You’ve probably noticed the phrase “whole grain” appearing more and more on product packages, ranging from breakfast cereals to bread. What’s your interpretation when you see “whole grain” on the front of a box? It’s reasonable to assume that all of the product’s grain content comes from whole grains, or at least that whole grain is the primary/first ingredient. However, when you turn the box around to read the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) required nutrition and ingredient labeling, there’s often an unsettling surprise.

Many products that promote themselves as being made from “whole grain” actually contain very little whole grain. Instead, their primary ingredient is refined flour, “a pulverized version of what may, at some point, have been a whole grain.” Whole grain contains every part of a grain kernel, “the bran, the germ and the endosperm (the inner most part of the kernel),” whereas the process of refining flour often involves “stripping off the outer layer, where the [more nutritious] fiber is located.”

How is this potentially misleading labeling allowed? Many blame lax directives by the FDA, which last issued “draft guidance on whole grain labeling in 2006.” The FDA, which regulates food labeling, continues to allow food manufacturers to print “whole grain” on the front of their packages without any absolute or relative reference information, i.e., how many grams of whole grain the product contains or how much whole grain there is relative to refined flour.

But, does printing “whole grain” on the front of a food package really deceive consumers? Several significant stakeholder groups believe it does. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has advised the FDA to “require firms to disclose either the percentage of whole grains and refined grains on pack, or the grams of both refined and whole grains per serving.” Similarly, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), a Washington DC-based consumer advocacy group, has “urged the agency to make whole grain labeling clearer to consumers.”

Whole grain labeling becomes even more confusing when it appears on “hearty-looking, and sometimes artificially colored,” food items like multigrain or wheat bread. Such mismatched visuals are especially misleading for the elderly.

But, as consumers, don’t we bear responsibility for what we place into our grocery carts and eventually into our mouths? All we need to do is turn the package around and read the FDA-mandated list of ingredients to see where whole grain ranks into the mix.

Consumers should be expected to act rationally and make logical interpretations about product labeling. However, according to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), it’s unfair to subject people to deceptive messages that a “reasonable consumer” would find misleading. Courts have applied this reasonable consumer standard in ruling against those employing whole grain deception.

The most notable litigation likely has involved one of the best-known snack crackers, Cheez-It, the product of one of the world’s leading food manufacturers--Kellogg’s. In December of 2018, a second circuit appeals court ruled against the packaged-goods icon in a class action lawsuit that claimed deceptive labeling on “Whole Grain” Cheez-Its, a relatively new extension to the company’s flourishing cracker line.

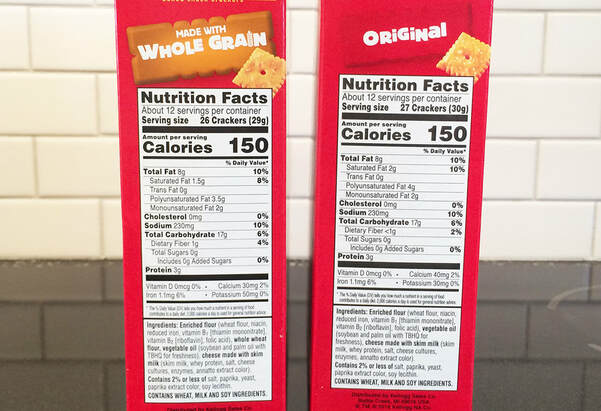

Printed on the front of the box, in large letters, is the phrase “WHOLE GRAIN.” Above those words, in a much smaller font, are the words “MADE WITH.” Meanwhile, a very big (4.5” x 4.5”) and unusually dark Cheez-It serves as a background image. Despite those distinct package design elements, which are very different than those of Original Cheez-Its, when one turns both boxes to the side, the nutrition facts for each list “enriched flour,” not whole grain, as the first ingredient.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that the second circuit appeals court agreed with the consumer plaintiffs, issuing a unanimous decision that said the whole grain cracker’s nutrition facts “contradict, rather than confirm, [Kellogg’s] ‘whole grain’ representations on the front of the box.”

Kellogg’s effort to include more whole grain in its crackers is good in that “scores of studies link the amount of whole grain [people consume] to better health.” So, the 8 grams of whole grain found in a serving of Cheez-Its can help get people closer to the target daily intake of 48 grams of whole grains for adults.

The problem, however, is that when the front of a package promotes “WHOLE GRAIN” in large letters, against a dark background, it’s reasonable for consumers to conclude that the product’s principal ingredient is whole grain. People might even presume that the crackers are somehow healthy, which is a hard argument to make for any snack cracker, including Cheez-Its, which have the following daily values: total fat–10%, saturated fat–8%, sodium–10%, and total carbohydrates–6%.

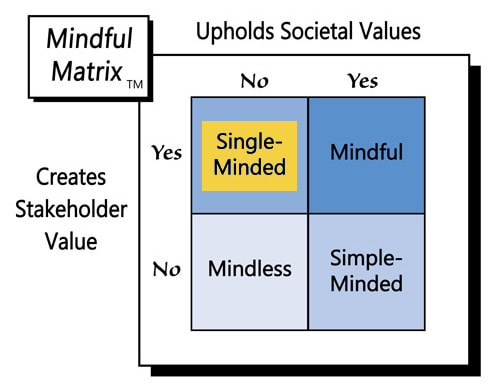

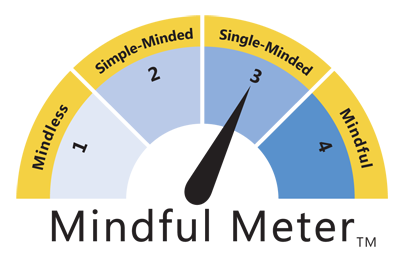

Consumers should read the labels and exercise good judgment for the products they use. However, food marketers also should help people make right choices and not mislead them with mixed messages on product packages. Their continued prevalence on supermarket shelves suggests that Kellogg’s Whole Grain Cheez-Its are a success, but the cracker's first ingredient really is “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed