The market for genetic testing exploded in 2017, and it keeps growing. Some predict sales of over $22 billion by 2024, driven by top competitors like 23andMe, AncestryDNA, Family Tree DNA, MyHeritage DNA, and Living DNA. Over 12 million people already have had their DNA tested.

What exactly does DNA testing do? It depends on the test, of which there are three main types:

- Autosomal: Both men and women can take this test, which estimates an individual’s ethnicity and cousin matches on both maternal and fraternal sides over about 5 to 6 generations.

- YDNA: Only men can take this test, which tracks Y chromosomes passed from fathers to sons over many generations.

- mtDNA: Both genders can take this test, which examines genetic markers only along mothers’ material lines, and also provides the user’s haplogroup.

Autosomal tests appear to be the most popular of the three, as they’re the ones we most often see advertised, with consumer-friendly price points between $49 and $99. These tests are good at helping users fill out their family trees. AncestryDNA, for instance, claims it can search for relatives of the test taker among its 10 million-person database and promises to “confirm ethnicity percentages and close relationships with a high level of accuracy.”

AncestryDNA is also able to help users see migratory patterns through its Migrations tool. This feature identifies a subject’s ancestors “associated with one of more than 300 genetically based communities in the years between 1750 and 1850” to determine migration paths in the U.S. and overseas.

Some autosomal tests have pushed the information envelope even further by providing health reports. For example, 23andMe’s Health+Ancestry test informs users of whether they appear to be a carrier for more than 40 genetic conditions, it provides insights on genetic-related wellness indicators such as lactose intolerance, and it identifies genetic risks for things such as Parkinson’s, late-onset Alzheimer’s and Celiac disease.

People who purchase DNA tests certainly receive unique information that’s at a minimum entertaining, if not educational and possibly helpful in addressing potential health problems. Considering how much many consumers spend on a dinner out, a concert, or a ballgame, a genetic test seems like a pretty good deal. However, there are potential costs for DNA testing beyond the initial cash outlay.

Perhaps the biggest nonfinancial cost is the risk of lost privacy. Genetic testing companies seem to have safeguarded customer information so far—there’s yet to be a major data breach—but the potential risk from carelessness or maleficence is considerable according to New York Senator Chuck Schumer (D), who contends: “Now, this is sensitive information, and what those companies can do with all that data, our sensitive and deepest information, your genetics, is not clear and in some cases not fair and not right.”

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) appears to share Schumer’s apprehension as evidenced by its investigation of the data policies of 23andMe and Ancestry and by the following statement: “A major concern for consumers should be who else could have access to information about your heritage and your health.”

What exactly are the risks of misappropriated DNA data? One possibility is that some organizations may conduct controversial research such as looking for connections between race and intelligence. Although such risks for entire people groups are probably few, there are many risks that could impact specific individuals.

This past spring, California detectives revealed that they tapped a public genealogy database to break the longstanding case of the Golden State Killer, identifying suspect Joseph James DeAngelo. Although few may object to the use of public DNA data to catch a serial killer, the possibility of government accessing such information for other reasons gives many people pause.

For instance, what if police were to use genetic information to predict those likely to commit crime, along the lines of the 2002 sci-fi thriller Minority Report? Such use is farfetched, but it’s not unreasonable to imagine public officials employing DNA data to identify government protestors or others who reject their policies.

Perhaps even more realistic is the possibility of businesses leveraging DNA data for profitability purposes. Life insurance companies, for example, might analyze genetic information in order to determine if someone is a good policy risk. Likewise, any company could take a similar tack in deciding whether to hire a prospective employee.

But, do these risks really exist if companies safeguard users’ data and only share it in anonymous form? First, an endless series of high-profile data breaches suggests that hackers are capable of penetrating the defenses of the largest and seemingly most secure organizations. Second, when people submit genetic tests, they often provide information that allows for individual identification, e.g., age, gender, address. Third, police and government might pressure companies to share their DNA data.

Why, then, do people continue in droves to mail their DNA to genetic testing companies and why do most of those users agree to share their DNA with the firms’ research partners. Maybe consumers don’t have a good understanding of the risks. More likely, they recognize that the potential risks are very remote, while the benefits they receive are very real and meaningful, for instance:

- Knowing one’s family history: It can be deeply satisfying to learn things about one’s ancestors and the places from which they came. That kind of information often helps us better understand ourselves.

- Realizing potential health risks: Of course, it’s important not to obsess about such risks; however, such knowledge can be a very helpful lens through which to view our bodies and perhaps take preventative steps

- Reuniting with lost family members: This benefit doesn't apply to most genetic test takers, but some have discovered lost siblings and other relatives through the process.

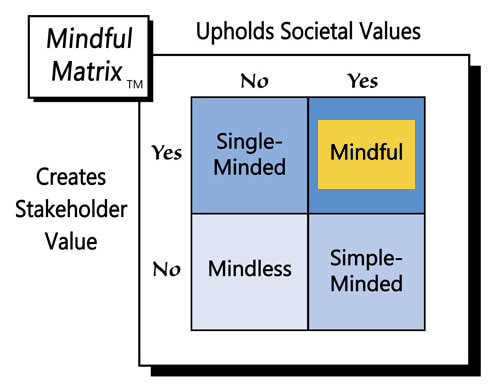

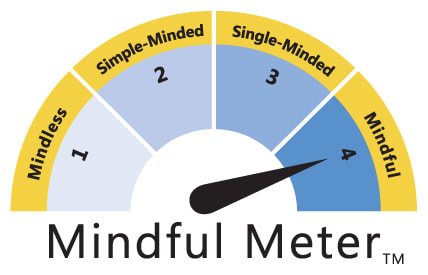

Life is full of risks—much of what we do to survive and thrive involves deciding which risks are worth taking. Perhaps the risks of DNA testing will increase over the coming years. Right now, though, the risks seem remote while the benefits are real, which makes it easy to understand why so many people take genetic tests. It also makes it reasonable to suggest that the firms offering the tests are responsible for “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed