author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

The company that found itself the focus of the humiliating headline was none other than Ernst & Young (EY)—one of the Big Four public accounting firms. The Security and Exchange Commission (S.E.C.) reported that between 2017 and 2021, hundreds of EY employees acted unfairly either by using an ill-gotten answer key for an ethics component of the CPA exam or by cheating on ethics tests required for continuing education.

As punishment for the systematic abuses, the S.E.C. fined EY $100 million, “the largest ever imposed by the Securities and Exchange Commission against a firm in the auditing business” and “twice the sum that KPMG, another big auditing firm, paid in 2019 to resolve an investigation into similar allegations of cheating by auditors on internal training exams.” That’s a significant sum; although, it's almost immaterial for a firm with global revenues of $40 billion in 2021.

What made EY’s, and KPMG’s, infractions all-the-more incredible is that they involved the firms’ auditing personnel—the very people who are supposed to ensure that the financial statements of the organizations they audit are accurate and truthful, i.e., that they aren’t cheating!

What would lead people reputed as among the most moral in one of the most ethical professions to make such a breach of integrity?

As one who hopes to help calibrate the moral compasses of the next generation of business leaders, this question hits close to home. Nearly 90 percent of the students in my undergraduate ethics course are accounting majors, and most look to land jobs in public accounting. In fact, some go on to work for Big Four firms.

Although I couldn’t say that these emerging accounting professionals are any more or less moral than those entering other fields, it’s important to note the common public perception that Gallup polls often capture: Accountants are among the most ethical professionals, having moral standards that are much higher than those in many other fields, including marketing.

All this to say, there are many reasons why I’d really like to understand how a moral breach of the magnitude of EY’s happens. Given that EY personnel likely would not want to comment on the case, I reached out to an expert in the field, who was willing to offer his perspective.

A professor of accounting and public accounting firm partner, Jim Krimmel taught auditing and other advanced accounting courses at Messiah University for more than 30 years, while employing the same best practices with his own firms’ clients. Krimmel is also certified in fraud examination and financial forensics, he’s served as an expert witness in accounting-related court cases, and he has conducted fraud workshops internationally.

As someone well-qualified to assess integrity in the field, Krimmel shared these thoughts about EY’s ethical violations:

“The story amazed me when I read it. If this was not so outrageous, it would almost be funny. The extent of the cheating, those who participated and those who let it continue, demonstrates to me a cultural problem in EY that is bigger than this issue.”

“That kind of culture, as with any firm culture, begins at the top. Somehow, those in authority ‘signaled’ that this behavior was acceptable. My concern now goes beyond this incident and makes me question the greater integrity of the firm. If we now begin to hear rationalization for this behavior, then that only increases my concern.”

“Corporate culture will be developed one way or another. If we don't purposely direct and develop it as leaders, then by default, it will develop poorly. This better be a wake-up-call for EY.”

Krimmel’s assessment was eye-opening for me. When moral infractions occur, we usually focus on the individual and their actions—what specifically did they do and why? Those are very important questions, but they can needlessly narrow the focus of analysis and risk overlooking systemic causes, i.e., broader influences on everyone taking similar actions.

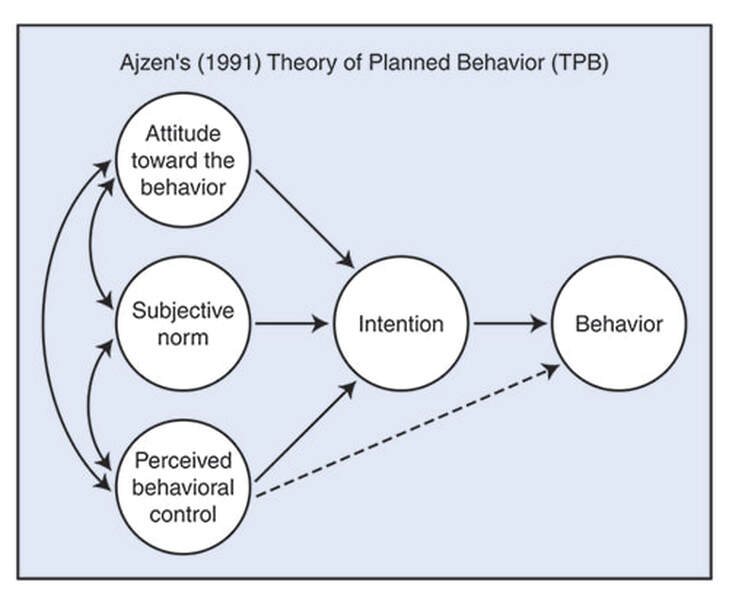

The complexity reminds me of a framework from social psychology I used in my dissertation research: The theory of planned behavior (TPB) suggests that people’s intended actions stem from three factors: 1) their own attitude toward the behavior (their thoughts and feelings about it), 2) their perceived control over the behavior (e.g., abilities and resources to do it), and 3) social influence on them (i.e., others encouraging or discouraging the behavior).

As members of a family, work team, or society, most of us want to be true to our personal beliefs and be accepted by others—Whether it’s the clothing we wear or things we say, we typically don’t want to look or sound so different that we disaffect the people we respect.

The “culture” Krimmel mentions exemplifies that need for acceptance and fits squarely in the third component of the TPB. As he suggests, company leaders bear special responsibility for shaping the cultures of the organizations they guide, for instance, by the policies they set, by the behaviors they celebrate or censure, and by their own actions.

It’s that last way that makes all of us moral leaders, regardless of any formal leadership title. We all ‘lead by example’ and constantly take cues from others for what to do or say in all kinds of social settings—I certainly do.

When I’m going out with my wife, I sometimes look to see what she’s wearing to gauge whether I should dress more formally or more casually. In a work meeting, I may look around the conference room table and decide to close my laptop if I see that others have closed theirs.

Those are easy, nonmoral choices. Ethical decisions are often more difficult and consequential, which likely makes social influence even more significant.

Imagine a newly hired staff accountant at EY who, among other things, is tasked with studying for and passing each part of the CPA exam so they can begin billing more hours. Chances are slim that the young associate would independently decide to risk their reputation and employment by cheating on part of the industry-standard certification, but if they know that others in their organization are taking such liberties and the company's culture endorses such abuse, they’ll be more likely to do the same.

Unfortunately for EY, there’s even more evidence to support that its culture has encouraged crookedness. A recent New York Times article described how consultants from the firm “devised an elaborate arrangement” to enable Perrigo, a leading pharmaceutical company, to dodge federal income taxes of over $100 million. When the original auditors from BDO balked at the setup, Perrigo moved its auditing to EY. The new EY auditors “blessed the transactions, which federal authorities now claim were shams.”

Regrettably over the years, plenty of other toxic company cultures have also precipitated major business scandals, e.g., Enron, Arthur Andersen, Lehman Brothers, Wells Fargo . . . the list goes on. Ousting an embattled CEO might make regulators and others feel better, but as Morgen Witzel maintains in writing for Mint, the bad business behavior usually stems from a much larger issue of rotten corporate culture:

“In many other cases, though, the seeds of failure stem from deep inside the company, its values and its culture. Those seeds sometimes lie dormant for years, even decades.”

Witzel acknowledges that fixing a corrupt corporate culture is a far-from-easy, long-term proposition. However, among several sensible suggestions, he offers organizations two critical challenges:

- View customer as “partners in value creation . . .with needs and wants that can be satisfied” and not as “cash cows to be milked in order to boost the earnings figures for the quarterly report”

- Have a “higher purpose connected with customer service and societal benefit” and don't exist “merely to make money”

Do people make poor moral decisions in the absence of social influence? Certainly; most of us probably have. However, it’s undoubtedly more likely that an individual will choose a wrong path if others they know encourage them to take it. Moreover, when a person is immersed in a culture that normalizes bad behavior, they might not even realize that what they’re doing is wrong.

To keep itself on the right path, some of the most important marketing any organization can do is internal marketing: ensuring that its own people’s vocational needs are met and with it, promoting a positive corporate culture that encourages ethical actions and condemns immoral ones.

Like many decisions we make, our ethical choices often occur with input from others, whether they realize it or not, which makes it all-the-more important for each of us to model morality everywhere, including in the organizations in which we serve.

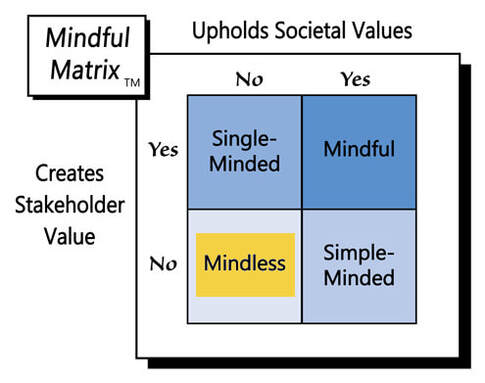

Companies should constantly evaluate how strongly their corporate cultures embrace ethical actions. Those whose embrace is weak will be like EY, ultimately hurting themselves and their stakeholders as they chart a path of “Mindless Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed