When I first saw The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) article titled, “How Schools can get Children to Eat their Vegetables,” I was skeptical. Generations of very capable moms and dads have tried for decades to push produce with relatively little success. How could school districts suddenly crack the code?

What’s more, I’ve spoken to groups about the simplistic approaches that some marketers take, trying to sell vegetables to young people. For example, several years ago an alliance of carrot farmers led by Bolthouse Farms spent a couple of million dollars on a marketing initiative aimed at positioning baby carrots as junk food.

The strategy relied heavily on promotion, including over-the-top television commercials and “extreme” packaging, but it did nothing to make the product itself more appealing to young people. Although media embraced the campaign and suggested it was successful in two test markets, several years later I still haven’t come across the rebranded carrots in supermarkets or seen anyone eating them.

Marketing aimed specifically at kids also can be a concern. Compared to adults, children have less developed cognitive skills and more limited life experience, which makes them more susceptible to marketing tactics based on deception, coercion, and manipulation.

So, I started reading the WSJ article about kids and vegetables with more than a little disbelief. The article did a good job, however, highlighting and synthesizing research results that in general found that kids were more likely to eat vegetables when schools employed several specific strategies. I’ve summarized those strategies here and categorized each (in parenthesis) using the traditional 4Pmarketing mix:

1. Putting vegetables at the front of the cafeteria: When children saw vegetables first, they were more likely to take them, as primacy effect would predict. (Place)

2. Offering vegetables as snacks: Another study found that timing mattered in as much as kids were likely to take vegetables when they were the only thing offered as snacks outside of regular meals. (Place)

3. Making food easy to eat: Children, especially those with braces, were more likely to eat fruit that was sliced into pieces, rather than try to eat a whole apple. (Product)

4. Creating an appealing presentation: Like adults, kids ‘eat with their eyes,’ which explains why children took more healthy food when it was placed in colorful bowls instead of in gray industrial tubs. (Product)

5. Using enticing promotion: Similarly, researchers at Cornell found that kids ate more fruits and vegetables when those items were promoted via attractive signage and brands (e.g., an Elmo sticker on an apple). (Promotion)

6. Tracking purchases: Two elementary schools in Chicago used digital technology to track the food kids took from the cafeteria line and what they threw away. As in a business environment, this kind of data proved valuable for deciding which menu items to keep and which to cut. (Product)

7. Hiring professional chefs: A key factor in making food taste good is its preparation. So, it’s not surprising that when experts were brought in either to cook the food or design menus, the vegetables tasted better and kids ate more of them. (Product)

8. Educating about vegetables: For many people, food will not make it into their mouth unless they know what it is. That’s why children who were taught about vegetables in their classrooms or on field trips were more likely to try them. (Promotion)

It’s worth noting that out of the eight strategies just described, two involved putting vegetables where and when it was most convenient for kids to eat them (i.e., Place) and four involved enhancing the vegetables themselves or their presentation (i.e., Product). Meanwhile only two of the strategies involved messaging designed to put a good spin on produce (i.e., Promotion). In contrast, promotion was by far the main focus of the ultimately ineffective baby carrots campaign described above.

So there’s empirical evidence to support that more systematic, serious marketing strategies can be effective in getting kids to eat vegetables, but what about the issue of marketing directly to children? Is it fair to use such tactics to target impressionable young people who are not seasoned consumers?

If that question were asked about many other, less edifying goods and services, the answer would be “no, it’s not right.” A society needs to protect people who might easily be taken advantage of by unscrupulous others. However, it’s hard to imagine anything but good coming from increased vegetable consumption, especially when the ones eating them are growing children.

There’s also a greater societal good here. The United States is suffering an obesity epidemic in which one in three adults is obese and another third is overweight. Meanwhile, about one in five school-age children (6-19 years old) is obese, which represents a threefold increase since 1970.

Of course, obesity poses serious health risks for individuals, e.g., high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and certain cancers. Aggregated across the population, such sickness presents a great strain on health systems and comes with considerable financial cost. In 2008, the medical costs of obesity were estimated at about $147 billion, while obesity-related absenteeism was believed to be responsible for lost productivity costing between $3.38 billion and $6.38 billion.

Furthermore, there is the social estrangement the comes with being obese. “Overweight and obese individuals are often targets of bias and stigma, and they are vulnerable to negative attitudes in multiple domains of living including places of employment, educational institutions, medical facilities, the mass media, and interpersonal relationships.” Add to this the unfortunate fact that kids are now experiencing body shaming at younger ages than ever.

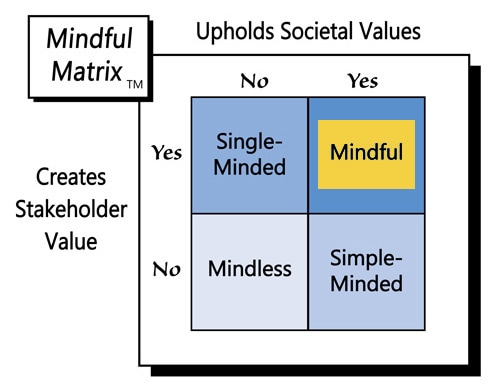

Are vegetables the cure for obesity? No, but eating more of them and less of other food, especially simple carbohydrates, definitely helps. Likewise, marketing that is effective in getting kids to eat more vegetables is good because it is in the best interest of the children and society on-whole. In short, strategies that work to get young people to pick produce represent “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed