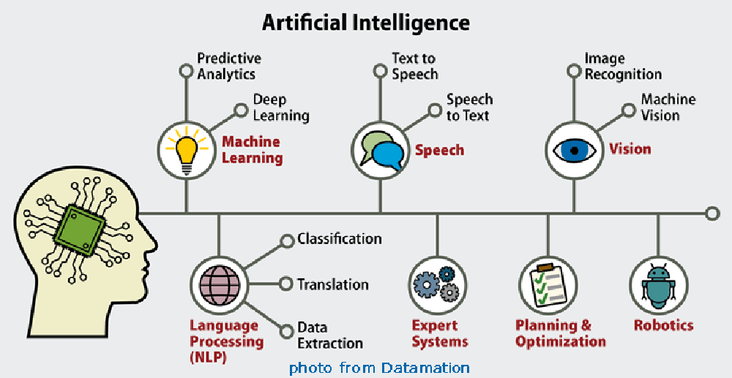

TikTok, however, isn’t the 'typical ‘restaurant.' It uses something that most other apps don’t, at least not in such a sophisticated way. Nguyen alludes to that something, which several others identify directly: artificial intelligence (AI).

Palmer, mentioned near the onset of this piece, is one person who claims AI is at the root of TikTok addiction. He says, “TikTok is a remarkably sophisticated AI model that literally tunes itself to your behaviors with a single goal: addicting you to TikTok.”

Others have further unpacked how AI might accomplish that objective. In a New York Times article, John Herman identified the technology underlying each TikTok user’s very personalized For You page as “an algorithmic feed based on videos you’ve interacted with, or even just watched.”

Unlike other social media in which users have a significant say in the content they receive by virtue of who they friend or follow and what those people post, TikTok’s AI notes what users actually like to watch, regardless who shared it, then sends them more of the same, making TikTok “more machine than man.”

A piece in Fixing Port supported the same assertion: “The TikTok algorithm can be blamed for this [addictiveness] to an extent. The algorithm sees what type of content you are watching (particular uploaders, particular genres, etc.) and then customizes the upcoming content to that liking.”

In The New Yorker, Jia Tolentino detailed her own ‘addiction’ to the AI-driven app:

“I was giving TikTok my attention because it was serving me what would retain my attention, and it could do that because it had been designed to perform algorithmic pyrotechnics that were capable of making a half hour pass before I remembered to look away . . . The algorithm gives us whatever pleases us, and we, in turn, give the algorithm whatever pleases it. As the circle tightens, we become less and less able to separate algorithmic interests from our own.”

In her article on Medium, Benger identified a psychological phenomenon, random reinforcement, that explains more precisely what TikTok users experience: Although not every video provides the same level of reward, like playing a slot machine, the periodic payouts come often enough that users keep pulling the lever/swiping their screen because the next clip could be a real winner.

The way TikTok employs AI does seem to put the app in a different category in terms of possible addiction. Whereas traditional methods of generating engaging content eventually run dry, the app’s AI-based video selection seems to know consumers better than they know themselves, allowing an endless array of just-often-enough, captivating content.

Notwithstanding these authors' insightful analyses of the app, two important and closely-related questions remain that none has appeared to answer:

- What exactly is addiction?

- Just because something is enjoyable, is it addictive?

Most people would likely easily answer the second question, ‘No,’ as there are many things that are very enjoyable to consume (i.e., eat, use, do) that are probably not ‘addictive,’ for instance: take-out from a favorite restaurant, a round of golf, a concert, ice cream!

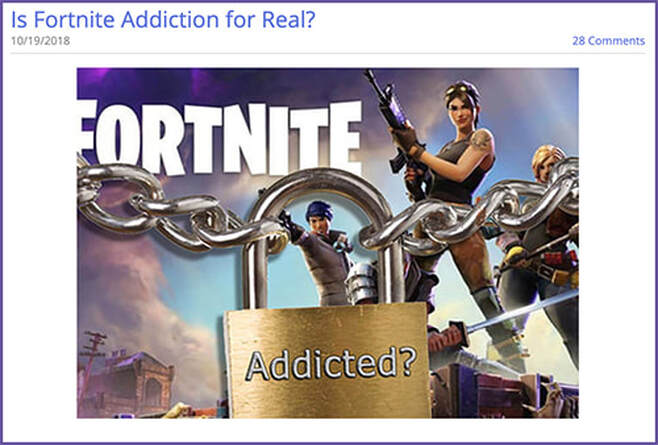

Over the years, I’ve often written about potentially addictive products, some of which have included:

In researching to write these and similar pieces, a few things I’ve learned are:

- People tend to play fast and loose with the word addiction.

- Genuine addictions tend to occur in relatively large percentages of the population, not with just a few people.

- There are specific clinical criteria for classifying substances and other things as addictive:

- a tendency to increase consumption

- a psychic dependence.

Although it’s common to hear people say things like, “That cake is so good; it’s addictive,” it’s unlikely that any of the clinical characteristics of addiction apply to eating cake. For these reasons, when I wrote the blog posts above, I concluded that numbers 1-4 are often true addictions, while Numbers 5-7, though problematic for certain people, really aren’t.

TikTok, seems to fit best with the second set of products as a non-addiction. That doesn’t mean that the app isn’t a time sink for some, or that it doesn’t present other potential problems. Most people, however, likely can control their use of the app by setting time limits and mustering some will power. Also, as Nguyen showed, it’s not that hard to close one’s TikTok account—it’s certainly much easier than dealing with a drinking problem or stopping smoking.

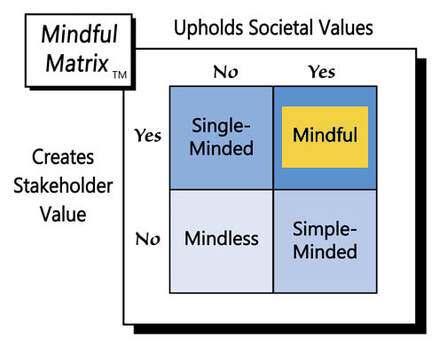

TikTok appears to provide its target market with inexpensive entertainment while also inspiring creativity and collaboration among users. Although some of us may not understand its appeal and there could be other issues with its content or use, at this point the app should be ‘swiped up’ as "Mindful Marketing."

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed