This year’s NCAA Division I college football season has culminated with a record number of bowl games. The first of 40 post-season contests kicked off on December 19, pitting Arizona against New Mexico in the New Mexico Bowl. The final bowl game takes place in Phoenix on January 2, when West Virginia plays Arizona State in the Cactus Bowl, a little more than a week before the National Championship game, which is not included in the bowl total.

To appreciate the rise to 40 games, it’s helpful to see the historic trend. In 1955 there were just six bowl games. Over the years, that number has steadily increased: to 11 games by 1975, 18 by 1995, 35 by the end of the Bowl Championship (BCS) era in 2013, and 40 by 2015. That’s an increase in bowl games of about 567% over 60 years.

Enabling more college football players to perform in the national spotlight is nice; however, the NCAA understandably also has more material motives, i.e., ticket sales and TV viewing. Fortunately fans turned out in mass for last season’s marquee matchups; for instance, 74,682 attended the Allstate Sugar Bowl and 91,322 packed into the Rose Bowl. Most other contests, however, drew much more modest numbers, as the average attendance of 44,365 per game suggests. Likewise, the attendance for returning bowls declined by 4%, and five bowls drew less than 25,000 people. The Bahamas Bowl had just over 13,000 attendees.

In keeping with ticket trends, television viewership of the premier bowl games also was very strong. In fact, the 2015 Sugar Bowl garnered 28.27 million viewers, making it “the second-most viewed telecast in cable TV history,” while the Rose Bowl, with 28.16 million viewers was not far behind. Such media deals represent a huge revenue source for college football and its member institutions; for example: “ESPN pays the College Football Playoff about $470 million a year for the media rights to the three playoff games and four other bowls and most of the money is distributed to the 10 FBS conferences and schools.” Still, seven of last season’s 39 bowl games attracted less than 2.1 million viewers, and 16 games garnered a household rating of less than 2.1.

In short, while top-tier bowl games are going gangbusters, lower level ones seem to be struggling, even as the NCAA adds more contests to the calendar. But, what could be wrong with more football, especially for college football fans? If a little football is good, more must be better. That logic holds until one looks at the post season proliferation both in terms of its quantity and quality. Holding 40 bowl games over a 15-day period amounts to 2.67 games per day. True, that average is lower than that of the regular college football season; however, bowl games should be different. In decades gone by these crowning contests were reserved for teams that truly distinguished themselves, earning the right to represent themselves and their conference by virtue of their outstanding winning ways.

Unfortunately, as of late, winning has become less of a prerequisite for earning a bowl bid. For instance, out of 80 teams playing in this year’s bowl games five have losing records: San Jose State, Georgia State, and Utah State ended their seasons with records of 6-7, while Nebraska and Minnesota finished at just 5-7. Furthermore, nine bowl-bound teams did only slightly better, posting records of 6-6: Connecticut, Washington, Indiana, Tulsa, Virginia Tech, Nevada, Auburn, Kansas State, and Arizona State. In sum, 14 of 80 bowl teams (over one-sixth, or 17.5%) compiled records at or below 500.

Given that there are 128 schools in the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) and that 80 teams (nearly two-thirds of the total) are needed to populate 40 different bowl games, it’s not surprising that the NCAA has had to reach deeper into the recesses of team rankings. In fact, just a few months ago teams with losing records could not have been considered for bowl bids; however, with one tweet, the NCAA amended its policy: “Without enough 6-6 teams, remaining bowl bids will be filled by 5-7 teams based on highest Academic Progress Rate.”

So, receiving a bowl bid has lost some of its luster, but why should the NCAA care when overall engagement is still strong? It should be concerned because oversaturation is often the first step in diluting a strong brand. Take McDonald’s. Granted, it’s challenges are multifaceted, but the restaurant chain’s longstanding emphasis on quantity (opening more and more stores) over quality (keeping its menu instep with consumers’ evolving tastes) has seen McDonald’s Interbrand ranking fall from sixth place to ninth place in five years.

In contrast, Apple has been a great guardian of its brand. Of course, the company operates very few of its own outlets, and it carefully chooses its retail partners. It also introduces a relatively small number of new products annually, each one laser-focused on boosting the Apple brand image: stylish and sophisticated, yet simple technology. For its efforts, Apple has earned much money and become the world’s most valuable brand.

As the NCAA continues to add bowl games with more teams of mediocre merit, Division I College Football bowl games run the risk of going the route of McDonald’s—too much quantity with questionable quality. In fact, it’s interesting to note that in Orlando alone, there were three bowl games this postseason: Capital One, Russell Athletic, and Cure—seems like McDonald’s-style saturation.

Instead, the NCAA should take pointers from Apple’s playbook, being careful to build rather than dilute some of the most prestigious names in all of sports: the Rose Bowl, the Sugar Bowl, the Orange Bowl, the Fiesta Bowl, which one might consider college football’s iPhones. More intentional branding and selective distribution would serve the NCAA well, much as it has Apple. Teams should not be rewarded just for “participation” in the regular season.

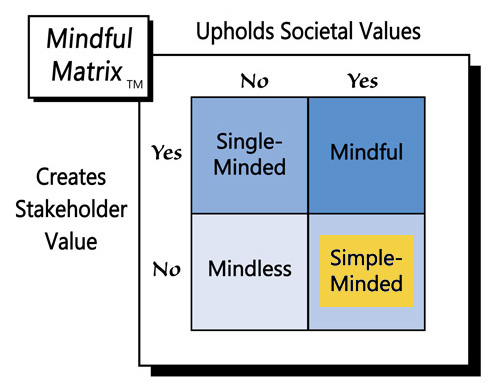

Branding everyone a winner may seem respectful to those who didn’t excel during the regular season, but the resulting dilution of college bowl brands will eventually erode stakeholder value. Consequently, the NCAA’s bowl game bloat signals a case of “Simple-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed