According to Nathan’s Famous, people have been gathering at its first hotdog stand on Coney Island, NY every July 4th since 1916, to see who could devour the most dogs. The first recorded contest came in 1972. Since that time, Nathan’s has built the event into a media spectacle that attracts contestants from around the world, draws over 40,000 spectators to Coney Island, and engages nearly two million viewers on the ESPN broadcast.

Yes, ESPN televised the event live, and SB Nation provided a thorough recap of the action. Does that mean that eating qualifies as athletics? If so, the United States, which ranks as the 12th most obese country in the world, might also be one of the most athletic!

Although we shouldn’t expect eating to become an Olympic event anytime soon, it’s helpful to understand exactly what competitive eating is and why it’s so popular:

“Competitive eating, or speed eating, is an activity in which participants compete against each other to consume large quantities of food in a short time period. Contests are typically eight to ten minutes long, although some competitions can last up to thirty minutes, with the person consuming the most food being declared the winner. Competitive eating is most popular in the United States, Canada, and Japan, where organized professional eating contests often offer prizes, including cash.”

Beyond individual participants, there are actual organizations whose mission is consumption as sport, most notably Major League Eating (MLE), “the world body that oversees all professional eating contests.” Its logo features a hand holding a fork. MLE’s website lists dozens of official eating contests ranging from oysters to ice cream sandwiches, with prize purses between $1,750 and $40,000. Chestnut has won many of these events, including Nathan’s contest 10 times, which gives new meaning to the saying “eat to live.”

Surprisingly, Chestnut, Miki Sudo, who ate 41 hotdogs to take the women’s title, and most other competitive eaters are not big people; they’re average-size, and some are even very fit. So, how do they eat so much? Here’ the basic strategy:

“Many competitive eaters, like those competing in the Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest, practice stretching out their stomachs for the main event by drinking gallons of milk or water very quickly, or by downing lots of filling, fibrous foods like watermelon and oatmeal in a matter of minutes.”

Nathan’s website goes on to explain the exercise and eating regimens of many of its contestants:

“Despite consuming mass quantities of high-calorie foods during competition season, most professional competitive eaters are very fit. Many contestants weight train and exercise vigorously to build muscle and increase their metabolism. Most also eat healthy, low-calorie diets after competitions. Why? Because their stomachs are so stretched out, they can no longer tell when they’re full!”

So, maybe competitive eaters are athletes who deserve more recognition for their accomplishments. Not so fast. It’s also important to consider the ‘damage’ they do to themselves and potentially others through their day-of-event activities.

For instance, Chris Weller of Business Insider wrote an article titled “The terrifying totals of calories, fat, and sodium consumed at Nathan's Famous Hot Dog Eating Contest,” in which he presented the nutritional numbers for the 72 Nathan’s Famous skinless beef franks (4 kg) and 72 Ball Park hot dog buns (3 kg) that Chestnut quickly consumed this past July 4. Here are some of those statistics, which include the metric weights and their respective percentages of daily nutritional values:

- Fat: 1 kg, 1606%

- Saturated Fat: 360 g, 1800%

- Cholesterol: 2 g, 667%

- Sodium: 46 g, 1917%

To help put these numbers into perspective, that’s about 16 days’ worth of fat, 18 days’ worth of saturated fat, and over 19 days’ worth of sodium, all packed into a ten-minute timeframe. Of course, Chestnut and his colleagues aren’t downing those kinds of calories (19,433), every day, but if competitive eating is their job, they’re engaging in similar indulgence more than a few times a year. Even if someone exercises regularly and maintains a trim physique, it’s hard to imagine that kind of extreme consumption doesn’t take its toll over time.

Such overeating reminds me of a now-defunct television show I watched several times, not without misgivings: the Travel Channel’s “Man vs. Food.” In each episode, host Adam Richman visited a different city where he interacted with locals at a couple of their favorite restaurants and eventually took on a mammoth eating challenge, like a 5 lb. sandwich.

After four seasons of such extreme consumption, Richman retired from the popular series without offering a specific reason; although, some suggested there were “concerns over ensuring Adam Richman's health if the show had continued in its previous format.” Richman has since lost about 70 lbs.

Some may argue personal choice: “If people want to tackle food challenges as TV show hosts or as competitive eaters, it’s their prerogative. They’re only affecting themselves.” Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

While an individual’s gluttony does primarily impact him/her, it also affects others by virtue of the fact that we’re social beings who often learn from and emulate the behavior of others. That influence is greatly magnified when mass media share the actions, and it’s even worse when the destructive behavior is presented in a positive light.

The bottom-line is competitive eating glamorizes gluttony. Chestnut and other eating contest winners receive prize money and they’re lauded as champions. There’s nothing praiseworthy, however, about stuffing oneself with 72 hotdogs in ten minutes.

True, few rational people will attempt to consume the quantities of food that competitive eaters do, but they’re still teaching wrong attitudes toward food, e.g., that eating is sport and that it’s okay to continue consuming even after you’re full. Those are likely the kinds of beliefs that have helped place America 12th on the list of the world’s most obese nations.

Competitive eating comes into even poorer taste when one considers the hundreds of millions of people around the world who don’t have enough to eat. “The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that about 795 million people of the 7.3 billion people in the world, or one in nine, were suffering from chronic undernourishment in 2014-2016.”

According to Poverty.com, it’s estimated that “a person dies of hunger or hunger-related causes every ten seconds.” That means about 60 people passed away during the time it took the Nathan’s competitors to each down several dozen calorie-heavy hotdogs.

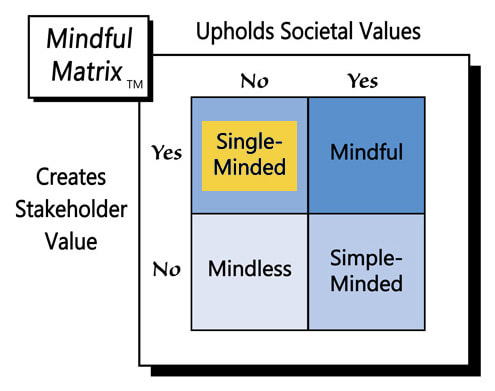

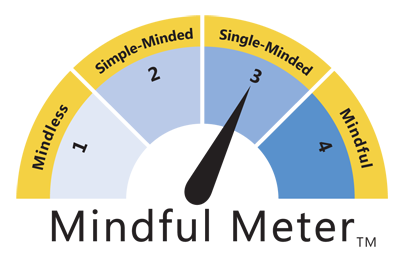

Competition is generally a good thing that brings out the best in people. Competitive eating, however, showcases an unseemly side of humanity—one that’s harmful to its participants, as well as to hosts of others. Given the great attention it receives each year, Nathan’s Famous Hotdog Eating Contest appears to be effective promotion, but the bad behavior it encourages makes the competition an example of “Single Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed