author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

No athlete, or anyone, likes to be picked to lose. However, life is full of potential successes and failures that people need to predict. For some, those predictions offer significant money-making opportunities. But, is it right to earn a living betting against others?

As for many, the practice of short selling stocks burst onto my radar screen when GameStop’s shares took their rollercoaster ride several weeks ago. With more than a casual interest, I followed the ensuing events, including Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev’s testimony before Congress. Along the way, I gained a better grasp of what short selling is, but ever since, I’ve been wondering whether anyone should be doing it.

In case you’ve forgotten how short selling works: Investor A borrows from a broker 100 shares of XYZ at $100 per share and sells the stock to Investor B at the same prevailing market price, or $10,000 total. Over the next week, XYZ’s stock price drops to $75. Investor A then buys 100 shares of XYZ for $7,500 and returns them to the broker, pocketing $2,500 in the process, less any interest and commissions the broker has charged.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has made short selling legal. However, even with this regulatory approval, the practice should raise at least two red flags, or moral concerns, that lead one to ask: Is short selling ethical?

Before addressing the two concerns, I imagine some may be wondering what short selling has to do with marketing—the other half of this blog’s two-pronged focus. Short selling is marketing in that many stockbrokers, including very well-known ones like Interactive Brokers, TD Ameritrade, and Charles Schwab, market short selling among their investment services, or ‘products.’

For instance, Interactive Brokers’ website contains a Shortable Instruments (SLB) Search tool: “a fully electronic, self-service utility that lets clients search for availability of shortable securities from within [the firm’s] Client Portal account management platform.” The relative ease with which an investor can sell short makes its moral implications all-the-more important.

First Red Flag

‘Selling something that one doesn’t own’ was the short selling issue that initially gave me pause. Peddling another’s property certainly appears problematic, until one begins to consider the many ways in which such leveraged transactions regularly occur: from apartment subleases, to bank loans, to consignment clothing. Individuals and organizations often sell others’ property on consignment.

Of course, just because consignment occurs doesn’t mean it should. Still, the fact that all parties involved 1) willingly participate and 2) typically benefit are good signs that most of these activities are above-board.

Second Red Flag

The prior examples differ from short selling, however, in the second of the two ways: While the participants in apartment subleasing, etc., generally rise and fall together financially, a short seller’s success comes courtesy of two others’ failures, namely 1) those of the company whose stock the short seller has borrowed and 2) the person who buys the stock from the short seller. The short seller makes money when the other two parties lose theirs.

In contrast, consider again the clothing consignment example: If I take an unwanted suit to a consignment shop, both the consignor and I will want a high price when the suit is sold. Conceivably, the suit’s maker also would like its aftermarket products purchased for higher prices because such resale value reflects favorably on the brand, not unlike the way higher vehicle resale prices benefit automobile manufacturers’ brands.

On the other hand, the suit’s buyer would like to pay a lower price, but even he really doesn’t want the price to be too low, since perceptions of the brand are tied, at least in part, to the price that he and others are willing to pay for the suit. Most importantly, each time he wears the suit, he extracts value from it.

The suit is this example is analogous to the stock. Whereas everyone ‘invested’ in the suit seems to want it to retain its value, investors who short stocks clearly want the value of those securities to decline. Short sellers are betting against the very companies whose financial instruments they have borrowed and sold, as well as the individuals on the receiving end of those stocks.

The zero-sum game, or winner-loser outcome, that underlies short selling is certainly atypical of most economic exchanges, but it’s not without precedent. Casinos win when their customers lose, as do many “rent-to-owe” retailers like Rent-A-Center and Aaron's. Any kind of predatory lender falls under the same unseemly umbrella, including certain credit card companies that don’t make money unless people fail to pay off their account balances and become locked into an endless cycle of exorbitant monthly interest payments.

However, many argue that short selling does not do anything nearly so destructive. In fact, some contend that the practice produces several important economic benefits, the primary one being liquidity, “the efficiency or ease with which an asset or security can be converted into ready cash . . . . ”

In my research, I found market liquidity to be the factor cited first and most often in the defense of short selling. However, at least one financial markets expert suggests that advantage is exaggerated.

Dwayne Safer is a chartered financial analyst (CFA) whose career has included significant roles in investment banking, corporate finance, and strategy. For the last five years, he’s been a professor of finance and my colleague at Messiah University. When asked about short selling and market liquidity, he offers a contrarian analysis: “the liquidity offered by short selling for most stocks is negligible.”

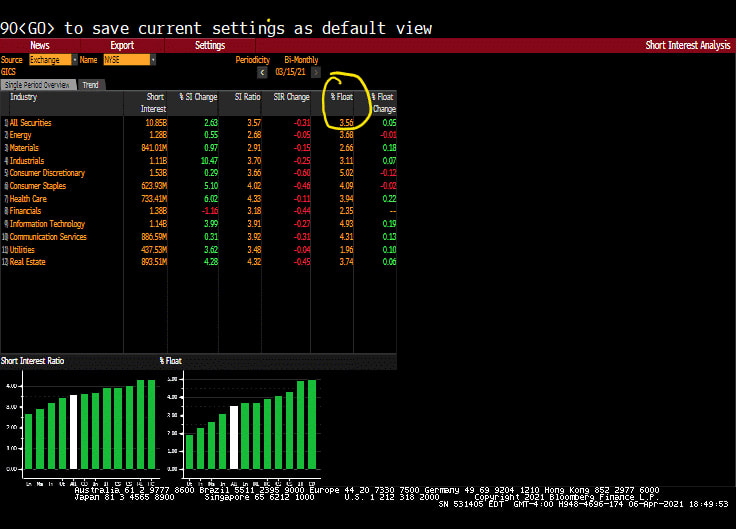

Safer supports his suggestion by sharing a Bloomberg Terminal screenshot (below) that shows that shares sold short represent only about 3.5% of trading volume on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). He also cites an example from the financial crisis in late 2008, when the SEC temporarily banned the short selling of financial stocks “without any noticeable degradation of liquidity in those stocks.”

Safer recognizes that there may be some “modest liquidity benefit” for certain heavily shorted stocks; for instance, at the time we spoke, 21% of Dick’s Sporting Goods’ shares available for trading were short. Still, he affirms: “If shorting wasn’t permissible, liquidity would be brought into the market by the broker-dealers and market makers who would stand ready to buy and sell shares of a given company to generate trading revenue.”

So, does the elimination of liquidity as a main benefit of short selling leave no morally tenable ground on which short sellers can stand? Not necessarily.

Safer continues by saying that although he doesn’t agree with conventional wisdom that short selling adds significant market liquidity, he does believe short selling offers other meaningful market benefits:

- It provides the ability to hedge/protect a portfolio from downward movement in stock prices, mitigating portfolio volatility.

- The in-depth research short sellers often conduct can expose fraudulent companies. For example, short selling hedge funds warned about the frauds at Enron, Tyco, Fannie Mae and more recently Luckin Coffee and Nikola.

- Shorting helps prevent overinflated securities prices that waste valuable capital and harm investors, as occurred in the dot-com bust in 2001. Former SEC chairman Christopher Cox once stated, "We need the shorts in the market for balance so we don't have bubbles.”

Before beginning to write this piece, I was unaware of these important benefits of short selling. Still, how do we reconcile such consequences with the moral principle of respect, or as my second red flag/concern described: not betting against another person.

That moral principle certainly has merit, but my earlier discussion probably represented too narrow a view of short selling. Safer’s observations have helped me see that there are other factors to consider and parties to take into account, e.g., other investors, firms’ customers and employees, and the economy as a whole.

I’m also helped by remembering a story I heard just a few days ago: A guest speaker in our capstone marketing course mentioned that a former client of his used to tell him, “I pray for my competitors.” This very successful business owner was not being sarcastic—he truly wanted his competitors to succeed both because he genuinely cared about them and because he understood that “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

Returning to the basketball metaphor that began this piece, no serious athlete wants to be on the winning side of a forfeit. Basketball players need competitors, who also happen to have fans rooting for them.

However, choosing loyalties isn’t unique to picking stocks or selecting sports teams. Each day we make dozens of similar decisions when choosing what clothes to buy and where to order takeout. Each selection of a company is essentially a vote against another; however, other people are voting for the competitors. In fact, the next time one of those ‘other’ votes may be ours.

Meanwhile, a ‘no vote’ conveys valuable information to all who are willing to listen and learn from it. When companies assimilate such negative feedback, they make themselves better, their industries stronger, and stock markets more stable.

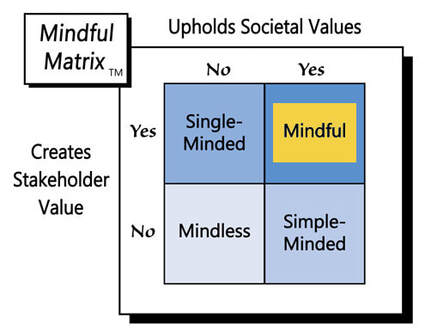

It’s very unlikely that a mother bets against her own daughter or son for anything, but other ‘no votes’ are not necessarily bad. Short selling a company’s stock can be a good or bad bet for the investor. It also can be “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed