author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Before she was “blindsided” by her abrupt termination, fifty-eight-year-old Lisa LaFlamme was “the face of the most-watched nightly news show on Canadian television.” Her 34-years of industry experience combined with a keen intellect and engaging communication style made her the Canadian equivalent of Katie Couric or Barbara Walters.

However, those talents and experience didn’t stop Bell Media from firing LaFlamme from CTV News. Mirko Bibic, the president and CEO of BCE and Bell Canada, denied that hair color had anything to do with LaFlamme’s release, but LaFlamme’s stunned reaction along with CTV News head Michael Melling’s question of who approved the decision to “let Lisa’s hair go grey,” suggest that hair color was at least part of the reason.

Known for speaking out on body image-related issues, Dove, subsidiary of the Dutch conglomerate Unilever, shared its opinion of the incident: Just a week after LaFlamme’s release, Dove Canada unfurled a #KeepTheGrey social media campaign that included the greying of its iconic logo across social channels “to show support for older women and women with grey hair who may face undue workplace discrimination.”

Fast food chain Wendy’s also took up the mantle, temporarily turning grey the red pigtails of its namesake logo.

It’s nice that brands like Dove and Wendy’s care enough to stand against apparent ageism—an often-overlooked issue, especially in societies that tend to glorify youth. But, what about the companies paying, in some cases very significant sums, to people to represent them and, in some cases, to be the faces of their franchises? Shouldn’t these organizations have a say in how their employees look?

When thinking of organizations that dictate their agents’ appearances, one of the first that comes to mind is Disney. At its theme parks, the company carefully curates a wholesome, family-friendly image that stems in large part from the looks and actions of its staff. Personal branding that’s edgy and provocative may have its place in other firms but not at Disney.

Is it legal for Disney to be so prescriptive with its employees’ looks? Yes, since “no federal law bans employment decisions based on appearance in general.” However, employers must ensure that their looks-related rules don’t intentionally or unintentionally discriminate against people because of their race, religion, sex, national origin, age, disability, or genetic information.

Even then, though, there are legally acceptable exceptions if a case can be made that a specific personal trait is a bona fide occupational qualification (BFOQ). For instance, a film studio can exclude adults from auditioning for children’s roles, and a synagogue can stipulate that rabbi candidates must be Jewish.

As in these examples, for a BFOQ argument to be successful, the required personal characteristic must be essential to job performance. If it is, the discrimination is likely legal.

Of course, just because something is legal doesn’t mean it’s moral, but legislation related to employee looks does do a pretty good job of supporting values of decency, fairness, honesty, respect, and responsibility. For instance, if a certain personal characteristic is critical to job performance, it wouldn’t be fair to those hired or to those who rely on their work (coworkers, customers, shareholders) to disregard the criterion.

To determine what’s fair, honest, etc., organizations should consider three questions:

1. Are the firm’s performance assumptions accurate? A company hiring for a web development position might assume that only those 30 years old or younger have the skills and understanding needed to do the work effectively. It could be, though, that the best candidate is a 60-year-old who has many years of industry experience and has kept themself on the cutting edge of their field.

Similarly, corporations fail when they misinterpret what consumers really want. First, it’s important to emphasize that companies are under no legal or moral mandate to cater to customers’ discriminatory and irrational tastes, like only wanting a Caucasian waiter.

Firms sometimes wrongly assume how customers expect employees to look. Disney recently walked back its longstanding policy of no visible tattoos and now permits employees to display “appropriate” ones — an implied admission that it had fallen out of touch with what its customers viewed as family-friendly physical appearance.

2. Are their double standards? Even as America aspires for equality, there are sometimes conflicting norms for different people-groups, e.g., women vs. men, young vs. old, rich vs. poor, Black people vs. white people.

LaFlamme’s termination is a case-in-point. If she were a man, would it have mattered that her hair was gray? Men may face some stigma for coloring their hair, but when they go grey, they’re often described as looking mature, sophisticated, and wise.

Women with the same hair color enjoy few such positive associations; rather, like LaFlamme, they’re more likely to be the victims of age discrimination: “Because of ‘lookism,’ women face ageism earlier than their male counterparts.”

3. Can the firm help precipitate social change? Given that cultural values and norms are much bigger than any one organization, it’s understandable that companies often believe there’s little they can do to have a social impact, particularly with an issue as far-reaching as people’s appearances.

However, even small businesses can help move the needle on such perceptions with their affirming employment practices (e.g., hiring and retaining older workers), as well as by voicing their disapproval if/when their customers discriminate. Global brands like Dove and Wendy’s can have an even greater impact by virtue of their scale and scope.

In the end, the workplace should be a two-way street:

- Employees should appreciate that they’re agents of the organizations for which they work and as such, need to respect reasonable appearance-related requirements, for their own benefit, as well as those of their coworkers and the organization on whole.

- Organizations should treat their employees with respect and try to truly understand what appearance characteristics are critical to job performance and which are not, while also refusing to cater to customers whose tastes are discriminatory.

There could be a case in which a certain hair color is a BFOQ that a company could legally and morally require. However, that likely wasn’t true in LaFlamme’s situation. She could have reported the news just as effectively with grey hair, and although certain viewers may not have liked her look, many others probably appreciated her authentic appearance and would have welcomed the network’s support of her and other older women.

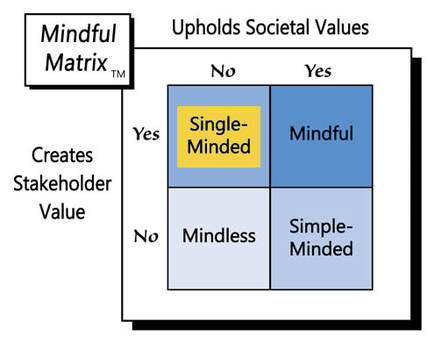

“Queen of England” shouldn’t be the only occupation accepting of grey hair. Looks matter to individuals and organizations, but requiring employees to change theirs for less-than-compelling reasons appears to be “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed