author of Honorable Influence - founder of Mindful Marketing

Discussions of ethics sometimes identify actions considered blatant wrongs, e.g., it’s never right to murder or rape. Other actions like lying and stealing elicit less unanimity, mainly because it’s possible to point to circumstances in which they might be okay, for instance:

- Lying to protect a friend from physical harm

- Stealing food to save starving family members

There probably always have been diverse perspectives about swearing; however, over the past several years, maybe because of social media or other factors, opinions about cursing appear to be coalescing: More people seem okay with the use of profane language.

One prominent recent example reflecting a broadening tolerance of curse words is the edgy slogan adopted by Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro: “Get sh_t done.” Shapiro certainly is not the first politician to employ profanity; although, his formalization of it as a political slogan is rather unique.

Politicians are far from the only professionals who have seen their vocabulary become more curse-word-inclusive. A 2016 study found that compared to other industries, healthcare workers used the most expletives. Also surprising, another study identified individuals in accounting, banking, and finance as the most foul-mouthed professionals.

Maybe the saying, ‘swears like a sailor’ will give way to ‘cusses like a comptroller.’

A 2023 study that surveyed 1,500 residents of the 30 largest metropolitan areas about their swearing habits found that respondents swore an average of 21 times a day, with men swearing more than women, Gen Zs swearing more than Baby Boomers, and people in Columbus, OH swearing more than those in any other U.S. city.

These studies and their statistics are eye-opening for me. I don’t encounter much swearing in my day-to-day, but I’m realizing that many other people do. From a recent personal experience, I also know the field of marketing isn’t immune.

I was meeting with a group of marketing professionals who wanted to create an attention-grabbing title for a coming event. As we brainstormed ideas, someone suggested a full-out profanity approach: “Get the f-ing most out of your marketing.” The suggestion, which was somewhat serious, received brief consideration from the group before dismissing it as too edgy and risky for branding.

So, it shouldn’t be surprising that a marketer would write an article asking when it is and isn’t okay to swear in an ad.

Over the years, I’ve taken a rather hard stance against the use of profanity in marketing, arguing back in 2017 that swearing can damage one’s personal brand and in 2021 that it can be harmful to others’ mental health.

Given the study statistics and findings referenced above and other signs of increased swearing, my hot take on the use of crude language hasn’t aged well! Still, I’m not ready to back down.

Like most people, I’ve said and written things that in retrospect I’d retract or reframe; however, those two articles aren’t among them. After rereading each piece, I believe their arguments are still sound, and I encourage others to read them.

I can't add a lot more to my case for countering cursing, but I would like to introduce one additional thought by asking a question:

What will be the cumulative effect of increased profanity and its ultimate impact?

To try to answer that question, a metaphor may help. A few years ago my wife and I decided to try eating more vegetables and less meat, which unexpectedly turned into vegetarianism. When people ask why I’ve chosen such a diet, I tell them that while I appreciate other reasons, the main one driving my eating behavior is sustainability.

From the documentaries I’ve watched and articles I’ve read, it’s very difficult for our world to support current levels of livestock and poultry production, and it’s impossible for our planet to provide a meat-centric diet to billions more people. Such a future is not sustainable.

Does one person eating black bean burgers instead of beef burgers make a difference? Not really, but it’s about offering a small contribution to the cumulative positive effect. An individual eating more vegetables and less meat alongside similar diets of millions or billions of other humans does make a difference and will produce a positive impact for our world.

I have to admit, suggesting that swearing is unsustainable sounds kind of silly at first. After all, all words, including curse words, are in infinite supply. However, projecting forward the trend of ever-increasing cursing, it's not hard to imagine some pretty unpalatable norms, for instance:

- Doctors and patients swearing at each other during healthcare visits

- Profane language becoming common at graduations, wedding ceremonies, and funeral services.

- Three and four-year-olds using the f-word in conversations with their parents and others

For some, a loss of decency and decorum may not matter. Some might even prefer a culture characterized by crudeness.

Others might rationalize that normalizing swear words would be a good thing because then they’d no longer be offensive. It is true that over time some words once considered bad, like “bloody” and “bugger,” stop being shunned, but new swear words always emerge. Moreover, there’s another potentially greater problem.

Individuals who suggest benefits of cursing tend to offer two basic arguments: 1) it helps the swearer in some way (e.g., by allowing them to off steam), and 2) it builds social bonds between the swearer and others (e.g., by showing their real self to others).

Perhaps there’s some truth to these arguments, but they probably only hold true if it’s swearing about something and not swearing at someone. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the first use easily leads to the second, and when people start cursing at others, situations rapidly degenerate.

Think of social media altercations, sports fights, and road rage. Most of us have probably heard or read of situations in which conflicts intensified then went off the rails after one person swore at another or otherwise flipped them off.

Are people capable of compartmentalizing their cursing and swearing about things that happen to them but not swear at others? Most people probably can. However, in a world that desperately needs to dial back both individual and organizational conflicts, is it worth the risk to further normalize the behavior?

Advertising is one of the world’s most pervasive and influential forms of communication. One ad with a single curse word won’t make much difference, but like one person eating less meat and more vegetables, it’s about the cumulative effect: If more and more advertising includes curse words, more people will follow suit, and some will not separate swearing about things from swearing at people.

In short, profanity-laced promotion is not sustainable.

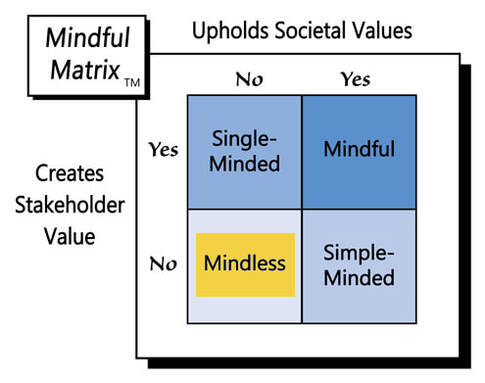

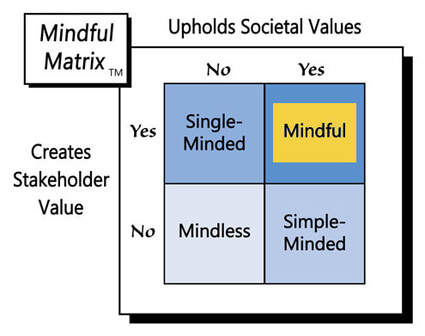

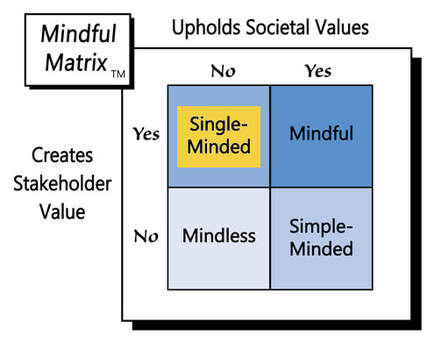

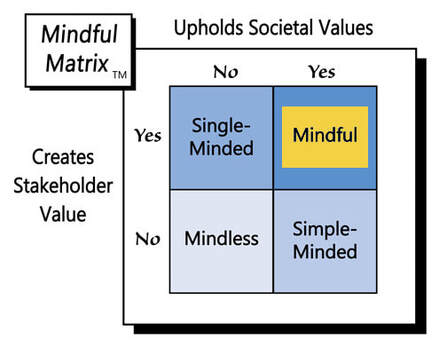

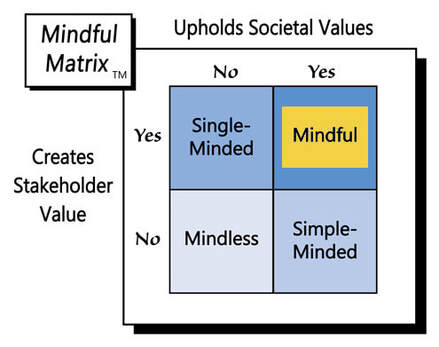

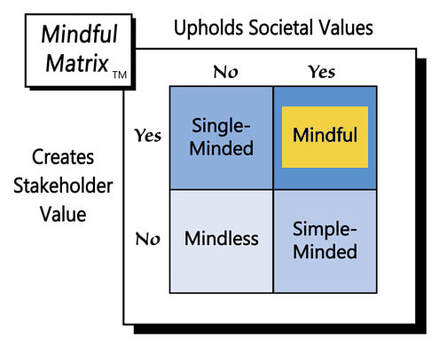

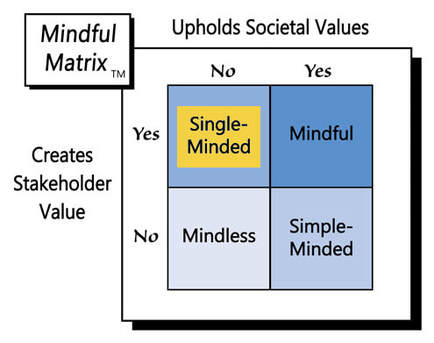

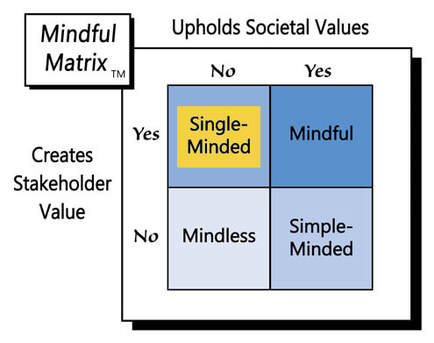

Those who work in advertising are some of the brightest and most creative people on the planet. Most are very capable of crafting engaging and effective strategies that don’t use swear words, which is why including profanity in ads is “Mindless Marketing.”

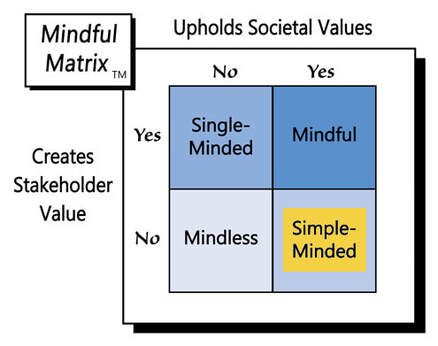

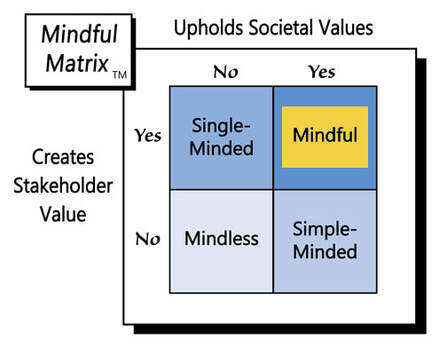

Learn more about the Mindful Matrix.

Check out Mindful Marketing Ads and Vote your Mind!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed