You’re probably aware of pharmaceutical company representatives whose job it is to persuade doctors to prescribe their firm’s drugs. You also may have heard of the generous gifts that some of those salespeople bestow on their clients: expensive entertainment, lavish trips, etc.

Many people have been concerned that such pretentious presents encourage doctors to do things they shouldn't, namely prescribe medication that’s not the best choice for their patients, simply because they feel obligated to reciprocate for the gifts they’ve received. Unfortunately, these fears are not unfounded, as an earlier JAMA study also found evidence that gifts may influence the specific drugs that physicians choose to prescribe.

Concern among industry stakeholders has led to reform of at least some of the worst practices. For instance, “drugmakers have tried to rein in some of the more lavish perks, like free golf trips and tickets to hot sporting events.” Likewise, a voluntary code by PhRMA, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, discourages drug reps from giving doctors vacation trips and tickets to theater and sporting events.

Even as expensive drug-related incentives have diminished, one practice remains prevalent—the giving of free food. “Drug-sales representatives routinely bring free food and beverages to doctors’ offices in an effort to get face time to promote their medicines. They also invite doctors to free dinners at restaurants to hear other doctors speak about certain drugs.”

Although some condemn any gifts that pharmaceutical reps might give doctors, others contend that something as minor as an inexpensive meal runs no risk of compromising a doctor’s professional opinion. The most recent JAMA study addressed this debate by comparing prescribing data from 279,669 physicians with 63,524 Medicare Part D payments from the Federal Open Payments Program in order to see if gifts given to doctors influenced their prescription practices.

Just as hypothesized, the study results revealed that physicians’ who received meals costing an average of $20 from pharmaceutical companies were more likely to prescribe those firms’ drugs than were physicians who received no such meals. Furthermore, the “receipt of meals costing more than $20 were associated with higher relative prescribing rates.”

Given these research results, can one conclude that cheap meals cause doctors to prescribe certain pharmaceutical companies’ drugs? Not necessarily. In JAMA’s own conclusion, it states “The findings represent an association, not a cause-and-effect relationship.” So, what’s the difference between causation and association, and does the difference really matter in this case? To answer those questions a simple example may help . . .

As many of us have observed, taller people tend to have larger feet. However, having large feet doesn’t cause one to be tall; rather, height and shoe size merely have a strong positive association, or correlation. What causes people to be tall are things like genetics and diet.

Similarly, drug companies’ cheap meals don’t necessarily cause the doctors to prescribe the drugs. Physicians are busy people, who might not have enough time to learn about all of the prescription drugs available for various conditions. Doctors do need to eat, though, so meetings involving a meal might work better for their schedules.

So, it may be during mealtimes that pharmaceutical reps provide information about their drugs that doctors don’t otherwise get. It’s likely the information, therefore, that really influences, or causes, the doctors’ prescriptions, not the meals. However, if the meals and the drug information are associated, and the information and prescriptions are associated, then the prescriptions and the meals will also have an association.

Besides the specific information that’s conveyed, meetings with salespeople are also about building relationships and establishing trust. Clients want to know that they’re dealing with a person and an organization that is reliable and that has integrity. They want to gain confidence that they’re dealing with a company that does things the right way and that if something goes wrong, the individual and the organization will be there for them and will make things right.

That type of confidence and trust is best built through in-person meetings. Yes, you can have those meetings without a meal, but something unique happens when you move a meeting from an office to a restaurant, or you otherwise break bread together. People tend to relax a little and interact more easily, making it possible to get to know others and their organization on a deeper level.

The preceding discussion is not meant to suggest, however, that all pharmaceutical reps are innocent of inordinate persuasion. If what some report is true, there are still representatives whose sales practices border on bribery. There’s never a place for that type of persuasion, which pits the self-interest of agents (e.g., doctors) against the best interests of their principals (e.g., patients).

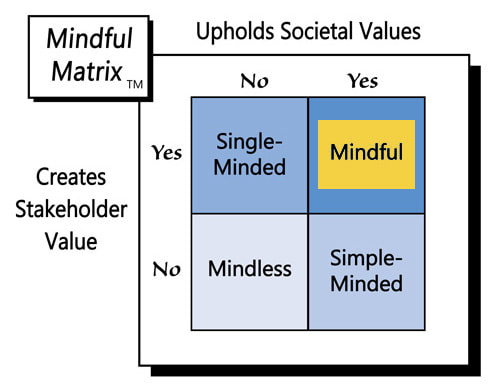

Still, it’s reasonable to contend that $20 lunches do little to convince doctors to compromise their professional opinions. Instead, the information they receive with the food is likely what’s influential. For these reasons, this marketing doctor's diagnosis is that cheap meals for physicians most often represent “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed