author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

It’s hard to think of inclusiveness of physical form without remembering Dove. Through its 2004 “Real Beauty” campaign the personal care brand pioneered promotion based on the reality that beautiful people come in all shapes and sizes.

Since then, many other organizations have mirrored Dove’s body-positive approach. Retailers like Kohl’s and Old Navy, routinely include plus-sized models in their ads, while Target and Macy’s employ variously proportioned mannequins to highlight similarly sized clothing.

Last month, the picture-lovers site Pinterest took body positivity a step further by announcing it would ban weight-loss ads. The social media platform explained that its decision was in the interest of individuals “facing challenges related to body image and mental health,” especially those suffering from eating disorders.

The first major social media platform to take such action, Pinterest’s unprecedented decision quickly received wide news coverage ranging from Fortune to NPR.

Most media cast Pinterest’s ban of weight loss ads in a positive light. For instance, an NBC News opinion piece called the choice “a glimmer of good news” amid more typically troubling stories.

It’s very encouraging that people increasingly recognize that everyone is different and that those differences can be celebrated. But are all differences good differences? Aren’t there certain behaviors that are objectively better for people to do, and others to avoid? Furthermore, are some marketers, like Pinterest, encouraging people to celebrate differences that could actually be harmful to them and to society?”

These are difficult questions to answer in any context, and they become especially tenuous when treating a topic like body image, which so directly impacts everyone, both in individual, psychological ways and in social, relational ways.

In my early years, I was a somewhat ‘chunky’ child and experienced, more than once, critical comments about my weight, which were hard to hear. As I grew older, taller and became more active, I lost weight, or maybe more accurately, didn’t gain much more. Ironically, I now sometimes receive unsolicited comments about being thin, which admittedly are easier to accept; although, they still make me feel uncomfortable.

Despite, this personal experience, a middle-aged man like me is probably not an ideal person to offer insights about body image and the social norms that surround it. When I feel ill-equipped to tackle an ethical issue on my own, which occurs often, I reach out to others who have different and frequently more informed perspectives.

In this instance, I needed as much help as ever, so I contacted several people who I knew would expand my perceptions by hearing their thoughts about Pinterest’s ad ban. Here are highlights from three interactions:

1. A veteran registered nurse, and Baby Boomer, who works in adult primary care as a nurse practitioner posed two important questions that also have been on my mind: 1) How effective are weight loss ads, and 2) “Do they promote healthy behaviors or unhealthy ones?” In answering both questions, she pointed me to a study published in npj Digital Medicine, which found that “online advertisements hold promise as a mechanism for changing population health behaviors.”

She also referenced CDC statistics that show that from 1999 to 2018, the prevalence of obesity in the United States increased from 30.5% to 42.4%. In her work, she sees firsthand how the effects of obesity, including diabetes and hypertension, can lead to “even more life changing complications.” She added:

“Weight loss is usually part of the treatment, and avoidance of obesity is usually preventative. So, if clicking on weight loss ads is a behavior that leads to seeking out more information on healthy behavioral change, then by all means, keep the ads.”

2. A member of Generation Y who works in the food marketing industry had a somewhat different take on weight loss ads. She said that her online scroll speed increases significantly in order to avoid the ads, which she says, “feel more personal as they poke at my self-esteem.” However, she qualifies her aversion to the ads, adding:

“I believe that weight loss products/services deserve to be advertised, but maybe in a way that’s sensitive to the cultural climate of body positivity/neutrality. I’m hopeful that these organizations could use that mindset as a framework guiding their ads, in a way that’s still effective at stopping someone’s scroll but acts as an invitation rather than a confrontation.”

3. A college student and member of Generation Z told me about his very significant weight loss: In just five months, this 6’ 3” young man lost 60 lbs., dropping from 260 to 200 lbs. Given that his accomplishment came mainly from “drinking plenty of water and exercising 4-5 times a week,” it’s not surprising that he emphasized the importance of approaching weight loss as a serious undertaking that requires perseverance:

“It is important to draw the connection between weight loss and hard work, the latter which must come first. It's about discipline, research, and taking your own personal initiative to develop an interest in personal fitness. You cannot simply buy a weight loss program and expect fat to magically remove itself from your body.”

Although he had no concern that society would suddenly become heavier if weight loss ads disappeared, he did express concern about any messaging that might normalize obesity:

“We will lose the idea of what is acceptable and what is not if we desensitize ourselves to what is normal. Being overweight is not a ‘normal’ state to be in, according to health professionals regardless of what ‘body-positivity experts’ have to say. It is common, but not healthy . . . It is ironic that the body-positivity movement promotes every body type more frequently than the ones deemed most healthy by scientists and health professionals.”

Of course, the opinions of these three people don’t represent the full spectrum of perspectives on weight loss and body image. They didn’t speak much to issues like anorexia and bulimia; however, I know each of them understands and empathizes with all who suffer from such eating disorders, as well as those who have been shamed because of their physique.

At the same time, these three voices have expressed important points that perhaps seem contrarian, probably because they tend not to receive the attention they deserve. For instance, they emphasized:

- The right type of weight-loss advertising, that’s affirming and realistic, can be effective and beneficial.

- Weight-loss is more a function of hard work and self-discipline than any quick fix.

- No one should be made to feel bad about their body, but normalizing obesity is not helpful.

- Although eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia are fairly common (1%-4% of the population suffers from them), obesity is much more prevalent: As mentioned above, in the U.S., 42.4% of adults were obese in 2018. Also, unfortunately, the pandemic has seen an increase in obesity, with an average weight gain of 29 lbs., making people more susceptible to the dangerous effects of the virus, as well as other serious illnesses.

It’s unfortunate that we live in a weight-obsessed society. Some marketers bear responsibility for helping to cultivate that preoccupation, e.g., by promoting unhealthy lifestyles that lead to excessive weight gain. Others are culpable for perpetuating unrealistic physical ideals and impossible ways of achieving them.

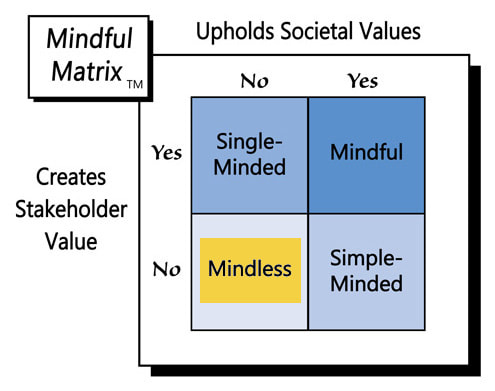

Pinterest is right to act against specific advertising abuses that cause others to feel shame and that encourage eating disorders. However, in embracing body positivity, the social media platform and others should be careful not to inadvertently endorse what is objectively one of world’s biggest problems, obesity, as doing so weighs in as “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed