author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Beeple’s nonfungible token has been one of several recent high-priced, head-scratching NFT purchases:

- $389,000 for “Death of the Old,” a music video by the musician, singer, and songwriter Grimes

- $580,000 for Nyan Cat, “an animated flying cat with a Pop-Tart body leaving a rainbow trail”

- $3.6 million for “Ultraviolet,” an album by electronic-music artist Justin Blau, aka 3LAU

So, what do people who pay thousands or millions of dollars for such NFTs actually get? They receive proof of ownership of the digital item, which comes in the form of “a unique bit of code that serves as a permanent record of its authenticity and is stored on a blockchain, the distributed ledger system that underlies Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.”

What makes the passion for NFTs puzzling is that people who purchase them gain virtually no exclusive use of their virtual property. For instance, Nyan Cat is ten years old and “has been viewed and shared across the web hundreds of millions of times.” There’s no practical way for the feline’s new owner to stop others from viewing or posting their newly-acquired kitty.

What NFT owners receive amounts to little more than “digital bragging rights.” It’s kind of like holding the title to a car that anyone else can drive. Well, at least the owner can point to the title and say, “It’s mine.”

The possibility that others may be willing to pay even more for certain NFTs can give them value by virtue of their potential resale. There also may come a time when some NFT owners will be able to more readily restrict access to their digital property and monetize their asset.

In that way, perhaps NFTs have become so popular because people notice a troubling trend: Individuals spending their time, energy, and talents to create things of value, only to have ‘anyone with a smartphone’ duplicate and share the work with no consideration of, or compensation for, its creator.

This issue hit home for me recently when I saw this headline in the Chronicle of Higher Education: “Deadman Teaching.” As a college professor, I know how helpless one can feel in front of class when nothing seems to be going right, but the focus of this piece was quite different.

The article described the experience of Aaron Ansuini, a college student who was really enjoying an art history course taught on video by a deeply knowledgeable and enthusiastic “bespectacled, gray-haired professor,” François-Marc Gagnon.

During one of the engaging lectures, Ansuini had a question he wanted to ask his instructor, so he searched for the professor’s name online, thinking it would be faster than locating the syllabus on his laptop. What he found was an obituary--Gagnon had passed away at the age of 83 about two years earlier.

Until then, Ansuini and other students had no reason to think that their professor wasn’t still living. The course syllabus made no mention of his passing, and students had been receiving messages they thought were from Gagnon but must have been from a teaching assistant.

Tom Bartlett the author of the Chronicle article, reached out to one of Gagnon’s children, Yakir Gagnon, a researcher at Lund University, in Sweden. On one hand, the son thought his father would be very happy that his insights were still finding an audience; however, he also wondered about the intellectual property implications and who owned the rights to the work.

As someone who teaches a significant number of classes each week, I can’t help but wonder the same thing: whether ‘digital me’ might keep teaching after my death, but also how copies of my work might be used now without my knowledge or consent. I also can imagine two main objections to such concerns—one related to relevance and the other to responsibility. I’ll try to address both:

1) Relevance: A natural reaction might be, I’m not a teacher, so Gagnon’s case doesn’t apply to me.” However, people in all kinds of occupations write, say, and do instructive things that others will read and watch, if someone digitizes and shares them.

For instance, anyone familiar with YouTube knows its abundance of instructive videos, from cooking rice to repairing cars, which often come in convenient five- or ten-minute clips. Most of the videos are shared with the consent of their creators, but not all, as evidenced in part by many posts that seem prematurely removed. Some pirated videos likely earn money for others without their owners’ knowledge or consent.

2) Responsibility: Even those who understand that unauthorized sharing can potentially affect anyone may still believe that employers own everything their employees do. It’s true that in a principal-agent relationship, the agent (employee) has a fiduciary responsibility to act in the best interest their principal (employer).

In the case of Gagnon, because his university presumably paid him, he (the agent) had a responsibility to do what his principal (the university) required, i.e., to teach art history classes. If for some reason he didn’t want to do that, he shouldn’t have collected a paycheck. However, did paying the professor to teach a specific class during a particular semester give his employer the right to use his digitized teaching to instruct other classes, without giving him or his heirs additional compensation?

In the world before hyper-digitization, such obligations were rather clear-cut: Job performance happened in real-time, largely constrained by a particular place and time. The introduction of early recording and duplicating devices (e.g., video cameras, copy machines) stretched those boundaries.

In the current era of highly-advanced and widely-democratized digital technology, along with broadly-used social media platforms, those boundaries have been blown wide open. Duplication and sharing anyone’s work, including employees’, is incredibly easy and enticingly convenient.

The questions, then, become what employee work is fair to share digitally, where, and for how long. Some may suggest that employers hold complete sharing rights during and even after the agent-principal relationship has ended. Perhaps such broad employer ownership could be justified if agreed to with informed consent, but even then, the agreement would only be fair with appropriate compensation.

What is appropriate pay? It might be a percentage of the present value of projected future earnings from the digitized work. Or, it could be royalties, or residual income, that accrues whenever the work is shared. The latter suggestion may seem unreasonable, but there is strong precedent in the form of television actors who are often compensated with royalties for each episode that airs in syndication, or songwriters who earn money every time their music is sold or played.

Although some undoubtedly do this, it would be unfair to pay a musician to play a piece once, record the performance without her knowledge, and make money by selling her art without her consent. But again, even if there is informed consent, people deserved to be fairly compensated for their digitized work when it’s shared and continues to bring in dollars.

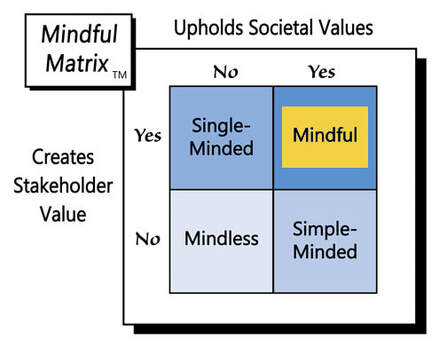

In a sense, everyone is an artist, creating content that benefits others now and perhaps into the future, if digitized and shared. Maybe that future will include more robust ownership standards based on blockchain systems for sharing. The current fervor for nonfungible tokens may be unfounded, but NFTs might be writing a script for more “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed