author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

As you may have seen in the 60-second spot from its feel-good campaign, Domino’s bought over $100,000 in gift cards from local restaurants and gave them to its own customers.

It doesn’t take much business background to know that the goal of an enterprise is to build market share for itself, not competitors. Even Vickie Corder, one of the restaurant owners who appeared in Domino’s commercial, was astonished by the action: “I can’t believe one restaurant is buying another restaurant’s gift certificates.”

Why would Domino’s want to support its competitors’ sales by buying their gift cards, and even worse, giving them to its own customers, making them less likely to buy Domino’s pizza? Some of the ad text suggests an altruistic reason: “Domino’s wants to help the people and restaurants in our local communities.”

One might take that explanation at face value. After all, the firm did fork over $100,000. However, for a company with annual revenues of $4.37 billion and operating income of $801 million, $100,000 is immaterial. There’s also some understandable skepticism--Why haven’t we heard before of Domino’s feelings of responsibility for other restaurants?

Instead, some of the chain’s social responsibility has looked more like ‘marketing gimmicks,’ such as its “Paving for Pizza” program, aimed at filling potential pizza-delivery-wrecking potholes, and its “carryout insurance,” guaranteeing free replacements for customers who inadvertently fumbled their pies.

The vast majority of people probably never had a poor pizza experience resulting from either of those issues and never will, so it’s realistic to suggest that in both instances Domino’s was making much ado about nothing, positioning for the free publicity that each unconventional campaign elicited. So, is gifting other restaurant’s gift cards just another attempt to gain exposure through oddity?

The gift card campaign certainly seems like it could be another gimmick; yet, there are some notable differences, namely that COVID has put unprecedented pressure on restaurants, causing many to shutter their doors permanently. In fact, Domino’s commercial mentions that “over 110,000 U.S. restaurants have closed since March 2020.”

That to say, unlike the exaggerated ideas of potholes pummeling delivery vehicles and consumers carelessly dropping carryout orders, the pandemic’s negative impact on restaurants has, unfortunately, been very real.

The ad also mentions a related phenomenon that COVID didn’t cause but did increase: the use of third-party delivery companies. During the height of the pandemic when most restaurants’ sit-down dining was paused, more and more people started getting restaurant food delivered to their homes and offices by providers like Grubhub, Uber Eats, and DoorDash.

Although selling food, whether for dine-in or delivery, seems like a good thing for restaurants, apparently the math doesn’t work well when third-party delivery companies are involved. Irene Li, another restaurant owner interviewed in Domino’s ad, affirms the profit predicament: “[Third-party delivery fees] take a huge chunk of our bottom line; all of that comes out of our pocket and goes to them.”

Others have echoed her concern, including NPR, which reported that apps often charge commissions of 17% or more, in addition to delivery fees. Likewise, the LA Times found that one local restaurant paid $35,000, or roughly a third of its annual rent, in delivery fees, which led the Times to recommend, “The next time you order takeout, call the restaurant [directly].”

Domino’s suggestion that delivery apps wreak havoc on restaurants’ bottom-lines is on-point; however, the pizza chain is also very well-known for doing its own deliveries. Does that mean that Domino’s is selflessly looking out for others? Not exactly.

Apparently, some of the many people who have grown accustomed to the third-party apps for food delivery have also used them to place orders for pizza, doing to Domino’s the same fiscal damage described above. In fact, another Domino’s ad has suggested such delivery difficulties, warning consumers that third party delivery firms charge “surprise fees,” but it will reward certain loyal customers who use its app with “surprise frees,” or, free food.”

Likewise, during an interview on CNBC’s Mad Money, Domino’s President and CEO Ritch Allision suggested that third-party delivery apps have, to some extent, stunted the company’s growth.

All this to say, by buying and giving away other restaurants’ gift cards, Domino’s has brought added attention to an issue that doesn’t just hurt its local restaurant competitors. It also bruises Domino’s own bottom line.

The question, then, becomes, Is it right for Domino’s to help itself while helping others?

Before considering the ethics of this query, it’s worth noting that Domino’s strategy does seem to be effective marketing. The unconventional approach gains attention, and the corporate social responsibility builds goodwill.

What’s more, because delivery is both the focus of the ad and a key component of the company’s value proposition, the promotion is more meaningful and memorable. When people consider Domino’s brand, the company wants them to think of food delivery, which the commercial accomplishes.

So, what about the marketing’s morality? One consideration could be the amount Domino’s spent on the gift cards ($100K+) versus how much it’s paid for the ads. Excluding production expenses, U.S. television broadcasting costs alone, average about $115,000 per 30-second spot, which means the campaign’s promotional budget certainly far exceeded the value of the gift cards.

The extreme imbalance may make some rightly question the company’s motives. Although Domino’s franchisees did assume some risk by giving other restaurant’s gift cards to their own customers, most people who eat out probably patronize multiple restaurants, making it unlikely that Domino’s lost business. In fact, free gift cards may have led some of their recipients to reciprocate by buying more pizza.

All said, it’ hard to paint Domino’s promotion as selfless: The company benefited from the tactics as did the other restaurants and those who scored the free gift cards. So, is such mutual benefit problematic?

Most business exchanges result in win-win outcomes. From the clothes we wear to the computers on which we type, we’re usually very glad we have those products and not the money we paid for them. Meanwhile, the marketers are grateful for our money and don’t want back their products.

Mutually beneficial exchange, in commercial and noncommercial contexts, is a very good thing. Some may argue that such a philosophy shouldn’t extend to corporate social responsibility, but why not?

Several years ago, two colleagues and I conducted research in which we identified three unique types of corporate social responsibility: donation, volunteerism, and operational integration. In the study we affirmed that helping others was very good, but implementing philanthropic acts that simultaneously furthered the economic goals of the organization was even better. The positive response to this article and another like it suggests that many others share the same viewpoint.

The reality outside business isn’t much different. When individuals give of their time, money, etc., benevolence in some form usually comes back to them. The stories found in the Go Giver artfully describe that phenomenon.

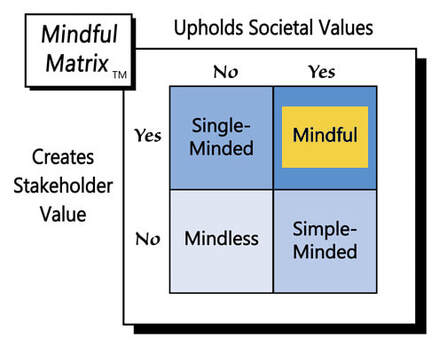

Domino’s did a good thing by buying and giving away other restaurants’ gift cards. Although it wasn’t a major act of corporate social responsibility, it was a meaningful one. The fact that the philanthropy also benefited the pizza chain, doesn’t stop the strategy from being "Mindful Marketing."

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed