author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

If you’re like most people, you’ve noticed a steady rise in reoccurring payments. Decades ago, monthly bills were restricted to things like rent and utilities, but they’ve since expanded to include regular charges for cellphone plans, movie streaming, and online news. And, the list keeps getting longer, as even more organizations find opportunities to automatically tap their consumers’ wallets for things like clothing (e.g., Stitch Fix), meal kits (e.g., HelloFresh), and shaving tools (e.g., Harry’s).

These examples aren’t particularly surprising—each day people wear clothes, eat food, and shave their bodies, so it makes sense to automate the purchase process and save consumers time shopping for such staples. However, subscription services for some other products should make any of us wonder, ‘Why?’

For example, BMW has begun to offer “heated seat subscriptions” in certain vehicles for $18 a month. According to James Vincent, writing for The Verge, “BMW has slowly been putting features behind subscriptions since 2020.” The automaker’s other reoccurring charges include automatic high beams and adaptive cruise control.

There’s also sneaker maker Cloudneo, which offers a “100% recyclable running shoe that’s only available by subscription.” For $29.99 a month, customers receive “an endless supply of shoes.” When pairs are past their useful lives, customers request new ones while returning their old ones, which the company grinds down and melts into plastic pellets used in its new product manufacturing.

These last two examples and several of those mentioned earlier are innovative approaches that reimagine marketing’s 4 Ps. All share strategic similarities as they fall under the subscription umbrella, but there also are significant and sometimes unsettling differences that make me want to better understand: When is subscription pricing right for both companies and consumers?

To answer this question, I turned to someone who has navigated the challenging process of transitioning his company’s signature product from a one-time purchase to a monthly subscription. Jason Kichline is founder and chief technology officer of OnSong, namesake of one of the world’s most widely used music performance apps. It allows musicians to digitally store, sort, and customize their music, saving them time and enabling them to focus on what they do best.

An annual guest speaker in my capstone marketing course, Kichline has told us of his firm’s deliberations about transitioning the OnSong app from a one-time Apple App Store purchase to a monthly subscription. OnSong started to offer a feature-enhanced, subscription version of its product a couple of years ago. This past June, OnSong finalized the monumental move by eliminating the one-time purchase option.

For many companies, the decision to go to full sail on a subscription model is simply a matter of what nets the most money, i.e., will more revenue from reoccurring payments offset sales not realized from potential customers who want a one-time purchase?

Although OnSong certainly considered income projections, it’s analysis was much more circumspect and other-oriented, which is evident as Kichline explains three main reasons for the move:

1. Relationships: “We’ve always placed a high value on supporting our users. A complex and full-featured app like OnSong demands a level of support that goes beyond that of a one-time purchase. A subscription creates the opportunity for a more formal relationship with users and the need to continually provide them with value. Our goal is to make our customers incredibly happy with the level of service, support, and features we offer.”

2. Continuity: “Although OnSong has been successful for more than 10 years, many software firms don’t last as long—they go out of business, or they’re acquired. A developer can keep an app around for a long time for some side money or an owner’s salary, but a buyer typically wants ROI. For this reason, new owners turn many one-time-purchase apps into subscriptions and try to ‘leverage’ the existing user base.”

“Even though app customers often assume they’ll be forced to upgrade to a subscription, we didn’t feel it was fair, so we grandfathered existing users.” Still, because going out of business also leaves customers stranded, we believe that subscribing to OnSong is the best path forward for all. A subscription to OnSong is an investment in the company and its product’s future.”

3. Value-Added: “The defining measure for most consumers is what they receive compared to what they pay. Although a subscription costs more than a one-time purchase over time, it also provides greater benefits, including important updates and improvements in an ever-changing technological environment. A cancelable subscription also reduces financial risk for consumers by allowing for product trial, which is often not possible with one-time software purchases.”

“Looking to the future, OnSong wants to provide a web-based version of the app that will store music and resources in the cloud, as well as manage bands and teams. A subscription model supports this additional functionality and added value.”

Kichline acknowledges that the transition to a subscription model has not been without challenges, which include effective communication with consumers, who can be swayed by public perceptions in social media.

Still, the change has been a good one for OnSong and its customers. After experiencing one “tight month,” the company’s revenues quickly rebounded to previous levels with continuing growth. That success should also be taken as a sign of the strength of OnSong’s value proposition in the eyes of consumers—the benefits they receive from the app are well-worth its reoccurring cost.

For Kichline, key to the whole process has been “having the mind of the consumer.” His analysis above and this summary statement make me ask: Do the subscriptions for BMW’s heated seats and Coudneo’s recyclable running shoes show an understanding of “the mind of the consumer” and a desire to truly meet customers’ needs?

Cloudneo’s product subscription may represent such a market orientation for certain hardcore runners who cycle through sneakers at a rapid clip. They might wear out a pair of running shoes every few months and could easily spend $360 or more per year on performance footwear.

BMW’s subscription is harder to justify. In his Verge article mentioned above, Vince raises good points that call into question the automaker’s motives:

“BMW owners already have all the necessary components [for the heated seats], but BMW has simply placed a software block on their functionality that buyers then have to pay to remove. For some software features that might lead to ongoing expenses for the carmaker (like automated traffic camera alerts, for example), charging a subscription seems more reasonable. But that’s not an issue for heated seats.”

When BMW manufactures vehicles with heated seats, it likely passes on the added material and labor costs to consumers at the time of purchase. So, the automaker is essentially holding back a feature for which customers have already paid so it can charge twice for what is an increasingly common new car addition. Such a motive certainly wouldn’t represent a customer-centric attitude.

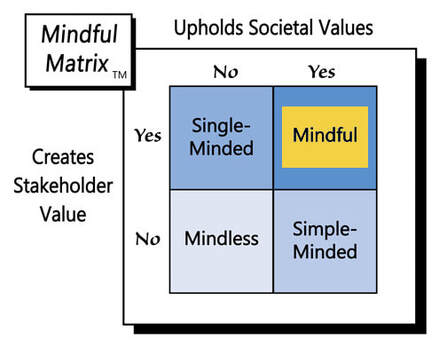

As BMW has shown, there are situations in which paying a reoccurring fee for a product makes little sense for consumers. However, when companies prioritize the three principles that Kichline has identified (relationships, continuity, and value-added), subscription pricing is “Mindful Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed