author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Market research apparently pegs football fans as key consumers of insurance, which would explain why televised games contain so many commercials for the likes of Liberty Mutual, Geico, and Progressive. One of the biggest buyers of advertising inventory has been State Farm, whose ubiquitous ads feature a couple of top National Football League (NFL) quarterbacks expressing gratitude for scoring special insurance deals.

In the ad campaign, Super Bowl champions Aaron Rodgers and Patrick Mahomes take turns conversing with casually-cool insurance agent, “Jake from State Farm,” who sports some stylish stubble, a snug-fit State Farm t-shirt, and the obligatory khaki pants.

The sports stars convey gratefulness to Jake for landing them 'exclusive' insurance deals. In one ad, Rodgers plays fetch with his dog while thanking the representative for giving him “the Rodgers rate” on his insurance, which Jake firmly denies:

“Here’s the deal. There’s no Rodgers rate. State Farm just has surprisingly great rates.” “We do offer it to anyone, literally anyone.”

Jake has practically the same conversation with Mahomes in a similar spot, as the two play corn hole. Like Rodgers, Mahomes thanks Jake for the “Patrick Price” on his insurance, but again, the agent resists:

“Here’s the deal, Patrick. State Farm offers everyone surprisingly great rates.”

At first glance, it seems like State Farm’s pricing play could work. In a celebrity-centered, influencer-driven world, people love to eat, drive, and wear what famous people do. So, why not add insurance to the list of endorser-inspired products?

The company’s ‘one-rate-for-all’ ads also could appeal to a value for of equality by suggesting that everyone should be able pay the same prices for the same products. Of course, charging people different prices would be unfair . . . or would it?

Legally, organizations can’t charge certain consumers more because of personal traits like gender and race. In terms of moral principles, it would be unfair to give more favorable treatment to some people and not others because of such characteristics. However, there are some legitimate reasons for price discrimination, for instance:

- Quantity Discount: People who purchase more deserve to pay lower unit prices, e.g., buying a six pack of soda versus a single can.

- Lower Risk: Individuals who objectively are less likely to default on credit terms should receive more favorable rates, e.g., a person with a very good credit score who puts a 50% down payment on a home versus another with a low credit score and 20% down.

- Buy Now: Because of the time value of money, as well as companies’ needs to maintain cash flow and reduce inventory, consumers often receive incentives for purchasing sooner rather than later.

- Peak Demand: Many people want to do the same activities at the same times, like going to the beach in the summer and to the movies in the evening, which is why hotels offer off-season rates and theaters have matinees.

There’s one other reason for price discrimination that’s not as clear cut—ability to pay. On one hand, companies shouldn’t be like the mechanic in National Lampoon’s Vacation: When Clark Griswold innocently asks him how much his car repair costs, the unscrupulous repairman boldly asks, “How much you got?” then demands “all of it, boy.”

On the other hand, it seems compassionate to charge specific consumer groups less because of their typically lower incomes, e.g., senior citizens.

In the industry in which I work, higher education, price discrimination is routine practice. Government and a variety of organizations collaborate with colleges and universities to offer tuition-lowering aid financial aid and scholarships, particularly to families with the greatest need.

That brings us back to Rodgers and Mahomes. Perhaps as spokesmen they receive State Farm insurance for free, but if they are paying something for it as the commercials suggest, these two multimillionaires certainly wouldn’t be getting a break on their rates because of inability to pay.

According to NFL.com, Mahomes’ $45 million a year salary is the league’s highest, and Rodger’s $33.5 million annual take is not far behind. Companies of all kinds strive to win the business of such high equity individuals, largely because they can afford full fare, i.e., they don’t require discounts.

Although you and I are less affluent, we understand that dynamic and wouldn’t want to pay the prices that Patrick and Aaron pay for anything. Hook us up, instead, with the rates their chauffeurs and gardeners are getting.

Of course, the commercials are meant to be funny, and we shouldn’t pretend we have the same buying power as NFL quarterbacks. Still, State Farm appears serious about uniform pricing by repeatedly suggesting that it offers “surprisingly great rates” to everyone without exceptions. That fixed pricing is the main flaw of the firm’s strategy; in fact, it’s a mistake from which one well-known retail chain is still struggling to recover, years later.

In November of 2011, JCPenney made a bold move in hiring as its new CEO former Apple retail executive Ron Johnson. In his effort to make JCPenney more Apple-esque, Johnson upgraded the stores' interiors and, more significantly, implemented Apple’s everyday ‘value’ pricing. If the no-sales strategy worked for the world’s most sought-after electronics brand, it should work for a clothing and housewares retailer, right?

Unfortunately for Johnson and JCPenney the strategy failed miserably. The firm’s revenue fell by almost $5 billion in one year and its operating loss grew to nearly $1 billion. Johnson was ousted from his job in March of 2013, just 14 months after he started.

The main failure in what some have called “the biggest retail disaster in history” was forgetting that people love sales. Many of us are captivated by the ‘thrill of the hunt,’ and we relish knowing that we got a great deal, whether it be versus regular prices or in comparison to what others have paid. I’m one of those people who is not above bragging about his consumer conquests.

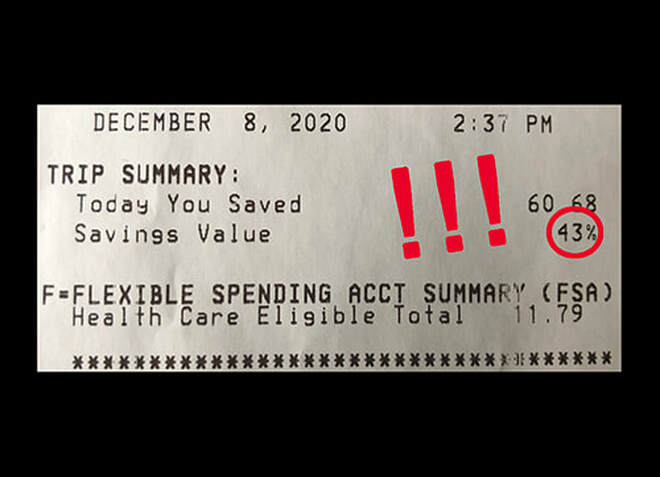

A few years ago when gas prices were on the rise, I shared a fill-up receipt with my wife so she could see how I paid a paltry $1.78 per gallon thanks to an abundance of grocery store reward points. Then, just this past week, I saved 43% on purchases at a drugstore chain thanks to various special discounts stacked atop a 30% off everything coupon. I hadn’t told anyone about that shopping feat, but I’m bragging about it now!

It’s not just me. Over the years, I’ve heard many others describe their exceptional purchases, a behavior I believe equity theory helps explain. As humans, we continually measure our inputs against their outcomes, including what we spend versus what we get for our money. We’re also constantly comparing our input/outcome ratios to those of others in order to gauge how well we’re doing at shopping or anything else.

Although usually effective, offering sales or running specials doesn’t work in every situation. For prestige products that command premium prices, like those of Apple, it can be counterproductive to offer frequent discounts, as doing so can diminish the brand’s perceived quality and cachet. However, in cases involving little or no product differentiation, businesses that ignore discounting often do so to their detriment.

Many insurance companies do offer discounts for things such as safe driving and bundling multiple policies (e.g., home and auto). In fact, State Farm is one of those firms; it offers a “Drive Safe and Save” discount of up to 30% on auto insurance. For some reason the company gives that program much less media exposure.

Aside from promoting or not promoting discounts, State Farm doesn’t help its cause by suggesting that all its customers pay the same rates whether they’re a multimillion-dollar quarterback or a more frugal football fan.

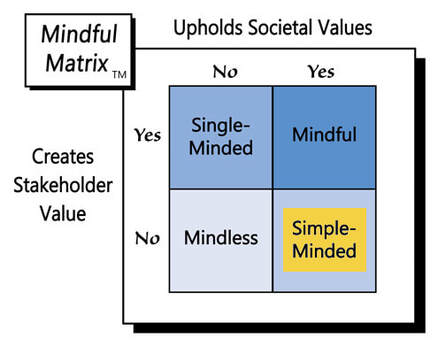

Price equality sounds nice, but there are legitimate reasons for charging people different prices, including allowing consumers to self-select and shop for prized discounts. At the end of the game, charging everyone the Rodgers rate really is “Simple-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed