author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Most of us have now seen the clip of actor Will Smith striding onto the Oscars stage and striking award presenter Chris Rock across the face. The unimaginable physical altercation on Hollywood’s biggest night came because of a quip Rock made about the baldness of Smith’s spouse, Jada Pinkett Smith, who suffers from alopecia, a condition that causes complete hair loss.

Smith’s reaction was wrong. No matter the nature of the verbal offense, real or imagined, there was no reason for him to respond violently. Still, such condemnation shouldn’t stop anyone from asking whether Rock stepped over a line.

Of course, Rock is a comedian whose job is to make people laugh—a charge that’s particularly important when appearing at the Oscars, one of the most high-profile gigs a comedian can get.

Also, Oscars hosts and presenters have a history of lightly razzing celebrities in attendance. Legendary comedian and 19-time Oscars host Bob Hope was perhaps the earliest propagator of that tradition, making quips like this one during his 1971 monologue: “But this is a strange business. Just think, Frank Sinatra announced he was quitting show business and they gave him a humanitarian award.”

Billy Crystal, the second most frequent Oscars host (9 times), also had a habit of ribbing famous actors, as he did Clint Eastwood in 1993 for his role in Unforgiven: “Clint, of course, played that ruthless character, and you know he used those same tactics when he cleaned up that lawless renegade town of Carmel, California when he was the mayor there . . . It was Clint Eastwood who instituted the no crème brulee after 10:00 pm ordinance.”

Rock was himself an Academy Awards host in 2016, at which time he gave much of his monologue to highlighting the unsettling fact that there were no Black nominees at what he called “the White People’s Choice Awards.” He also took a jab at Pinkett Smith for boycotting ‘Oscars So White,’ suggesting it didn’t make sense for her to spurn an event to which she wasn’t invited.

Compared to the biting personal attacks for which insult comedians like Don Rickles, Lisa Lampanelli, and Andrew Dice Clay have been known, Rock’s comments may seem benign. Some might also suggest that humor is inherently controversial, i.e., some people will like a particular joke, while others will not.

It’s true that humor, like beauty, is in the ‘mind of the beholder’; however, there is a relatively clear line that individuals and organizations can avoid crossing to ensure that their jest about others isn’t injurious:

It’s usually okay to playfully point out the peculiar things that people do or say, but don’t joke about who they are.

Before offering some personal examples to support this suggestion, those who don’t know me well should understand that I’m far from a ‘wet blanket’ when it comes to humor: I love to laugh and endeavor to inject ad hoc humor into my classes, which I’ve found keeps students engaged, provides a brief reprieve from back-to-back-to-back classes, and lightens the load of weighty issues and complex concepts.

Other professors cite similar benefits. In fact, I recently read a Harvard Business article, “What educators can learn from comedians,” that offered empirical evidence for the third benefit above.

David Stolin, professor of finance at TBS education, collaborated with comedian Sammy Obeid, host of Netflix’s 100 Humans series, to create a variety of educational videos, some humorous and others serious. The researchers found that “when students were assigned humorous videos, they had consistently higher engagement and subsequent test performance.” So, among other things, humor helps learning.

I haven’t formally studied the same causal relationship, but I have done research on “playful teasing,” which suggests that good-natured ribbing helps build social bonds. I sometimes use that type of humor with my students, which brings me to my first personal example.

In one of my recent classes, a discussion about personal branding turned to ‘what coaches can do to encourage their players when they’re down.’ One of the students, who’s a college athlete, began to share her team’s current experience, saying, “It’s funny because two of my teammates tore their ACLs . . .” As she briefly paused to finish the sentence, I couldn’t resist interjecting some seemingly serious censure, “There’s nothing funny about that.”

Students, including the one who was speaking, laughed, and a classmate quipped, “I’m going to tell your coach!” The student finished her story and, of course, revealed that by “funny” she didn’t mean amusing but coincidental. People knew I was kidding because of the hyperbole of my comment, because we often joke in class, and because the students, all of whom I’ve had in other courses, know my penchant for dry humor.

The second example came a few years earlier when one of my students turned the comedic tables on me. As our class was discussing a case study about a particular west-coast-based restaurant chain, I showed a few pictures of my family and me, over the years, at various locations of the chain.

One student noticed something peculiar in the pictures and commented, “Dr. Hagenbuch, don’t you ever let your shirt out? Even on vacation, it’s tucked in!” I tried to argue that in a couple of the photos my shirt only looked to be tucked, but no one was buying it. We all had a good laugh, and shirt tucking became an ongoing joke for us.

Then, during the last class of the semester, I shared a specially made PowerPoint titled “Dr. Hagenbuch Untucked” that contained a dozen or more different family photos, all with my shirts outside my pants. The class appreciated the levity of the short slideshow and its homage to our inside joke. A couple years later, the student responsible for the original “untucked” playful tease, told me that our repartee was a highlight of his college experience.

The point of these examples is it’s very possible to laugh without shaming or otherwise hurting people, even when the humor is targeted toward one person. The key is a pure motive and playfully pointing out something silly the person inadvertently said (“It’s funny because . . .”) or did (shirts tucked in).

Rock’s Oscars jabs at Pinkett Smith failed both times to follow that protocol and instead took aim squarely at who she is. In 2016, his joke about her not being invited to the ceremony was a painful suggestion that she’s not a good enough actor. At the latest event, he made light of a physical condition that she cannot change and that likely makes her self-conscious.

For me, such humor is out-of-bounds; however, I wanted to hear the opinions of people who know much more than I do about psychology, sociology, and how Rock’s joke may have impacted not just Pinkett Smith but others. I reached out to two of my colleagues who teach in our university’s graduate program in counseling. They shared these reflections:

Dr. Leah K. Clarke, Director and Associate Professor of Counseling

“My own reaction to the joke was a resigned disappointment that women’s appearances and bodies, including black women’s hair, continue to be fair game for public discourse. Women and girls learn, almost from birth, that their bodies can be commented on, evaluated, touched, and utilized for other’s profit or pleasure. I’m not sure you could even count the number of songs that reference women’s appearances or specific body parts.”

“Pinkett Smith had previously shared about the source of her baldness, but even in doing so she acknowledged she felt she had to. Because otherwise the conversation about what was going on her scalp would happen without her. And she was right, Chris Rock and her husband had an interaction related to her appearance without her involvement or consent. The idea that her hair might be of no interest and nobody’s business doesn’t seem to occur to anyone.”

Dr. Sarah Brant-Rajahn, Assistant Professor of Counseling, School Counseling Track Coordinator

“Rock’s joke triggered the pain of many women and Black women, in particular, about ideals that are attached to appearance and hair as a beauty standard. I was surprised that such a joke would come from Rock, after his Good Hair (2009) documentary highlighted issues around Black-American women and the perception of their hair being acceptable or desirable.”

“As Pinkett Smith, like so many other women, attempt to boldly embrace their authentic selves and engage in self-love, they are met with ridicule, judgment, and shame when this true self does not align with societal notions of beauty. And to an extent, Rock’s joke and many like them can be viewed as bullying, as Pinkett Smith likely felt powerless to defend herself at a professional event, with an audience, and in a space that was being publicly recorded and viewed. There was a clear imbalance of power here where a male with a microphone and a stage demeans a female who does not have the same capacity to share her voice at the time.”

“While it is likely that Rock did not consider these implications, as he is a comedian and comedians make jokes about many people and topics, we would be remiss to not name and address the potential impact such comments have on girls and women, as well as the perpetual devaluation of them based on appearance.”

Beyond many specific truths, my overarching takeaway from both these experts’ assessments is that humor’s impact extends beyond the parties directly involved—a realization I’d also had through my research into playful teasing.

People often learn vicariously, i.e., from observing others’ firsthand experiences. Just as we can ‘feel’ that a stove is hot by watching someone else touch it, we can feel ridiculed when we hear or see someone deride a person who is in some way like us, e.g., race, body type.

Because the Academy Awards is broadcast to millions of people worldwide, Rock’s joke was at the expense of thousands of people with alopecia, not just Pinkett Smith. Furthermore, as Clarke and Brant-Rajahn have suggested, women and especially Black women were right to feel that their bodies and appearances were once more objectified for public consumption.

Their thoughts pinpoint the hypocrisy to which I alluded at the beginning of this piece. How can a society claim it’s concerned about bullying, shaming, and mental health, but be accepting of things like mean tweets, taunting, and caustic comedy? It's hard to understand why more aren’t alarmed by the troubling connections.

So, what does this analysis have to do with marketing? For any of us who aspire to make others laugh, how we handle humor becomes part of our brand, whether we’re an individual like Rock or an organization like GoDaddy, which is still trying to break free from its oversexualized Super Bowl ad humor more than a decade ago. The character of one’s comedy has long-lasting implications for one’s brand.

Just as the same medicine that helps people can hurt them if taken incorrectly, the ‘best medicine,’ laughter, can hurt people when its wrongly administered. It’s fine to playfully tease people for silly things they do or say, but we shouldn’t make light of who they are.

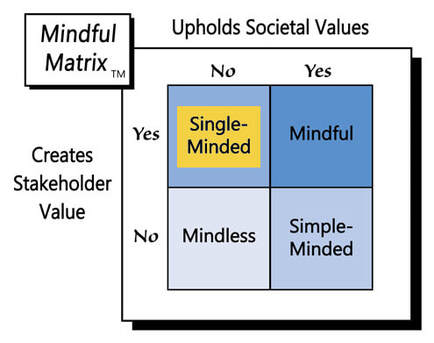

It seems that Rock’s stock has risen since the last Oscars, probably due to extra publicity he’s received, as well as sympathy from the slap. However, those truly deserving empathy are the ones Rock’s putdown humor belittled directly and by extension. The impact on them makes Rock’s ridicule “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed