In the spots for his new sponsor, Marcarelli proclaims “it’s 2016 and every network is great.” Consequently, he suggests it’s not worth paying twice as much for a provider that’s only one percent better.

Someone recently asked me what I thought of Marcarelli’s less-than subtle shift to one of Verizon’s key competitors: “Is that ethical?” she wanted to know. To be honest, I didn’t have a good answer at the time. So, as I often do, I decided to give the issue more thought and write out my response, which is what you’re reading now.

First, it’s helpful to have a little context. Marcarelli is an actor, writer, and producer who has gained recognition for his roles in plays such as The Adding Machine and for his production of Bridezilla Strikes Back! Before the Verizon ads, he appeared in commercials for companies that included Dasani, Heineken, Merrill Lynch, Old Navy, and T-Mobile.

In 2002, Marcarelli began playing the part of the “test man” in Verizon commercials—a role he retained for nearly a decade. Even as recently as 2011, he appeared in an ad announcing Verizon’s release of the iPhone 4. Then, in April of 2011, the actor and the advertiser parted ways by mutual agreement, Verizon needing a new campaign and Marcarelli wanting to distance himself from the narrow image.

How, then, did Marcarelli end up as the spokesperson for one of Verizon’s main challengers? In a video interview, he responded to the question of why he changed carriers:

“Sprint asked if I would try the service, and if I liked it, if I would help spread the word, and so, so that’s why I made the switch.”

One of the first things people may wonder is if what Marcarelli has done is legal. Endorsement activities typically aren’t governed by statutes but by contracts between specific parties. As suggested above, Verizon and Marcarelli had a contract, which ended in 2011. Still, sometimes such work agreements contain clauses known as ‘covenants not to compete,’ which seek to prohibit employees from going to work for competitors when they leave their employers.

Even when such provisions exist, however, there’s no guarantee that courts will enforce them, especially if they’re deemed unreasonably restrictive. In any case, Marcarelli was probably not an employee of Verizon but a contractor, and it’s unlikely that his agreement contained such a provision. If it did, Verizon’s attorneys would be all over it, and Sprint’s commercials probably wouldn’t be airing.

So, Marcarelli’s shift to Sprint is likely legal, but that still doesn’t answer the question posed at the onset of this piece: “Is it ethical?” Just because something conforms with government’s laws doesn’t mean it upholds moral principles: State-sponsored genocide and legal segregation are two such unfortunate examples.

In terms of fairness, Verizon and Marcarelli apparently enjoyed mutually beneficial exchange throughout the time of their company-spokesperson relationship. Marcarelli played a key part in the company’s long-running ad campaign that saw Verizon Wireless’s domestic revenues rise from $19.3 billion in 2002 to $70.1 in 2011. Likewise, it’s reasonable to assume that Marcarelli was well-compensated for his promotional role, which required relatively little acting (“Can you hear me now”?), yet turned him into a national icon.

So, the two parties probably don’t owe each other anything more in a monetary sense. Each, though, does deserve from the other an extra measure of appreciation and respect—the kind afforded to individuals and organizations with whom we’ve shared a long-term, healthy relationship. That’s where Marcarelli may have missed the mark.

Even though his legal obligation to Verizon has ended, it’s ill-mannered for him to intentionally work against his former benefactor. “But,” you may be thinking, “Marcarelli’s occupation is acting, and he needs to ‘pay the bills,’ as we all do. To bar him from practicing his profession is like enforcing one of those overly-restrictive non-compete clauses mentioned above. It’s taking away his livelihood.”

This argument has some merit, so let’s compare it to another high-profile example of marketplace competition: LeBron James leaving the Miami Heat to return to the Cleveland Cavaliers. When James, or most other professional athletes, become free agents they inevitably end up playing for teams that compete with their former franchises. By winning the most recent NBA Championship, the Cavaliers denied the Heat, and every other NBA team, the same success.

However, an elite athlete like LeBron, in a very small industry like professional basketball, has no choice but to play for a competitor. Outside of the NBA, there are no opportunities at the same level. Contrast his situation to that of Marcarelli. There are thousands of other acting opportunities available that are as good or better than serving as a spokesperson for Sprint. There’s no reason Marcarelli couldn’t pursue one or more of those many other options.

Likewise, it’s important to wonder why Sprint would choose Marcarelli as the spokesman for its new campaign, especially when his persona was so long- and closely-associated with Verizon. Did Sprint have no other options, or was he was he the very best actor the firm could find? Probably not. Sprint knew that ads with Marcarelli would grab attention precisely because of the time and money Verizon had invested in developing their “test man” character.

As such, Sprint not only seeks to reap the benefits of something it has not sown, but it’s using those benefits again their creator. Some may argue, “That’s business.” Others, however, can rightly contend that Sprint’s approach is at least a little underhanded and represents something lower than clean and honorable competition.

Marcarelli, therefore, is susceptible to similar accusations for leveraging his national recognition to the detriment of the very organization that built it for him. Perhaps he’s not being disloyal, given that he and Verizon no longer have commitments to each other, but at a minimum his fast partnership with Sprint demonstrates a high degree of ingratitude to the organization that made him an icon. Whether Sprint is now the best value in wireless service is arguable, but that’s really not the issue.

So, an actor jumps ship from one telecommunications giant to another—what does it matter to all of us ordinary people who aren’t product spokespeople or CEOs? Well, many people take their social cues from advertising—one of our world’s most pervasive forms of communication. It makes a difference, therefore, when a large well-known company like Sprint suggests it’s okay to turn traitor or otherwise forsake the people who have helped make you who you are.

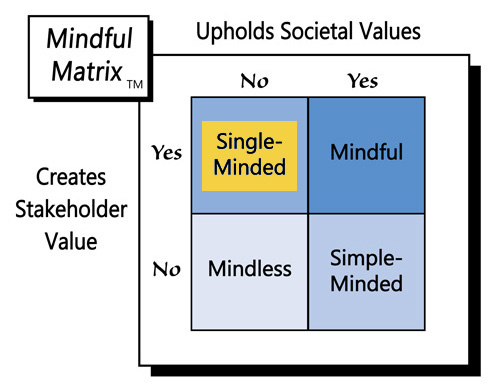

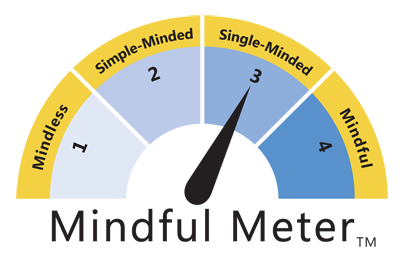

Yes, individuals and organizations change, and our attitudes toward them sometimes should as well. However, gratitude is a glue that in many ways holds our society together. So, although Sprint, Marcarelli, and many others may benefit from the new partnership, our value system takes the loss, which makes using a competitor’s spokesperson “Single-Minded Marketing.”

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix and Mindful Meter.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed