Eric decided to check the price for the same Amazon item, using a different web browser—one he had never used before to order from Amazon. Entering the website, he navigated anonymously to the item page, where his suspicion was confirmed: The price he saw was just $16.89, i.e., $2.05 lower than the price for the same item he had placed in his shopping cart minutes before.

Although most of us haven’t been so clever as to catch an ecommerce giant in apparent pricing hypocrisy, many of us probably have wondered whether Amazon and other online retailers were somehow taking advantage of us through increasingly-sophisticated pricing strategies. Responses to Eric’s Facebook post about the incident confirmed such concerns:

“I wonder if the price is also because you're a logged in Prime user in one and they compensate for some of the free shipping.”

“I’ve worked with some sellers on Amazon. They are a beast to deal with and it can really wreck a small business. And there is nothing the business owner can really do to combat their practices. They are the 8 million pound gorilla in the room.”

“I read [your post] out loud to my daughters, I thought it was so significant.”

“The exact same thing happened to me just recently. I was going to protest the increase in price over a year's time. What can we do?”

Frustration over similar experiences may lead to accusations of “price discrimination,” i.e., when a seller changes the price of the same product for different consumers. Generally speaking, it’s not fair to charge people different prices for the same item, but there are some seemingly legitimate exceptions, for example:

Quantity discounts: Buying a 36-pack of bottled water should be cheaper per bottle than buying a single bottle of the same water.

Good credit ratings: Individuals with better credit scores deserve lower interest rates on loans compared to those with weaker credit ratings.

New customers: The risk of trying a new business or products may warrant giving a discount to first-time buyers.

In reality, none of the preceding truly represents price discrimination because people can, if they choose, put themselves in the more favorable pricing position. For instance, they could: buy more bottles of water and store them, follow sound financial practices to improve their credit scores, or assume the risk of purchasing from a new company.

If Eric’s experience falls into any of these three categories, it might represent the last one. Perhaps because of his lack of history with the second web browser, Amazon pegged his subsequent shopping visit as that of a new customer and wanted to offer him an extra incentive for making a first-time purchase.

That explanation may be right, but it has some flaws, namely that companies tend to clearly communicate when they’re offering discounts for new customers; otherwise, loyal customers may locate the discrepancy, as Eric did, question the companies’ motives, and even become resentful: “I’ve given them my business for all these years; if anyone deserves a discount, I do.”

Chances are, Amazon wasn’t practicing any form of price discrimination. It’s more likely that Eric’s experience was a result of the strategy that many online retailers increasingly apply: dynamic pricing.

Dynamic pricing involves changing prices continually, based on prevailing market conditions, which includes factors such as consumer demand, purchase intent, and competitors’ prices, as well as company goals for customer acquisition, retention, and brand-switching.

If you’re thinking that dynamic pricing is a new phenomenon, you’re partially right. Sellers have lowered and raised product prices on the spot for millennia, based on factors as simple as weather conditions and buyers’ apparent interest.

Over the past 30 years or so, airlines probably have been the most common users of dynamic pricing, as they’ve perpetually adjusted prices to keep flights at or near capacity. To a lesser extent, those selling hotel rooms and tickets to popular entertainment events have done the same. Frequent historic fluctuations in gasoline prices also suggest dynamic pricing.

However, recent advances in digital technologies have really enabled dynamic pricing to thrive. For instance, from 2008 to 2010, the average time between regular price changes was 6.7 months. In the time period from 2014 to 2017, that average fell to 3.7 months.

Today, to implement far-reaching price change is no more difficult than a few computer key strokes, and it’s as easy as allowing a third-party software program, like an algorithmic repricer, determine when to make price adjustments and how big they should be.

Although Amazon, which reportedly makes millions of prices changes a day, is probably the greatest single user of dynamic pricing, it is far from the only retailer employing the strategy. Walmart, the biggest retailer in the world, has taken a remarkable step away from its long-standing ‘everyday low pricing’ strategy and embraced repricing software for its online sales.

Most other e-tailers are following suit. In fact, some predict that within 5-10 years, dynamic pricing will become so fine-tuned that “everything you buy will be based on personalized offers.”

So far this discussion has been about what has happened and will continue to happen with dynamic pricing. However, at the core of Eric’s experience is an ethical question: Should Amazon or anyone be pricing products this way? Or, as Nick Saunders, director of GlobalData Retail has said, just because something is technologically feasible “doesn’t mean it’s socially desirable.”

On one hand, it does seem like dynamic pricing puts purchasers at an added disadvantage. Companies already have a natural information-advantage over consumers since “knowledge is power” and every business knows more about its products and its industry than does the average consumer.

What’s more, sellers have always known more than buyers about when prices will change, so with dynamic pricing dramatically increasing the frequency of those deviations, consumers experience even more uncertainty while sellers gain greater leverage.

But, the digital age also has been a significant boon to consumers. For much of human history, sellers only had to compete on price with competitors physically close to them. Sears, Roebuck & Co. and other catalog retailers changed that situation somewhat. The Internet and ecommerce have turned traditional retail on its head.

Now people sitting in their living rooms use shopping bots to search products from retailers around the world, while shoppers in brick-and-mortar stores pull out their smartphones and ask for price matches in checkout aisles.

In addition, dynamic pricing itself has produced some benefits for consumers. As described above, the strategy does favor individual sellers in specific transactions; however, the fact that all sellers can easily alter their prices means they must compete more against each other on price.

In short, buyers and sellers both enjoy advantages in the digital age with dynamic pricing—a phenomenon that Eric recognizes, as he astutely reflects:

“This [experience] strikes me as another example of the free market and competition driving markets and pricing. As much as I might not like it, in my opinion Amazon as the seller has every right to offer its goods to me, their customer, at whatever price point they desire. And I, in turn, have every right to buy it or not!”

“Furthermore, there are times when I might willingly pay a higher price from Amazon because of other factors such as shipping speed or knowing that Amazon customer service is incredible for dealing with product issues or returns. From Amazon’s perspective, if they do the hard work of building loyalty with me, their customer, then it’s their privilege to offer me goods at a price point which might, at times, be higher than necessary.”

“The risk they take is that if I conclude that Amazon is no longer competitively priced, they might experience a decline in my loyalty. Which undoubtedly is another data point Amazon tracks about me! If they sense my purchasing loyalty is deteriorating, I suspect their pricing algorithms will work to win back my loyalty!”

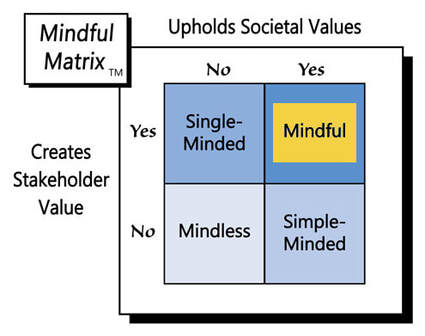

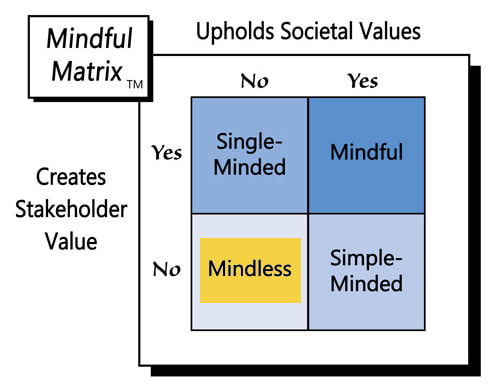

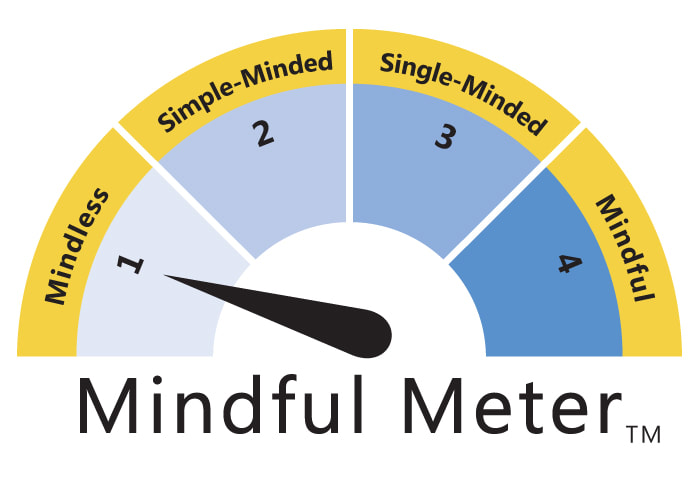

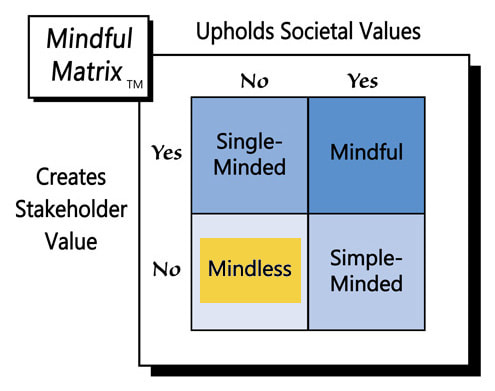

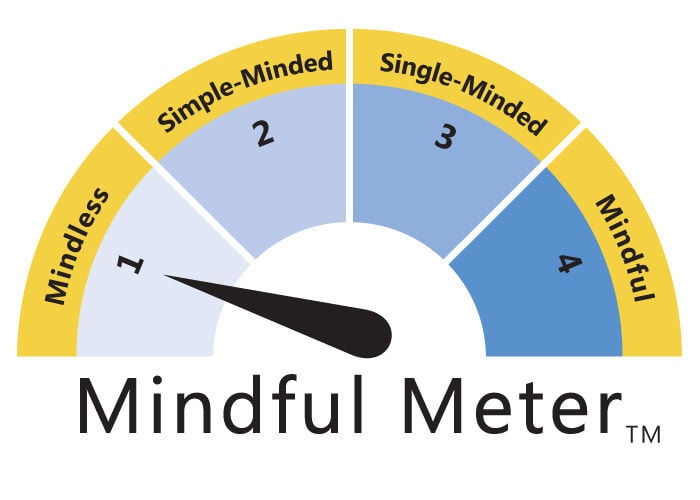

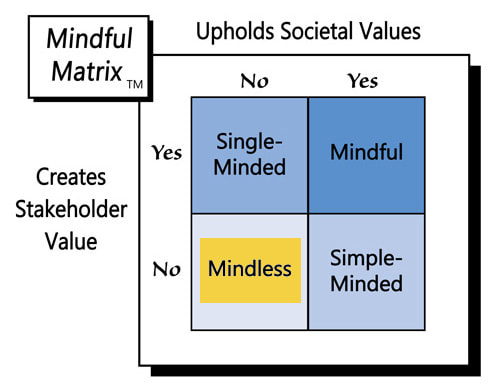

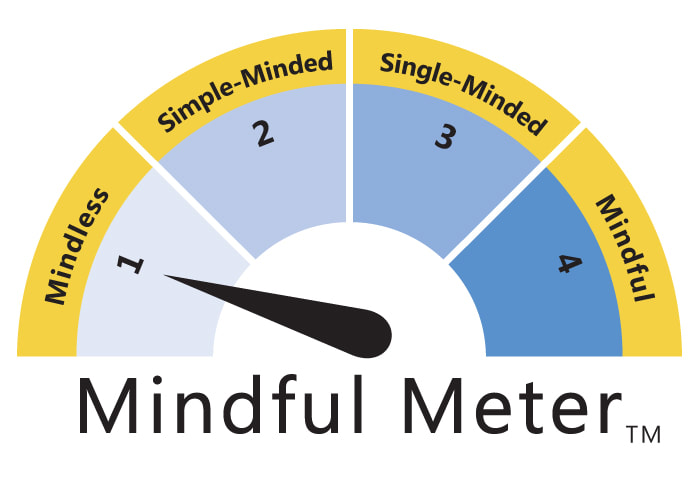

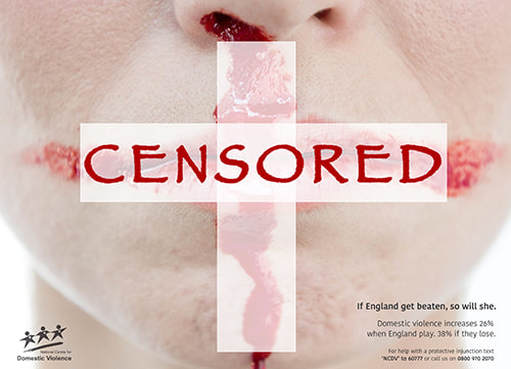

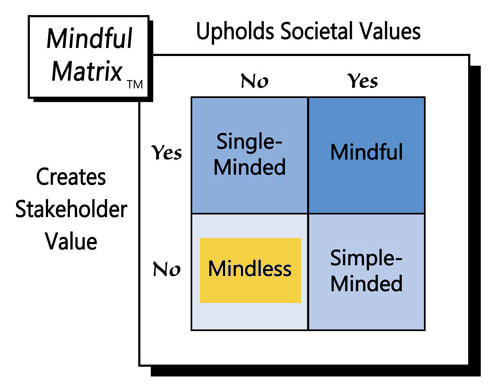

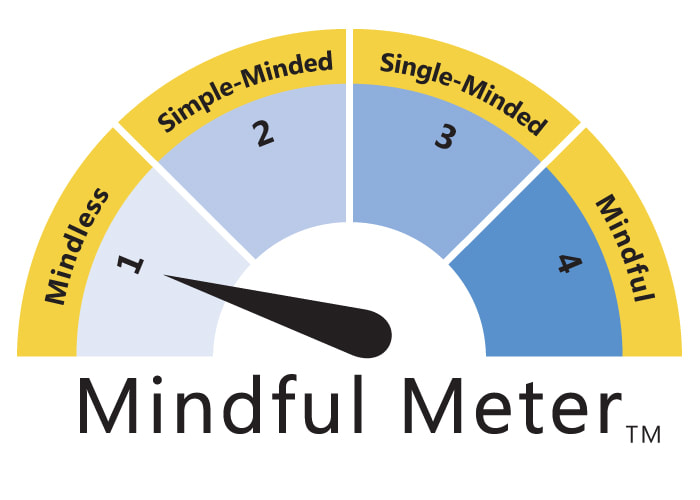

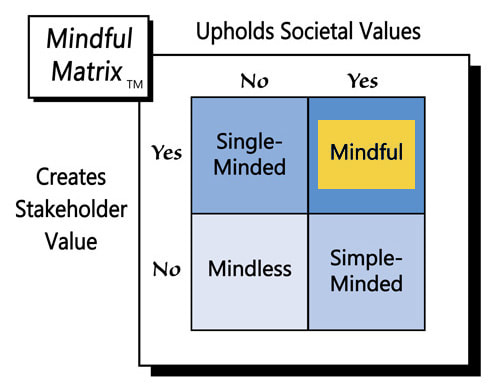

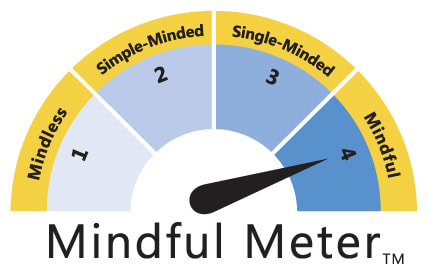

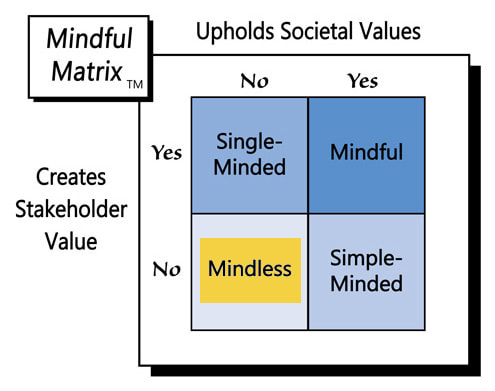

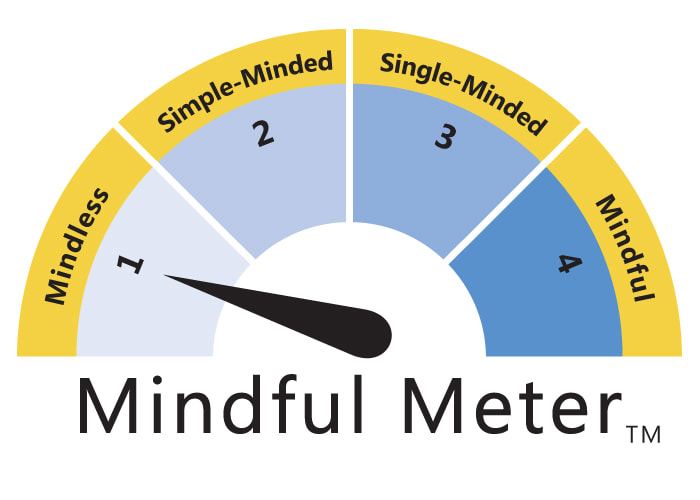

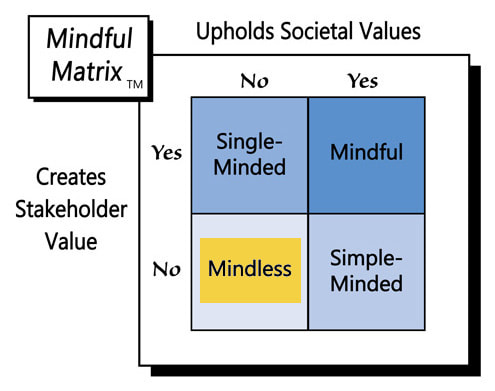

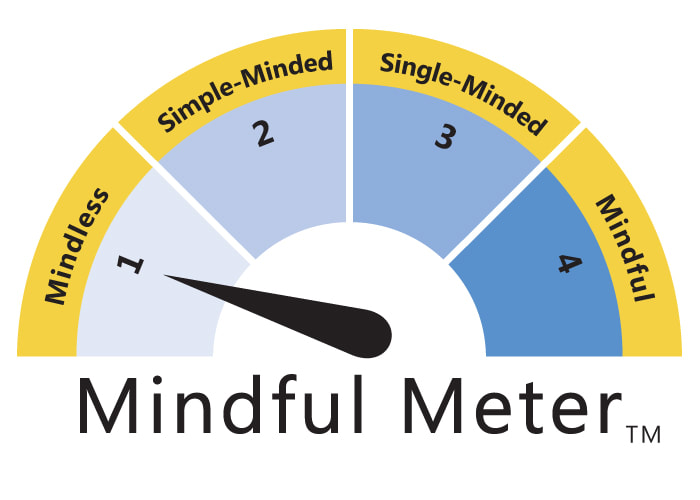

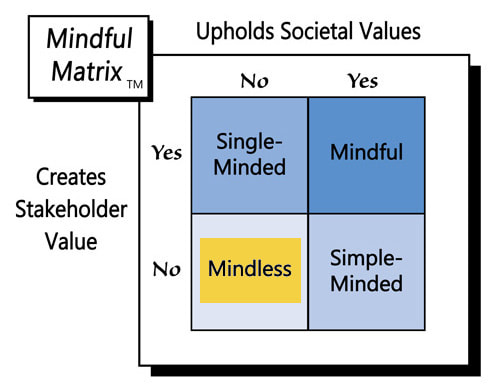

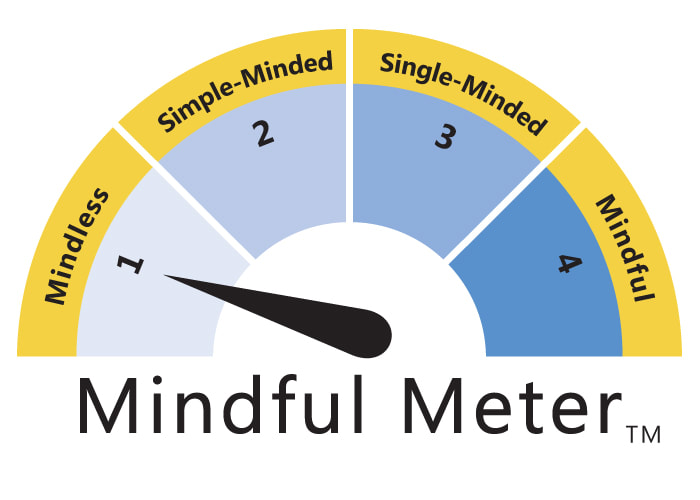

Although I haven’t asked Eric directly, I think we both agree that frequent price changes don’t necessarily mean price discrimination. In fact, dynamic pricing can be an example of “Mindful Marketing.”

Eric Wenger is managing partner at RKL, LLP in Lancaster, PA.

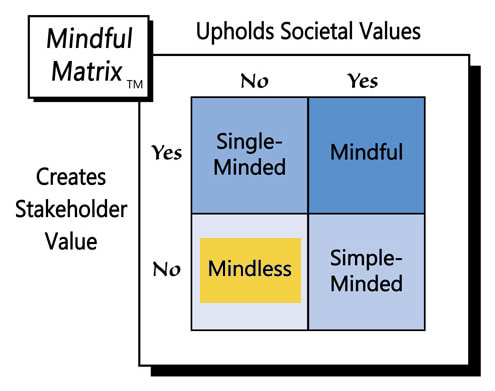

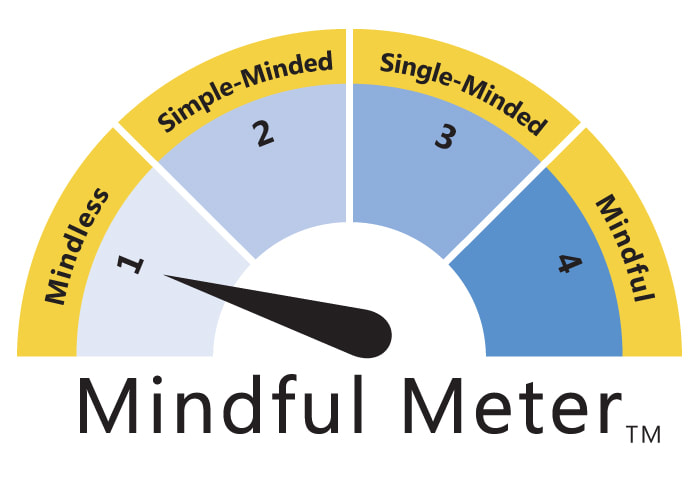

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed