A Colorado man allegedly murdered his pregnant wife and their two daughters.

A week rarely goes by without another disturbing story of domestic violence. In the United States, 20 people are abused by an intimate partner every minute. It’s reasonable to think that such a mass problem requires a mass media solution, but is advertising the answer to decreasing domestic violence?

The United Kingdom’s National Centre for Domestic Violence (NCDV) thought so. The organization that provides “free, fast and effective legal support to survivors of domestic violence and abuse” enlisted the services of world-renown marketing firm J. Walter Thompson (JWT) to produce an anti-abuse ad campaign that ran in Europe during the recent FIFA World Cup.

The “Not-So-Beautiful Game” campaign’s target marketing and timing were insightful: Unbeknown to most of us, there is an unfortunate “correlation between domestic abuse and [soccer].” In England, for instance, domestic violence increases by 26% when its national team plays, and if it loses, incidents rise by 38%.

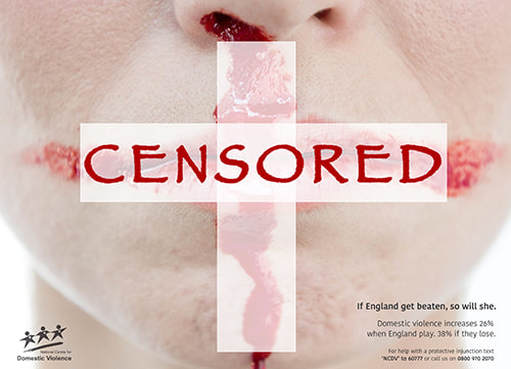

Such alarming statistics encouraged the NCDV and JWT to unleash a jarring counterattack. The ad campaign featured very graphic images of the results of physical abuse, each with a specific soccer team tie-in. For instance, two bandages resembling a Swiss cross barely covered the large gash on a young woman’s bruised right cheek, while the caption read “If Switzerland gets beaten, so will she.”

Another gruesome image was a straight-on shot of the lower third of a young woman’s face, stained and still dripping bright red blood from her nose and lips. The caption read, “If England gets beaten, so will she." Among other media, the ads appeared on Instagram and billboards.

A few years ago, I did a study of shock advertising and found, among other things, that marketers have long used startling words and images to gain attention for everything from clothing to fast food.

Nonprofit organizations seem especially open to employing shock, probably because they find it easier to rationalize it for what are arguably more noble ends, like alleviating hunger and decreasing smoking. It’s not surprising, therefore, that the NCDV campaign was not the first to use shock in the fight against physical abuse. For instance, a few years ago, the Salvation Army of South Africa invoked social media’s famous “black and blue” dress in an ad that showed a woman covered in bruises, with the caption “Why is it so hard to see black and blue?”

Such ads certainly grab attention, but are they effective in accomplishing the creators’ objectives, e.g., decreasing domestic violence? The results I found were mixed: In some instances the target market responded as intended, but in other cases the shock was ineffective or even counterproductive; for instance, it pushed people further from the purpose of the ad because graphic images and language repulsed viewers or overshadowed the ads’ unique selling proposition.

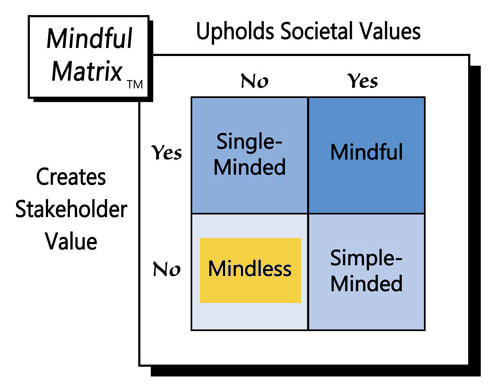

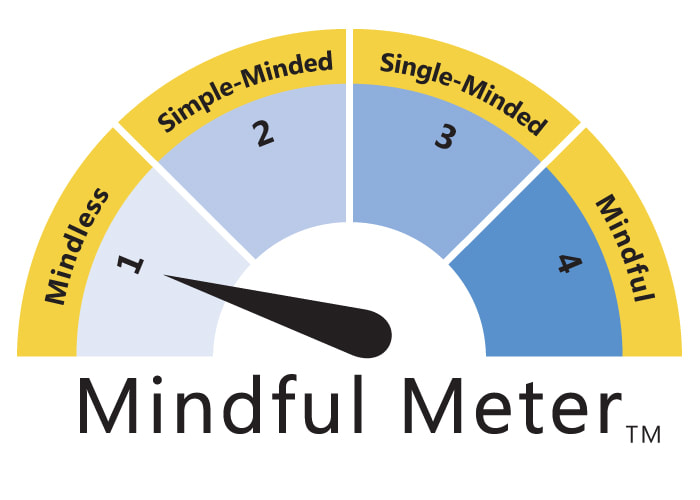

Regular readers of this blog know that effectiveness is only one of the assessments that Mindful Marketers make. The other involves ethics. In terms of shock, even if it works, should advertisers use it to combat domestic violence? Is shocking people the right thing to do?

I don’t know the results of NCDV’s “Not-So-Beautiful Game” campaign, so I’d like to consider the ads’ efficacy and ethicality by posing four specific questions:

1. Were the ads actually a deterrent? A key assumption of the NCDV ads seemed to be that potential abusers would see close-ups of the blood and gore and resolve not to do that to someone. Maybe that motivation works; I honestly don’t know, but it’s easy to imagine that the gruesome visuals could have the opposite effect, i.e., they set off in people predisposed to such violence a visceral reaction similar to sharks sensing blood in the water.

Whenever marketers develop ads, it’s critical that they understand the target market’s underlying reasons for acting. In the case of domestic violence, maybe it would be more effective to appeal to perpetrators’ fear of arrest, like many drunk driving ads do. Or, perhaps these abusers would be motivated by concern over lower self-esteem (“Don’t be a coward”) or by lost love (“She will leave you”).

2. Did the campaign increase desensitization? Studies have found that the more people are exposed to violence, the more desensitized they become to it. The principle of marginal utility supports these findings: The more we have of something, the less satisfaction we gain from getting one more of that thing.

We should wonder what the impact is of increased shock advertising on all of us. Sixty years ago, a huge bloody billboard would have left most people aghast. Today it takes much more to move us. The scariest part is if shock like that of the NCDV’s ads desensitizes the general public to violence, it’s also desensitizing those who are likely to commit violence against others.

3. Do people deserve to be ambushed? Yes, life is full of surprises, but should someone walking down a city street have to come across a large billboard with a blood-soaked face? Or, should a person innocently surfing the web have to see a close-up of a severely bruised and gashed cheek?

For most people, such graphic images are outside the realm of ordinary life. They should have a say in whether they want to see them or not. It doesn’t seem right for advertisers to confront people with such visuals without fair warning or giving them the ability to opt out.

4. Who else saw the ads? The previous question leads naturally to this final point. Advertising is by definition mass communication, which is inherently hard to control, at least when it uses traditional media. A company can choose a billboard based on a location that the target market frequents, but there’s nothing to stop others outside the target market from being exposed to the same message.

That lack of audience selectivity is inefficient, but the bigger problem pertains to those who could be traumatized by shocking images, namely children. Advertisers also should consider the increasingly large number of people who have been victims of domestic violence. They don’t deserve to be vividly reminded of their experience when walking down a street or browsing online.

Advertising that employs shock, like the “Not-So-Beautiful Game” campaign, often rationalizes that ‘the ends justify the means.’ That line of thinking is highly questionable. It’s also unclear whether such advertising actually produces net benefits. The NCDV’s ads may have been well-intended, but they were most likely “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed