author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Given everyone likes to laugh, people tend to appreciate individuals and organizations that add humor to their lives. Insurance companies like Aflac, Geico, and Progressive are well-known for luring consumers with levity via advertising slapstick, usually at the expense of their own corporate characters: Duck, Gecko, and Flo.

However, for five years, another company has taken a more aggressive comedic approach – Wendy’s, the ninth largest fast-food chain in America, has reasoned, ‘Why should we just laugh at ourselves, when we can laugh at you?’

To be fair, Wendy’s uses more than one type of humor. Like the insurance companies, the fast-food chain has characters – actors pretending to be Wendy’s employees – doing and saying silly things in what are pretty appealing ads. However, the company also uses comedy that very few organizations are bold enough to try – roasting others, even their own customers.

Wendy’s has long been known for using social media to spar with its burger competitors. Typical of the trash talk that Wendy’s aims at McDonald’s is this tweet from a few years ago: “Hey @McDonalds, heard the news. Happy #NationalFrozenFoodDay to you for all the frozen beef that’s sticking around in your cheeseburgers.”

However, those periodic jabs pale in comparison to what Wendy’s did in 2018, when it created its only holiday of sorts, “National Roast Day,” during which it invites individual and organizations to volunteer themselves to be roasted by the restaurant. Most recently, an animated version of its redhead, pigged-tailed namesake Wendy, the daughter of Founder Dave Thomas, imparts the insults.

Over the past few years, Twitter served as the platform of choice for most Roast Day putdowns, but this spring Wendy took her talents to TikTok and also tripled the length of the ribbing from one day to three.

A review of the video shorts shows that the roasts vary in their acrimony. Some are pretty benign, for instance:

- To a young woman wearing considerable eye makeup and applying lip gloss: “Hey, it’s the girl that walked the track in Cookie Monster pajamas during gym class.”

- To a young man who asks Wendy to roast his band’s music: “I’d roast your music, but just like everyone else on earth, I’ve never heard it.”

Other roasts are more acerbic:

- To a heavy-set young man: “I didn’t know someone without a neck could have a neck beard, but here we are. You learn something new every day.”

- To a thin-framed young man who recalls Wendy’s once wrapping “underwhelming” single burger patties in foil: “Should have expected a weak punchline from someone who looked like they’d lose an arm-wrestling match to a seven-year-old.”

- To a young man wearing sunglasses and a hat with a Pizza Planet logo, who speaks with a slight Southern accent: “Kids, this is what happens when you’re born in a truck stop bathroom.”

Of course, Wendy’s didn’t invent the roast. For that starting place, some point to 1950, the New York Friars Club, and roasts of comedians Sam Levenson and Joe E. Lewis. While the Friars Club has continued roasting one member a year since, others also have gotten into the act, namely Dean Martin’s celebrity roasts from 1974-1984, and Comedy Central. From 2003 through 2019, the cable channel aired one or two roasts a year of musicians, actors, and comedians, including David Hasselhoff, Charlie Sheen, and Roseanne Barr.

It’s unclear why Comedy Central stopped its roasts. Some on social media claim COVID killed the biting humor, while others note that the frequency of the channel’s roasts already had started to decline. There also were several very awkward exchanges along the way, including a roast in 2016 when instead of belittling roastee Rob Lowe, many of the roasters heaped brutal insults on fellow roaster and conservative commentator Ann Coulter. Retired NFL quarterback Peyton Manning compared her to a horse.

It might be naïve, but maybe Comedy Central’s cancellation of roasting had something to do with heightened sensibilities and introspection – i.e., What exactly are we doing here and what it’s greater social impact?

Understandably, some would want to push back on such criticism of Comedy Central’s specials and Wendy’s National Roast Day with plausible arguments like:

- Don’t take it so seriously; it’s comedy; it’s supposed to be funny!

- Everyone needs to laugh at themselves.

- Those people volunteered to be roasted.

Although each of those arguments has some merit, overall, they lack a good read of the room. In other words, they miss the bigger picture of what’s happening in our world, the tenuous turn society has taken, and how roasting provides poor but enticingly imitable examples of how people might interact with each other.

Even a casual observer can see that society has become increasingly divided ideologically and in other ways. Although such schisms have likely always existed, what’s new is the freedom and numerous ways people now have to berate not only individuals who think differently but also those who fail to act and look like they do.

Of course, social media has been a main conduit for that verbal abuse, allowing people to unfurl personal attacks with the protection of partial, if not complete, anonymity and to do so at physically, psychologically, and socially safe distances, i.e., without meeting their ‘adversaries’ face-to-face, learning their stories, and truly understanding them.

Many young people, in particular, seek validation from social media, allowing their self-image to rise and fall based on likes, shares, and comments, often from people they don’t know. Those fleeting rewards teach them what’s valued and motivate future behavior, often aimed at realizing similar temporary validation.

What’s more, people also learn social norms vicariously, or by observing others and seeing how society responds to their actions. So, if caustic criticism of a person gains thousands of likes on social media, thousands of others may reason, ‘I’d like to receive that kind of response; I think I’ll try that.’

There-in lies the real danger of Wendy’s roasts: They’re invitations to imitate derisive communication at a place and time when society is already deeply divided and young people feel stigmatized by social media.

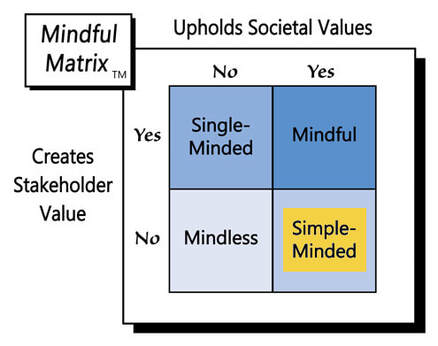

Fortunately, some other organizations not only recognize these serious societal rifts, they’re trying to remedy them. One such company is the global consumer goods producer Unilever. In keeping with its aim to be “purpose-led,” its personal care brand Dove has taken special efforts to battle the culture of criticism by doing things such as:

- Challenging TikTok’s bold glamour filter, which “sets unrealistic and harmful beauty expectations for girls and women.”

- Pushing for legislation to protect kids’ self-esteem, given the rise in mental health issues associated with social media use.

As someone who uses humor generously in his classes, I probably should be one of last people to criticize anyone who seeks to leverage the very legitimate value of laughter. However, roasting breaks the boundaries of what can be considered socially beneficial “playful teasing.”

From my 30+ years on the frontlines of customer interaction and college education, a little good-natured ribbing is not just tolerated, it’s often very desirable, provided the teaser:

- Already has a good relationship with those being teased

- Teases themself, or uses self-deprecating humor

- Pays many more compliments than teases

- Never teases about things that are sensitive or cannot be changed

- Doesn’t focus the teasing on just one or two people

Regrettably, Wendy’s roasts fulfill few of these criteria. Also, given the nasty nature of animated Wendy, the company’s website description of how its founder Thomas chose the logo is both ironic and sad: “He felt that the logo of a smiling, whole-some little girl with the name ‘Wendy’s Old-Fashioned Hamburgers’ would be the place where you went for a hamburger the way you used to get them . . .”

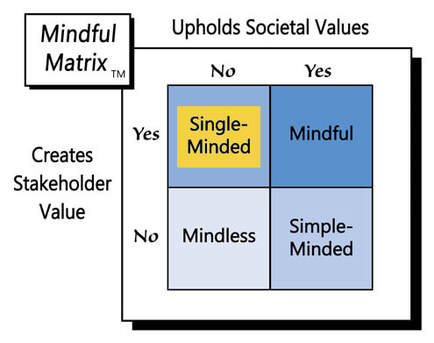

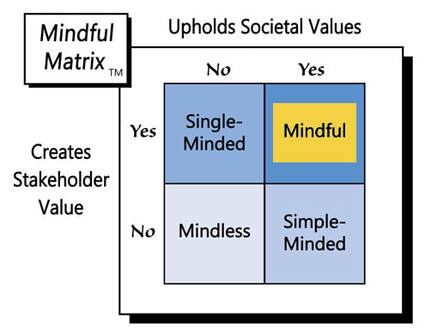

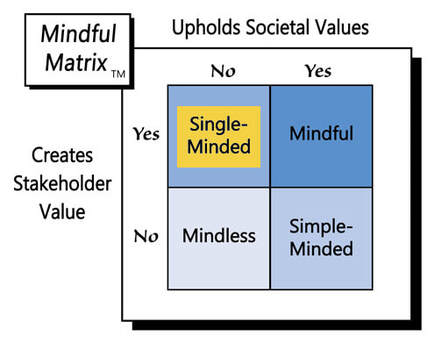

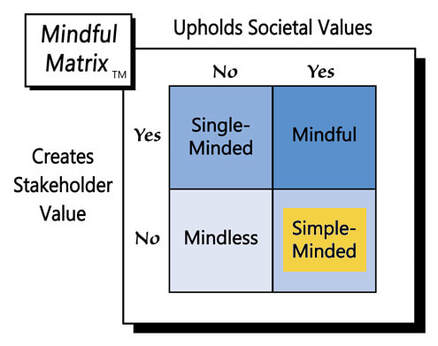

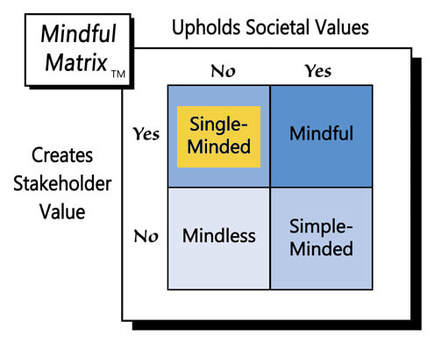

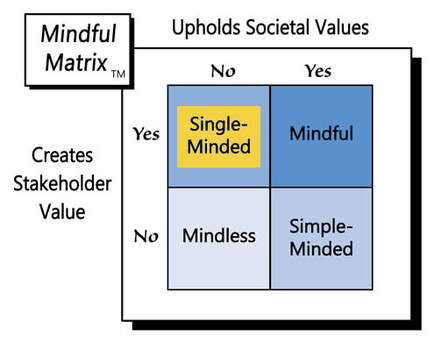

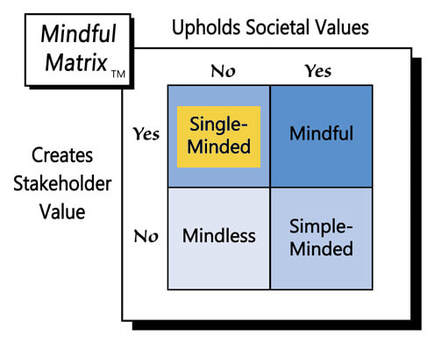

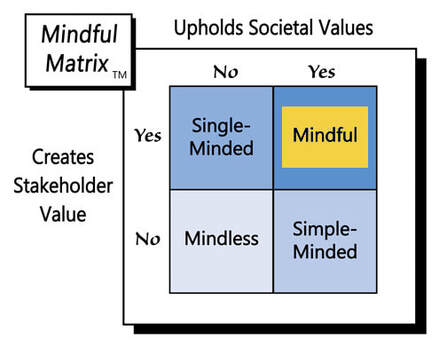

Given the expansion of its self-made holiday, the fast-food chain’s burger sales must be benefiting; however, the butt of the joke is a society that shouldn’t have to tolerate more divisiveness or attacks on individuals’ self-esteem. Wendy’s deserves kudos for wanting to make people laugh, but unfortunately it has cooked up a biggie serving of “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed