Price gouging is "the practice of raising prices on certain types of goods and services to an unfair level, especially during a state of emergency." Although it’s not uncommon for companies to increase prices on goods and services to levels that consumers think are too high, price gouging is different.

Consumers are price gouged when the item in question is something they must have (e.g., food, water), but the product’s supply is severely restricted, often to a single seller, so consumers have no choice but to pay the exorbitant price. In contrast, although the new iPhone X starts at a staggering $999, Apple is not guilty of price gouging because it’s possible to survive without the newest iPhone.

In the case of Hurricane Irma, certain sellers reportedly gouged consumers for water, ice, food, and fuel. One Orlando Shell station supposedly sold regular grade gas for $5.99/gallon and premium for $6.99. Even Disney got into the act: A Twitter user posted pictures from Disney’s Art of Animation Resort, which offered small bottles of water for $2 and juice boxes for $2.69 each. A Disney spokesperson later said that the situation was an isolated incident that had been rectified.

To document such abuse, Florida’s attorney general Pam Bondi set up a hotline that received over 8,000 calls about price gouging, which violates Florida law and is subject to “civil penalties of $1,000 for each violation, and up to $25,000 for several violations within a 24-hour period.” Beyond the legal penalties, Bondi promised violators personal retribution: “I will be saying your name all over national television and telling people not to go to your business ever again if you’re stealing from Floridians and taking advantage of Floridians in a time of need.”

Despite the fact that certain states have made price gouging illegal and most people consider it immoral, some claim that capping prices actually makes situations, like those surrounding hurricanes, worse. Writing for Forbes, Adam Millsap argues that pricing gouging laws are what empty store shelves, not natural disasters. The best thing, Millsap contends, is to let supply and demand determine prices like they normally do.

Similarly, in a New York Times article, Andrew Ross Sorkin states that “several respected economists from the Milton Friedman school of free-market theory” support the argument against price gouging laws because artificially low prices “remove the incentive for consumers to conserve essential supplies,” and they discourage sellers from increasing stock.

So, maybe Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” is the best way to determine supply when natural disasters strike. That belief aligns well with an increasingly popular pricing strategy, dynamic pricing, in which firms like airlines use algorithms to quickly increase prices to whatever level the market will bear. Unfortunately, such approaches also tend to have some very undesirable side effects.

For one thing, higher prices naturally favor the wealthy. That advantage is understandable under normal circumstances: People with more money should be able to buy higher-priced items. In the case of natural disasters, however, it doesn’t seem right to price anyone out of the market for food, water, or other basic survival needs.

Also, there’s no reason retailers can’t impose limits on how much or how many of an item customers can buy. Stores successfully ration items all the time. For instance, a grocery store runs a sale on granola and dictates: “Limit, two boxes per customer.” Likewise, arguments against price gouging laws don’t give people much credit. When asked to conserve, most individuals will limit their consumption for the sake of others.

In addition, the notion that businesses should maximize profits at their customers’ expense is both antiquated and short-sighted. Sure, people may have no choice but to pay ridiculously high prices when they’re put between a rock and a hard place, but they won’t soon forget what it felt like to be treated as a means to an end. Firms that price gouge run a great risk of alienating consumers and ruining their reputations.

On the other hand, companies that show restraint and price “to create shared value,” generate considerable goodwill, especially in the face of a natural disaster. A few firms that bolstered their brands by taking this more enlightened and socially responsible approach when Irma struck were JetBlue, Airbnb, AT&T Wireless, and Martin’s Famous Pastry Shoppe.

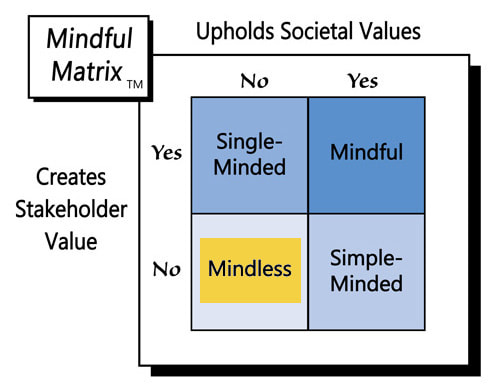

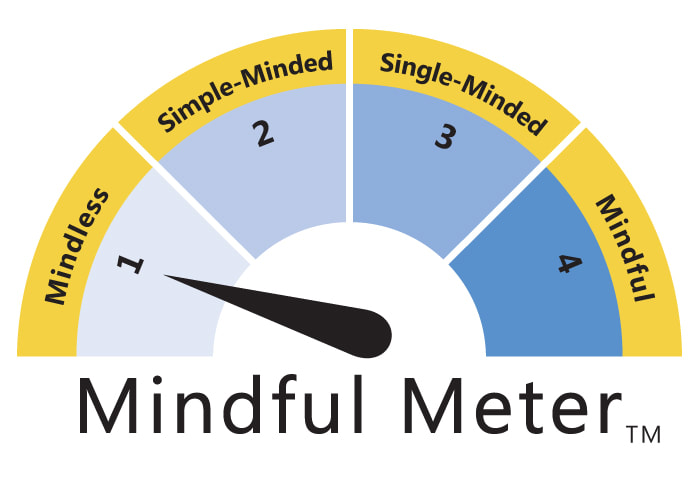

It’s hard for most people to know how they will react in the face of life-threatening natural disasters like hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Businesses, however, should know not to take advantage of people in such vulnerable states. Companies that do are guilty of various offenses, and one of them is “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed