If you're like most consumers, you've experienced slackfill many times but just didn’t know what it was called. Imagine opening a large bag of potato chips—“poof,” out comes a gust of air. As you look inside you wonder where all the chips have gone, in what looks like a half-eaten bag. Or, you open a bottle of aspirin, and there’s a cotton ball at the top of the pills. The air and the cotton ball are examples of slackfill.

More specifically, slackfill is the difference in volume between the product a manufacturer puts inside a box or bag and the package’s overall capacity. In other words, slackfill fills up the slack.

But why not just make the package the same size as the product and eliminate slackfill? Sometimes extra space is inevitable because product contents settle after containers are closed. Other times the package needs to have air or another cushioning element inside in order to protect breakable goods (e.g., chips) or to make the product easier to display and handle (e.g., a memory card for a camera). Such “functional” uses of slackfill are fine as far as the law is concerned, and they don’t prompt moral concerns for most consumers.

Companies push legal and ethical limits, however, when the slackfill serves no practical purpose but rather makes consumers believe they’re getting more product for their money than they actually are. For instance, some of Procter & Gamble’s and Unilever’s deodorants have prompted lawsuits because the containers of their solid sticks are about twice as large as the product they contain. For example, one 2.6 ounce product came in a container that measured 5.25”H x 2.5”W, while the deodorant stick itself was only 2.5”H x 2.25”W.

Such examples are bothersome, but what’s even more troubling is when a manufacturer decreases the amount of product while continuing to sell it in the same size container for the same price. This was the recent strategy of international spice maker McCormick & Company, which reduced the amount of product in its classic pepper container (2) from 4 oz. to 3 oz.—a 25% decrease. Most consumers would probably never notice such a change while they unwittingly purchased less pepper and got more slackfill.

McCormick chose this stealthy strategy because its pepper costs had climbed, but it didn’t think it could pass on a price increase to consumers. Costs do increase, in which case it’s often unrealistic for organizations to simply absorb them. However, it’s also not acceptable to lead people to believe they’re getting more than they actually are—such deception is one of the main problems with excessive slackfill.

Another problem is the packaging itself. Even casual consumers are increasingly aware that packaging materials cost money and can have a negative environmental impact. Using more packaging than is needed, therefore, represents poor stewardship of valuable resources.

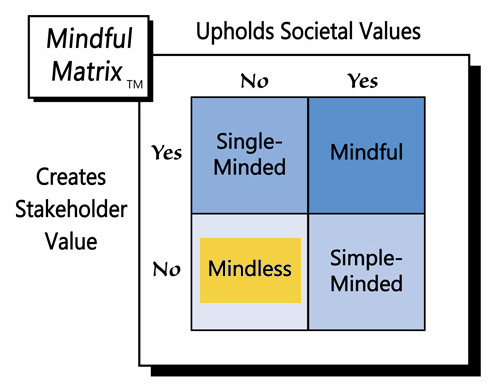

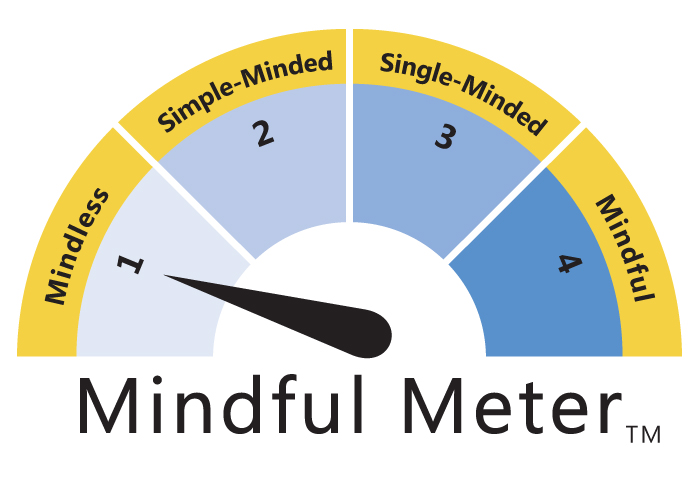

Although companies may get away with a guise in the short-run, people eventually realize when they are being deceived. They also understand the wastefulness of unnecessarily big bags and boxes. For these reasons, the use of excessive slackfill threatens societal values like honesty and environmental stewardship without offering much potential for creating long-term stakeholder value. Needlessly big packaging certainly isn’t better; it’s just “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed