Today this scenario may be far-fetched, but within the next few years, or even months, personalized pricing will be within reach of many retailers who then will have a decision to make—whether to charge customers based on what they are willing and/or able to pay.

It’s not surprising that some predict that the airline industry will be the first to implement this approach. Many of us who book flights on-line are befuddled by the variability of ticket prices even for the same seat on the same flight. One day the price is $445 roundtrip; that evening it drops to $385; the next day it’s up to $475.

Airlines already use sophisticated pricing algorithms to maximize seat sales. Currently those formulas consider factors such as number of current bookings and days until takeoff. In the very near future, however, those algorithms might also include variables such as historic seating preferences and where one lives.

Some may be thinking, “But, flying requires much more personal information than is needed from shoppers buying clothing or consumables.” That may be true, however, in the age of Big Data, on-line entities cull more information from our web activities than most of us could ever imagine. Plus, when one takes into account that many of these organizations share their data with others, an even clearer picture of an individual’s purchasing behavior emerges with even greater potential to personalize pricing.

Furthermore, this phenomenon isn’t necessarily limited to eCommerce. Returning to the opening example, even bricks-and-mortar retailers like grocery stores hold the potential for personalized pricing by virtue of their loyalty programs. Of course, most supermarkets will probably never ask their loyalty card holders to report their incomes; however the stores already have detailed records of everything their customers buy, including premium vs. bargain brands and products purchased at full-price vs. on-sale or with coupons. Yes, it will take some advanced mathematically modeling and serious computing power, but the basic infrastructure for charging certain people more already exists.

So, many companies will have the ability to use personalized pricing, but should they? In other words, is it right to charge some consumers higher prices for the same products just because those consumers are supposedly willing or able to pay more?

At this point some may be wondering what the difference is between this pricing approach and, for instance, a restaurant charging one patron $15 for his meal at 5:30 pm, and another $25 for the same meal at 7:00 pm. The key is that the latter pricing difference is not based on consumer attributes but on the time of purchase. Restaurants, hotels, movie theaters, and other service providers are justified in lowering prices during off-peak times in order to even-out demand. Such pricing policies benefit everyone; for instance, those who don’t mind eating during “early-bird” hours get a great deal on their food, while those who prefer to eat later enjoy greater time utility as well as a somewhat less crowed restaurant.

The key is that the aforementioned pricing approach does not favor any specific person. Anyone can conceivable dine earlier or later. In contrast, personalized pricing prevents such individual autonomy and discriminates against consumers based on factors that are at least somewhat outside of their control, as well as beyond their reasonable comprehension. For instance, if I were the second shopper in the opening example, I would have little idea what I could do to receive a better price on my milk.

Is personalized pricing ever justified? One acceptable case may be higher education, which is well-known for charging some individuals more than others. Here’s why it’s likely right for colleges and universities to use personalized pricing:

- Higher education is much more costly than most other things people purchase, which puts it out of reach for many people unless they receive help.

- Education is something that benefits an entire society, not just the individuals who directly receive it.

- Unlike most other cases in which organizations use price discrimination, higher education informs consumers about why and how need is determined and asks them to participate in the process, which is thorough, relatively transparent, and objective (e.g., FASFA form).

- Technically the “sticker price” of college is the same for everyone, but people receive different amounts of aid, much of which is in the form of loans that have to be repaid.

In most other cases, personalized pricing is rather one-sided in terms of stakeholder value: the organizations that use it benefit as do some customers, but many others don’t. Furthermore, even if some firms reap short-term rewards due to consumers’ ignorance of the pricing inequities, it’s unlikely that those returns will last long, as customers will eventually wise-up and take their business elsewhere.

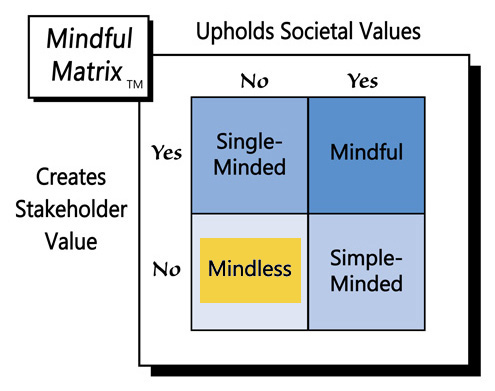

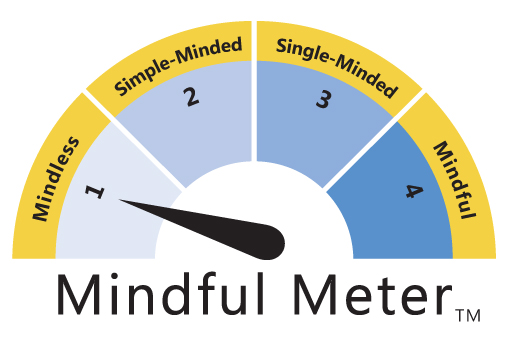

Because of its lack of fairness, its restrictions of purchasing freedom, and its failure to create long-term shared stakeholder value, personalized pricing should be considered “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed