author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

The New York Times recently described a case in which, after some cosmetic medical treatments, a reader’s dermatologist asked her for a tip. If some physicians are soliciting gratuities, is it only time until other professionals start doing the same? Should professors like me put out tip jars?

We’ve all added a tip to a restaurant check, handed cash to a bellhop, or Venmoed a little extra money to another service provider. While physical tip jars have become increasingly common on retail store counters, digital technology has made it extremely easy for anyone accepting electronic forms of payment, in person or from afar, to casually ask for extra cash.

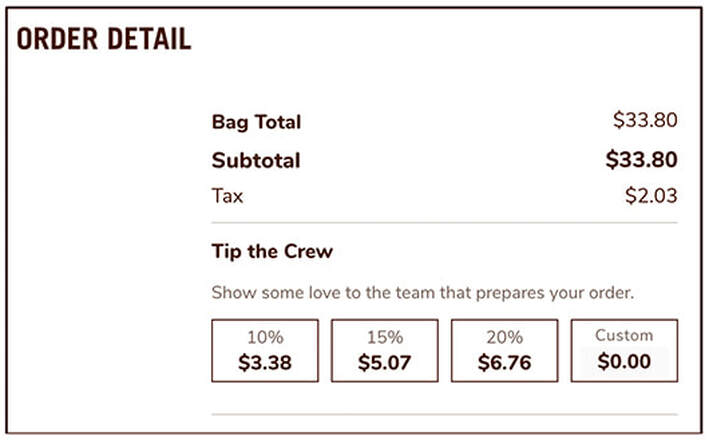

For instance, I recently placed an online order to pick up dinner from Chipotle. When I went to check out, just below the order total a prompt appeared: “Tip the Crew – Show some love to the team that prepares your order.” As I’ve grown accustomed to doing, I clicked one of the tip amounts but not without thinking, “Do I really need to?”

A decade or two ago, one would usually only tip in a sit-down restaurant where a waiter or waitress took your order, brought your drinks and food, stopped by your table to see if you needed anything else, delivered the check, and processed your payment. As the word “gratuity” suggests, your tip was a way of saying thanks for their multipronged service, and the amount you gave was a way of expressing how good you thought the service was.

In the case of Chipotle, no one did any of the aforementioned things for me, so it seemed reasonable to wonder, “Who exactly am I tipping and why?” The easy answers to these questions are the restaurant staff that prepared the food and placed it in the carryout containers because they work hard for low wages, but even if those inputs and circumstances warrant tipping, how similar are they to those of other occupations that are also now panning for tips, including at least one dermatologist?

The complexities and potential inequities in tipping are further illustrated in examples like this one in Sanibel, FL. A couple of years ago, Island Cow, a popular restaurant on the island, was ordered to pay $222,000 to 48 employees because it created an illegal tip pool that “required tipped employees to share earnings with non-tipped workers, including dishwashing assistants and kitchen expeditors.”

This incident and others like it prompt a variety of questions and concerns including:

- Do tips always make it to their intended parties?

- Do owners sometimes pocket tips for themselves?

- Do workers who don’t deal directly with customers deserve to be tipped?

- Why don’t companies just pay their employees more so they don’t need to receive tips?

The last question may simply seem hypothetical, but a recent visit to Europe reminded me how services can be delivered effectively with just base pay and little or no tipping. A few times, when dining out in France, I received my check, which had no place to add gratuity. When I asked how I could leave a tip, the waiter/waitress replied that tipping wasn’t necessary.

Of course, that norm is not indicative of every restaurant in France, and it’s certainly not true across all Europe, where the likelihood of tipping varies widely from rather unlikely in Norway (14.3%) and France (39.9%) to very likely in Sweden (82.8%) and Germany (96.7%).

Whether in the United States or abroad, the total wages that service providers earn should have some bearing on whether or not they’re tipped. While the question of whether customers are being asked to subsidize the poor wages from employers is a fair one, it also might be moot because when employers are forced to pay higher wages, they often pass those increased costs on to customers in the form of higher prices.

So why not do away with tipping entirely and just pay more for restaurant meals, etc.? Theoretically, tipping provides value to customers because it allows them to adjust the amount they pay based on the quality of service they receive. Meanwhile, service providers have an incentive to do their jobs better, as they gain feedback about how well they’re performing. However, in reality, those benefits may not accrue for several reasons:

- Feelings of obligation: Even if service is very poor, patrons may feel obligated to offer an average tip, so they don’t seem cheap or unempathetic.

- Product prices: When customers believe they’re already paying a lot for something, they’ll sometimes scale back their tips – like the person who told me that while they typically tip for everything, they don’t always tip at Starbucks because they’re already paying $5.00 for a coffee.

- Poor timing: As suggested by my Chipotle example above, some companies ask for tips before the service has been completed. In those cases, your order may come out completely wrong, but you’ve already given a tip.

Despite several decades of work experience, I’ve never been in an occupation that received tips, which made me eager to hear from those who have. So, I reached out to two of my current students who have considerable food industry server experience.

Sarah Schall has worked in a variety of retail occupations, including as a counter-service food worker and as a waitress. She makes the important point that particularly in a sit-down restaurant, one’s overall dining experience is a function of many employees’ contributions, which should impact how patrons approach tipping:

“Although the waiter/waitress is the one who may seem to be in charge of a guest’s entire experience, it’s important to remember that there are many team members who go into creating a dining experience. Therefore, it wouldn’t be right to lower the tip that’s going to the server if the food took a while due to a slow kitchen staff.”

“If the food wasn’t up to par, or if it took a long time to get to the table, it most likely was the kitchen staff at fault rather than the waitress. Instead of leaving a poor tip, guests should inform the waiter/waitress that they were disappointed with their meal so that way the restaurant can improve and the server can work to reconcile the problem.”

Josh McCleaf grew up in the restaurant industry, working in a variety of front- and back-of-house positions in his family’s multigenerational restaurant. This experience has given him particular appreciation for the multifaceted and prolonged engagement servers have with customers in traditional dining:

“When you sit down at a table-service restaurant, you expect your server to spend the next 45 to 90 minutes getting you drinks, refills, meals, extra napkins, sides of ranch, and anything else you might need for your dining experience. It's also important to note that your server is not only fulfilling the needs of your table during your visit, they are also trying to fill the needs of every other table in their section at the same time.”

McCleaf contrasts this typical sit-down dining scenario with his own recent experience as a counter-service customer:

“A few weeks ago, I walked up to a Cinnabon stand in a mall to purchase two bottles of water. While the transaction was short and the water was only an arm's length away from the cashier, I was still faced with the increasingly popular iPad flip and a prompt asking me if I'd like to leave a tip. I have to admit that this put me in an odd position, and I was left to answer some questions: Was this one-minute interaction and simple order worthy of a 20% tip? Even if it wasn't, how bad would it look if I said no?”

McCleaf likens this incident to experiences patrons have at quick-service restaurants where interactions last for just three to five minutes and are “one and done,” i.e., people order, pay, receive their food, and leave, which is much different than the sustained engagement with servers in sit-down dining.

However, McCleaf emphasizes that even in these faster service restaurant formats, good customer service is vital, as servers who demonstrate dedication to their work, strong communication skills, enthusiasm, and patience may be well-deserving of tips. He concludes:

“What's important is that you tip at your own discretion. You should never be guilted into leaving a tip at these kinds of establishments.”

His admonition is a good one: guilt, fear, and other strong-handed emotional appeals represent coercion and aren’t appropriate for marketers to use. I’d add that organizations should be sensitive to how the tipping choices they offer, or don’t, can remove customers’ control and force their decision-making.

For instance, our family recently ate at a sit-down dining restaurant where when paying the bill, the lowest tip listed among the iPad’s preset choices was 20%. While I was happy to offer more than that amount, and I believe that servers deserve more for the hard work they do, it struck me as being too prescriptive – Why shouldn’t a patron be able to more easily offer any amount that reflects their satisfaction with the service they received?

To be true to its nature and intent, tipping must remain a discretionary thing – while it certainly should be encouraged, it shouldn’t be compelled.

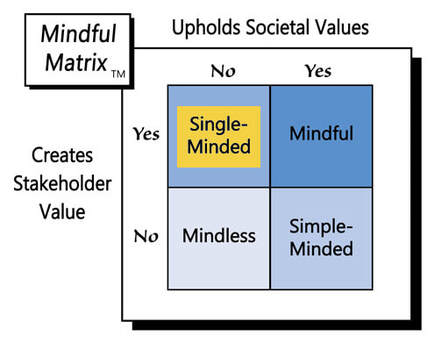

Anyone who has the ability to tip generously should do so, but ultimately, consumers deserve: 1) to decide without pressure how much they’d like to tip, 2) to make their choice, ideally, after they’ve received the service, and 3) to know, with some assurance, who will receive their gratuity. Discounting these ingredients for equitable tipping is a recipe for “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed